ADRIANA PROSER

John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art, Asia Society Museum, New York

ON FEBRUARY 10th, 2015, Asia Society Museum, New York, opened the first international loan exhibition focused on Myanmar (Burma) and its Buddhist heritage, with works from Myanmar and public and private collections in the United States. Comprising seventy objects, it is an unprecedented opportunity for the public to see and learn about the underexposed art of this recently reopened country. The fully illustrated catalogue, edited by exhibition curators Sylvia Fraser-Lu and Donald M. Stadtner, includes contributions by art historians, historians and religious studies specialists from the United States, Myanmar and Europe, and is sure to become an important resource for teachers, students and collectors of Buddhist art from Myanmar.

Buddhism has been a major force in Myanmar’s history for well over two thousand years. Various branches and sects of Buddhism informed elements of kingship and authority in Burma, as did Brahmanism, but this exhibition takes as its subject the Theravada tradition that today is a major part of the lives of eighty-nine per cent of Myanmar’s population. Theravada Buddhism, sometimes called “School of the Elders” or “Foundation Buddhism”, is an ancient orthodox school of Buddhism that stresses monaticism, the importance of the holy texts and meditation. Buddhist rituals, temple visits and pilgrimages have been a major part of the lives of much of Burma’s Theravada Buddhist population, including its rulers.

In order to achieve its aims, the exhibition includes works from the National Museum of Myanmar in Yangon and Naypyidaw, the Bagan (Pagan) Museum, the Kyauktaw Mahamuni Museum, Sri Ksetra Museum and Kaba Aye Buddhist Art Museum; and pieces from the Ackland Art Museum, Asia Society Museum, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, Center for Burma Studies at Northern Illinois University, Denison Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the New York Public Library, and the Southeast Asia Collection, Northern Illinois University Libraries, as well as two private collections in the United States. Through three exhibition sections, “The Image of the Buddha in Burma”, “Lives of the Buddha” and “Devotion and Ritual”, the exhibition explores the nature of Buddhist art and culture in Myanmar.

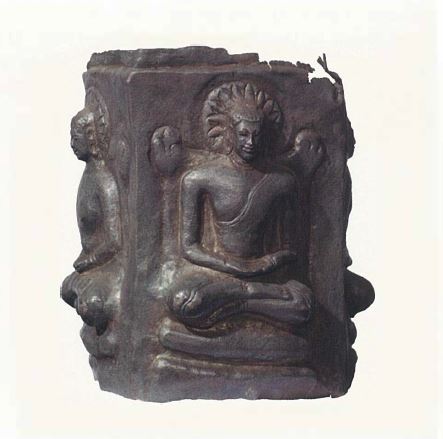

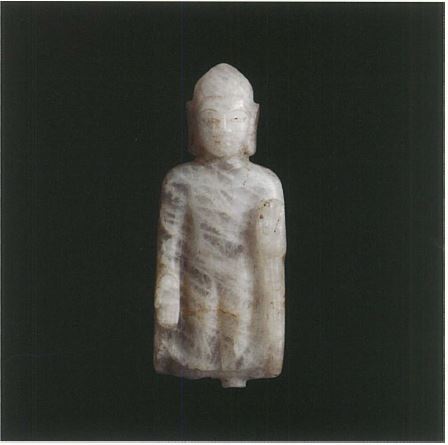

A multiplicity of styles found in Myanmar’s Buddhist images reflects the historical depth and geographical breadth of the country. The first section of the exhibition takes this phenomenon as its focal point. Two unique objects—one of sheet silver and the other quartz—in the exhibition can be dated to the Pyu period (1, 2), the time, as U Tun Aung Chain points out in his catalogue essay (p. 19), when urbanisation in Myanmar began. By the 7th to 9th centuries when these two works were produced, the Pyu, early inhabitants of Central Myanmar, had conducted significant trade with the Indian subcontinent. The impact of these trade relations is revealed in the stylistic debt the objects owe to the Buddhist art of India’s Gupta period. The four-sided sheet silver object with a repoussé image of a seated Buddha on each side (1) may be what is left of a component of a reliquary. It numbers among the pieces that emerged from the Khin Ba Stupa relic chamber when Charles Duroiselle conducted excavations at Sri Ksetra in 1926–1927. The figures of Buddha on the object show no differing iconographic features and each is seated on the same kind of throne, but they may represent Konagamana, Kakusandha, Kassapa and Gotama (Fraser-Lu and Stadtner, p. 47). The skin-tight robes are a hallmark of the Gupta period.

This same feature is shared by a small, but exquisite, standing Buddha image carved of translucent quartz with white occlusions, and discovered in 2005 within the walled city of Sri Ksetra (2). A craftsman created the piece lovingly, simply carving the fine features of the Buddha’s sweet face. It is the only quartz Buddha of a significant scale that can be associated with Myanmar in the second millennium.

While the Pyu Buddha images show elements of Gupta cross-fertilisation, Bagan period works point to relations with Pala period India and a familiarity of the style of work created for Bodhgaya and its surrounding area. A standstone sculpture of the Buddha seated in dharmacakra mudra (3) is a quintessential Bagan period piece with a clear debt to the Pala stylistic conventions. A formal relationship between Theravada Buddhism and the Burmese government began in the Bagan period (800–1300). During this important period of development for Buddhist Myanmar, King Aniruddha, who ruled during the second half of the 11th century, integrated religion and state. As a result of this formalised relationship, Theravada Buddhism became reliant on state support of the preservation of the Buddhist monastic community (Sangha) and the system of religious donations. The Kingdom of Bagan’s familiarity with the sculpture of Bodhgaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment, was aided by the religious missions they periodically sent there (Aung-Thwin and Aung-Thwin, p. 99).

These stylistic qualities also feature in a magnificent carving of the Birth of the Buddha created for Kubyauknge Temple in Myinkaba village (4). In this sculpture, the primary focus is Queen Maya, as she grasps the branch of a flowering tree with her right hand and is supported by her sister, Prajapati, as the infant emerges from her right hip. Four events related to the Buddha’s birth are representationally referenced to the left of the composition. The fastidious detail of the elaborate headdresses, bracelets, necklaces and girdles, as well as the scale of larger and smaller figures, indicate the stylistic influence of the Indian Pala period, while elements like the comparatively rounded faces and stockiness of the figures show the hand of Myanmar sculptors.

International trade and relations, local Buddhist practice, and the relationship between government and Buddhism contributed to the unique combination of style, technique and religious icons that appear in the arts of Buddhist Myanmar. While Bagan period works in the exhibition show strong Indian Pala period Buddhist influence, Ava period (1287–1782) sculptures show the strong development of local styles. A lacquered and gilt wooden sculpture of a Buddha, seated erectly on three charmingly ornamented elephants (gajasana) (5), looks downward. His proportionately large head gives the figure a child-like quality often exhibited in Buddha figures of this period. Viewed from the side, the elephants seem to come alive with grace and a sense of movement. Another 18th century Buddha (6), seated on a squat I-shaped royal throne, also has similar proportional qualities as well as spatula-shaped hands. However, this provincial piece wears a fabulous crown with wing-like appendages and big ear ornaments. His nose and eyes are broader and not as finely crafted as in the former example. Crowned images within Burma’s Theravada tradition likely represent a local king perceived as Maitreya, a future Buddha. Myanmar’s people were conscious of the predictions in their doctrine of a future time when the world would be peaceful, the kingdom powerful, the Sangha pure and the people righteous.

During the Konbaung dynasty (1752–1885), another dramatic shift in style occurred in Myanmar. This was a period when Myanmar’s rulers extended their domain into parts of Laos and Thailand (Siam), and the influence of Thai craftsmen is evident in a resplendent gilded and inlaid lacquer Buddhist sculpture (7), which possesses an elegantly elongated body and lovely oval face with a tall forehead; also seen in Thai Buddhas of this period, the lively flowing drapery of the Buddha’s robes combine with these aforementioned features in what has become known as the classic Mandalay style. This tendency toward elongation of the body survives into the British period, as is exemplified by a dry lacquer crowned Buddha dressed in courtly garb that owes much to that worn by Thai rulers of the period, although the sculpture was likely created in Myanmar’s Shan State (8).

In Myanmar’s Buddhist practice, the belief in karma is particularly emphasised. Myanmar’s Buddhist kings, particularly from the Bagan period on, believed in a meritorious path to …

Click here to access Arts of Asia‘s March–April 2015 issue for the full article.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift