CLARISSA VON SPEE

Chair of Asian Art and Curator of Chinese Art, Cleveland Museum of Art

THE CLEVELAND Museum of Art (CMA) opened its doors to the public over a century ago, in 1916. Since then, the museum’s collections have been free of admission and “for the benefit of all the people forever”. Cleveland was at the time one of the nation’s largest and wealthiest cities, with a diverse community including a high percentage of immigrants and industrial workers. The museum’s trustees wanted the institution to be “a live educational force in the community” and were convinced that this goal could only be achieved by collecting “the best objects in all branches of art”.

However, the CMA’s encyclopedic collection of artworks is not only known for rarity and exquisite quality, but the arts of India, China, Japan and Korea were a main focus of interest from the museum’s inception. In fact, the museum’s first curator, Arthur MacLean, had been trained in the Oriental Department at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. MacLean’s appointment was announced in the Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1914 as follows: “It is hoped that his [MacLean’s] enthusiasm and his knowledge of Eastern art will so stimulate interest in the art of the Near and Far East in Cleveland that his whole attention may, before long, be required for the care of a department of Oriental Art in the Museum”. Today, the Asian collections, especially the Chinese holdings, have works of art in almost all media, with particular strength in Buddhist sculpture, classical Chinese painting, Chinese ceramics and silk textiles. Among these four groups, the CMA’s magnificent collection of Chinese silks has received little attention. The museum’s overall strength in textiles, however, reflects its founders’ endeavour that “Cleveland—with its important clothing and weaving industries—should have the advantage of a splendid collection of textiles [ … ] “.

Dating from the 8th century to modern times and covering a large geographical area from Central Asia along the trade routes of the Silk Road to the imperial silk weaving centres in south-east China, these textiles are noteworthy for their high quality, pristine condition, and breadth in silk weaving types, manufacturing techniques and ultimate usage. In 1997, the CMA and The Metropolitan Museum of Art jointly organised the splendid exhibition, “When Silk was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles”, presenting to the public exemplars from two of the most important Chinese and Central Asian textile collections outside Asia.

This year, the CMA presents a selection of its highlights in a new gallery display, titled “The Splendor of Chinese Textiles: From the Silk Road to the Imperial Court” (February 8th to August 12th, 2018). The earliest dated textile on display is an 8th century coat, presumably made for a young Tibetan prince (1). A major and fairly recent acquisition, much has been written about this spectacular textile, which was acquired together with a pair of trousers. The outer fabric of the coat, a silk samite (weft-faced compound twill) woven in five brilliant colours and featuring paired ducks in pearl roundels, bears all the hallmarks of tile precious and highly desired silks from Sogdia (present-day Uzbekistan) or Eastern Iran. The coat’s inner lining is a twill damask with a floral pattern made in China. The same fabric was used to line the accompanying pants (not on display), suggesting that both garments originally belonged together. A pair of small boots, made of the same outer fabric as the CMA coat, is in the collection of the Hirayama Ikyu Silk Road Museum in Japan and complements the set. Given the coat’s pristine condition, it is not clear whether the garment was ever worn or whether it served as a diplomatic gift or perhaps as currency. The combination of Sogdian and Chinese silks in one garment is evidence for the vital exchange and cultural interaction amongst the peoples living along the Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting China with Central Asia and the Middle East. With its provenance from Tibet, it seems probable that the costly garment reflects the immense power of the 8th century Tibetan empire, which then controlled parts of Sichuan, Qinghai and Xinjiang provinces, including the Gansu corridor. The Tibetan King Khri-Idegtsug-brtsan (704–754) had even sought marriage alliances with princesses from both China and the Sogdian city state of Samarkand.

The constant change of power constellations among the peoples from north and north-west of China throughout the following centuries is reflected in the production and exchange of textiles and motifs from this region. The occupation of Chinese territory by northern invaders from the steppe lands often resulted in the relocation of parts of the native Chinese population. The Khitan, Jurchen and Mongols all forced captive Chinese artisans, including weavers, to move from their homeland and settle in locations or centres with foreign artisan activity. In addition to trade, migration and pilgrimage, the relocation of artisans thus fostered the transmission, exchange and the merging of indigenous and foreign motifs and weaving skills.

Also on display at the CMA is a pair of Liao dynasty (907–1125) boots, made of finely woven silk tapestry (kesi), featuring two phoenix in flight chasing a flaming pearl (2). Although the bright colours of the fabric have become muted through burial and the gold threads are partly disintegrated, the once lavish use of gold and the Chinese inspired phoenix motif suggest that the boots were made for a member of the Liao imperial family, most probably a woman. It is worth noting that at the time the Liao boots were produced in Khitan-occupied northern China, footbinding began to become customary among upper-class women in southern China. The high value the Khitan accorded to boots relates to their mobile, semi-nomadic lifestyle. Moreover, the exchange of leather boots between the Song (960–1279) and Liao emperors is recorded in an 11th century text. Boots made of silk tapestry were models for bronze and silver-gilt boots found in Liao tombs. A pair of silver gilt boots (dated 1018 or earlier) with phoenix motifs and cloud scrolls, closely resembling the CMA textile pair, was excavated from the tomb of Princess Chen and Xiao Shaoju at Qinglongshan town in Naiman Banner. The motif of magnificently long-tailed phoenix with cloud scrolls can also be seen on a large contemporary bronze mirror (3). While the mirror, inscribed by its maker in Jinling (Nanjing), was produced in the south-east, the boots were made in the northern part of China then occupied by the Khitan.

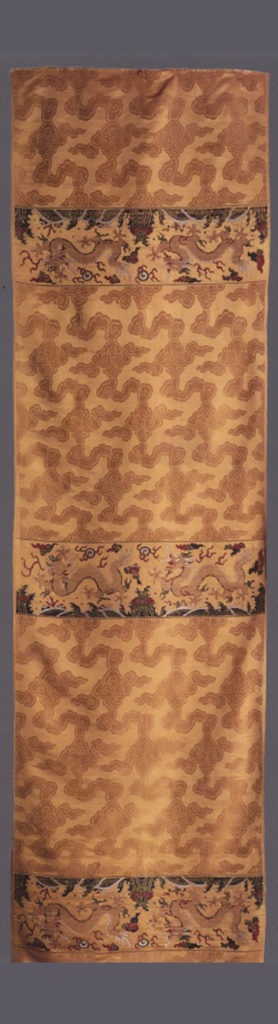

Textiles played an important role in Chinese diplomacy with foreign states and at court. Bolts of silk served as diplomatic gifts to pacify border populations and to maintain balanced power constellations. During the Song dynasty, the Chinese court agreed to pay annual tribute to the Liao-Khitan in the form of thousands of silver taels and bolts of silk. The treaty was followed by comparable arrangements with the Xixia and Jin peoples. Over centuries the Chinese court endeavoured, with varying degrees of success, to keep a stable relationship with powerful Tibetan Buddhists. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), in particular under the Yongle emperor (reigned 1402–1424) who was a devout Buddhist, vast quantities of gifts of all kinds were sent to Tibetan monasteries or were received by political dignitaries. Later, the Shunzhi emperor (reigned 1644–1661) invited the Fifth Dalai Lama to Beijing in 1652, and in 1779, the Sixth Panchen Lama visited China at the request of the Qianlong emperor (reigned 1736–1795). Qianlong recognised the supremacy of the religious authority of the Dalai Lama, and in turn the Tibetans acknowledged the Qing emperor as an incarnation of Mañjuśrī, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. A striking painting that depicts Qianlong as Mañjuśrī in the Palace Museum, Beijing, documents this acknowledgment. During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the Chinese court began to send gifts of court garments and furnishings to Tibet where they were altered to Tibetan-style narrow sleeve robes with close fitted neck and a distinctive overlap in the front, called chuba. A magnificent 17th century robe in the CMA collection, made of Chinese silk satin for a Tibetan lama or an aristocrat, prominently documents the complex relationship maintained between powerful Tibetan Buddhists and the Chinese court (4). The CMA chuba has been fashioned from a sumptuous imperial satin wall hanging. John Vollmer, who studied the piece, concluded that Tibetan tailors cut it into sixty separate units, reassembling the fabric to a completely new, dramatic and bold design. The wearer of such a garment must have impressed bystanders by his striking appearance.

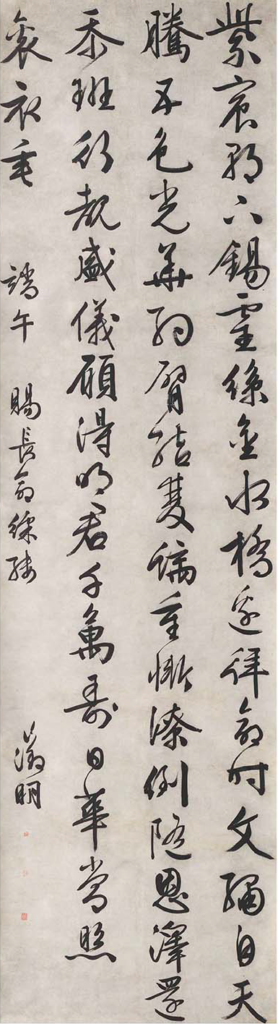

In addition to foreign dignitaries, court officials benefitted from imperial gifts made of Chinese silk. A poem by Wen Zhengming (1470–1559), in running script style calligraphy in a hanging scroll format in the CMA, expresses Wen’s gratitude to the Jiajing emperor (reigned 1521–1566) for a gift of an embroidered silk given to him in appreciation of his meritorious service (5). The poem reads:

As I expressed my gratitude to His Majesty by the Goldwater Bridge.

This heavenly silk is embroidered with five colours. Resplendent it is, draping over with my arm [designs of] twin dragons.

Having received such a gift, I [bowed] in shame over my lack of achievements.

Humbly I returned to my rank to observe the grand ceremony I wish His Majesty shall live on far myriad years, And the sun will always shine upon His trailing robe.

Since the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) the production of silk for imperial use increasingly concentrated in the Jiangnan region, the Lower Yangzi (Yangtse) Delta. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the main official imperial workshops were situated in Hangzhou, Suzhou, Nanjing and Beijing. Tax payments, largely in the form of rice and bolts of silk, were submitted and shipped from the Jiangnan region to the capital (6).

Due to the warm and humid climate in China’s southeast, local silk workshops specialised and excelled in the making of airy, semi-transparent gauze garments that became fashionable among women and men. A recently acquired painting in the CMA collection shows a woman in such a dress of semi-transparent red gauze (7). The painting relates to the legendary love story between Tang dynasty (618–906) Emperor Xuanzong and his consort, the beautiful Yang Guifei. Set in a contemporary 18th century southern interior, Yang’s nude body can be seen through the red robe as she leaves the bath.

Raising silkworms, weaving and embroidering silk were primarily the domains of women. Some excelled in this pursuit to a degree that they gained the recognition of the emperor. As a result, their woven tapestries or silk embroideries were …

Click here to access Arts of Asia‘s May–June 2018 issue for the full article.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift