JOHN CLARKE

Curator of Himalayan and South East Asian Art, Victoria and Albert Museum

THE COLLECTION of lacquer objects from Burma (Myanmar) held by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), though not numerically large, is nevertheless important, as it documents in a representative way lacquer production during the 19th and the early 20th century. This encompasses much of the British colonial period, from the time of the Second Anglo Burmese War (1852–1853) through the final British annexation at the fall of Mandalay in 1885 to approximately the start of the Second World War (1939). Good, and sometimes exceptionally fine, examples of the main types of vessel and other characteristic objects exist for this period. A significant number of these were shown in the various exhibitions displaying art from across the British Empire that followed the huge success of the 1851 Great Exhibition. These included the Indian and Colonial Exhibition of 1886, the 1902 Indian Art Exhibition at Delhi and the 1924 British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. The significance of many of these pieces is enhanced because numbers of them are approximately dateable. This is due to the history of the V&A (then the South Kensington Museum) and the fact that it inherited the East India Company Museum’s collections in 1879, together with that museum’s registers. The recurrence of the acquisition dates, 1855 and 1867, in the original registers, or “slip books”, from the East India Company Museum strongly suggests that pieces were acquired after being displayed at the Paris Exposition Universelles of 1855 and 1867 respectively.

The V&A also contains several extremely rare lacquer masterpieces, most notably the Buddha shrine from the Mandalay Palace (see below). Lastly, the museum holds the best collection of carved and lacquered furniture outside of Myanmar.

The use of lacquer in Myanmar, though originating in China, almost certainly came via one or more of the several neighbouring states, where it had been used from an early period. Perhaps the most significant areas in this respect are Yunnan and Sichuan, with which Burma has had regular contact throughout its history. One of the indigenous peoples of Yunnan, the Po, formed part of the population of the Nanchao kingdom (8th to 13th centuries) who were renowned for their beautiful lacquer. The Yi people of south-west Sidman also have a 1700 year history of lacquer production, which continues to the present day. One early account that may refer to the use of lacquer in Myanmar is tantalising, but not conclusive. Based on the visits of envoys, the Chinese annals record that the Pyu (6th to 9th century), an early civilisation based in central Myanmar, had “over a hundred Buddhist monasteries with courts and rooms all decked with gold and silver, coated with cinnabar and bright colours, smeared with kino and covered with embroidered rugs”. The reference may refer to the use of red (cinnabar tinted) and other hued lacquer; however, even if this was not lacquer as we know it, it implies the use of tree resins as a decorative finish.

The first evidence of the use of lacquer, however, has been provided by excavations at the Laymyethna temple in Pagan (Bagan). There, the bases and fragments of five lacquer-coated basketry cups, dated by a foundation inscription to the first quarter of the 13th century, have been recovered. This augments the known use of red lacquer to coat wooden Buddha sculptures from the same Pagan period and the report of the finding of a lacquerwork box dated to 1274 in the Mingala-zeidi stupa in 1919. Unfortunately, the box is now lost. In the early 17th century, Burmese armies again attacked the region of Chiangmai in today’s northern Thailand, which they had subjugated in 1557. One result of this second military action was the forcible resettlement of 40,000 artisans, including lacquer craftsmen, from the area to Burma. Living close to Chiangmai were the Yun or Lao Shan tribe, who were renowned for their skills in producing lacquerware. An attack on the Thai capital of Ayutthaya in 1767, which destroyed it, brought a final influx of craftsmen, and so the techniques may have come from either, or more probably both, regions. The link to the Yun of Chiangmai is, however, commemorated in the traditional Burmese term “yun ware”, which refers to a technique of engraving lacquer that became characteristic of Pagan in central Burma.

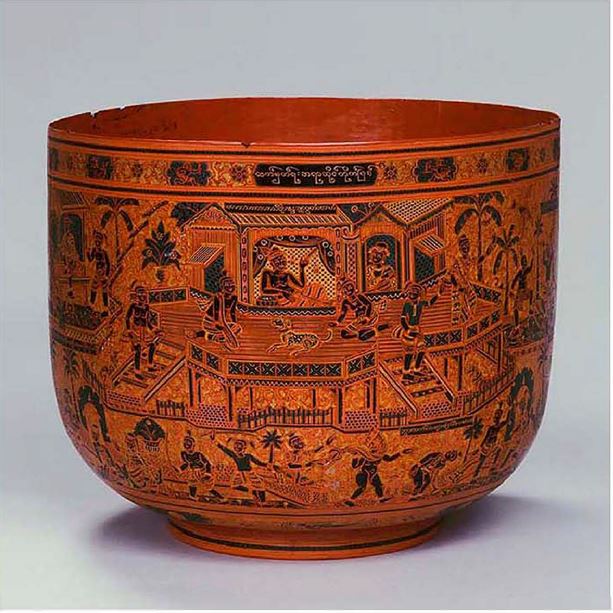

The yun ware bowl (1) beautifully exemplifies the yun technique of fine engraving employed to decorate the final polished layer of the vessel. The initial stage of its construction would, however, have closely followed a traditional set of processes used for all vessels. Like almost all lacquer containers, the body is formed of split and woven bamboo. In this case, to increase flexibility but retain strength, horsehair has been interwoven as weft between the warp of thin bamboo strips. The use of horsehair in this manner is a late 19th century development, and does not occur earlier. Like most of the process described here, it continues to be used today. Once completed a woven body is infilled with a low grade lacquer mixed with clay, then smoothed vessels are dried slowly in an underground storeroom with high humidity to prevent cracking. Successive layers of better quality lacquer mixed with finer and finer fillers are then applied. The next layer after the first coarse filler, for example, is mixed with the ash of burnt teak sawdust, and the succeeding with burnt cow-dung ash or bone ash. After each coat, the piece is smoothed and dried, between twelve and twenty-four layers being usual, although especially finely made containers might receive additional coatings. After a final polishing with agate or fossil wood, a design is engraved onto the surface with a metal stylus and colour applied to the incisions. Dry smoothing removes the excess colour and this first set of coloured designs is then sealed using the resin from the neem or acacia tree. The same process is repeated with another set of engraved incisions made for the next colour, with four to five colours being typical. When finished, the entire decoration is sealed with lacquer mixed with tung oil. The whole process, including all the drying and coating stages, can take from four to eight months to complete.

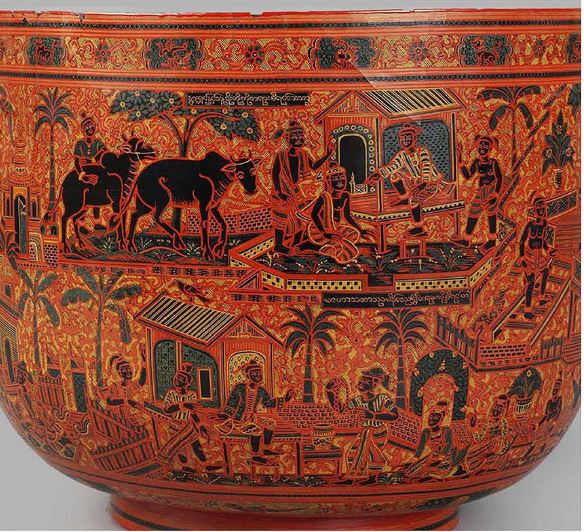

Most raw lacquer, called thit-si in Burma, comes from the Shan States and the Kathe and Barno districts in the eastern and northern parts of the country. It is sap harvested from the Melanorrhoea usitata tree, which is tapped by making V-shaped incisions in the bark. This grey liquid turns black as it is exposed to the air, and black is the most typical colour of vessels from Burma. The yun bowl (1) has, however, been made from an attractive rich red lacquer called hinthabada, created by adding mercuric sulphide. Other parts of the design are in green, yellow and black. The main decoration is that of the nan-dwin, or “King at Court”, design where the figures are set in a stylised palace. The actual stories are drawn from one for the previous lives for the Buddha, the Mahodatta Jātaka, recounting the Buddha when he was a wise judge (Story of the Wise Young Judge). For example, he is shown giving judgment on the ownership of a cow between the owner and a thief (2).

In cartouches around the top, the signs of the zodiac (ya-thi) are shown, a favourite auspicious Burmese theme. One cartouche names the master craftsman who made the bowl, saying, “From the workshops of the prize-winning crafts-master Saya Saing; guaranteed genuine horse-hair woven lacquer bowl; prize winning certificates can be produced for inspection”. The practice of craftsmen signing their work was a new development that followed Burma becoming a province of British India in 1886, and was linked to the introduction of craft exhibitions and especially competitions, both local and international, which occurred a number of times during the British period. For competitions, craftsmen produced their best work and often listed their names on the underside or around the rim, as here. This piece was almost certainly new when purchased by the donor from an annual exhibition of arts and crafts in Rangoon (Yangon) during the period 1908–1911, and probably dates from shortly before that.

The qualities of lacquer are often said to resemble those of plastic, giving people of former ages many of the same advantages of the modern medium, especially in terms of its flexibility and lightness, together with its hygienic and waterproof properties. Lacquer was used by all levels of society for containing food, liquids, jewellery, ornaments and other items.

One of the most ubiquitous forms was the cylindrical box, or kun-it, used to contain the ingredients of betel or pickled tea (illustration 3 is a black yun ware box containing a nest of five others and one tray). As one box fits within the other, in the manner of Russian dolls, it is not immediately obvious how the ensemble was originally used. Betel boxes more often contain trays with small containers to hold the ingredients. It has been suggested this was made for European use. The boxes are, nevertheless, typically decorated in Burmese fashion in light red, green and yellow on a green or black hatch ground. The outside cover of each shows the twelve signs of the zodiac; the signs are slightly different to the European ones and are based on Hindu mythology. They are individually enclosed in the gwin-shet, or interlocking cells design, another popular motif. On the top surface of the covers the important emblems of the eight days of the week are depicted, each day being associated with a planet and a direction, following Indian tradition. The eight days are regarded as a symbol of Buddhist benevolence to all, and individual planets and days are prayed to for particular desired outcomes. This box entered the India Office Museum in 1867 so, in all probability, was made in the period 1850–1865. During the 19th century, the production of yun ware boxes was centred at Sa-le, south of Pagan, and it is likely this box was made there.

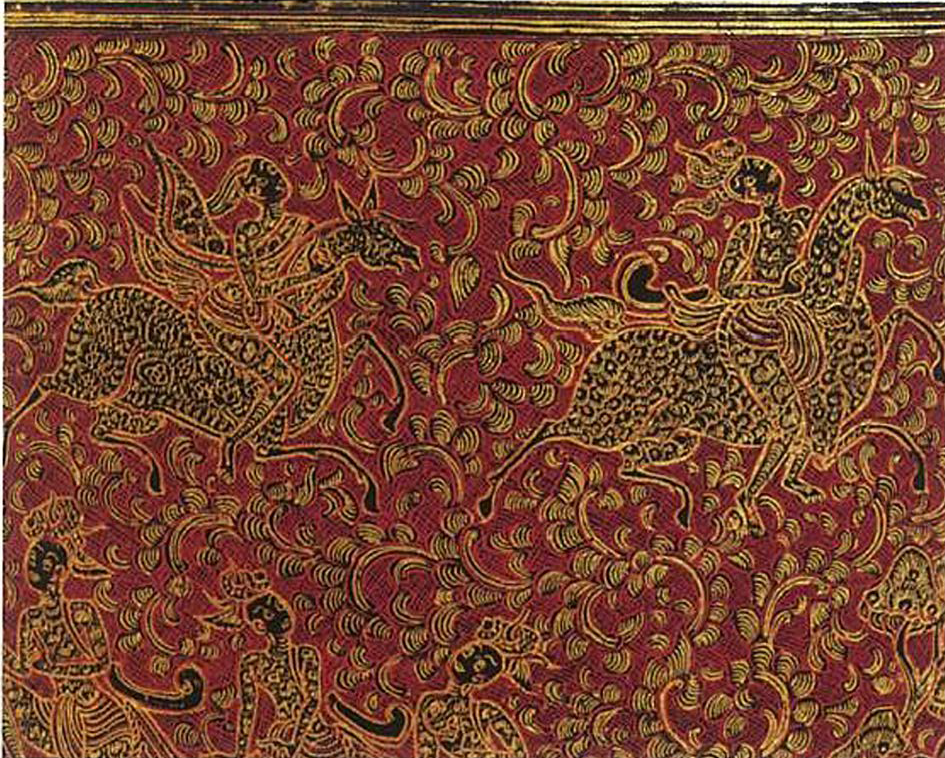

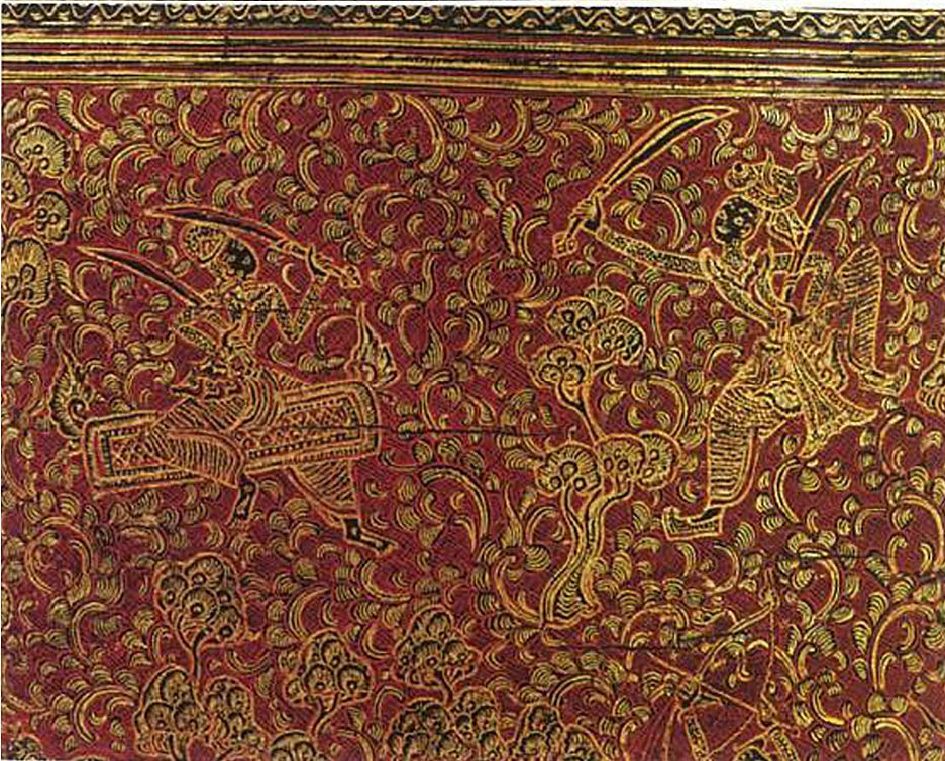

A different style of yun ware was produced in the southern Shan States, where Laikha was the main centre producing both engraved yun and moulded lacquer (see below). The finest example of Shan lacquer in the V&A collection, most probably from Laikha itself, is a large circular bi-it, a cylindrical box used by women to contain jewellery, cosmetics or small items of clothing (4). Two shallow lacquer trays at the top, and the larger space beneath, were used to accommodate such things. The outside cover of the drum is decorated in scenes from an unidentified story in black and gold on a red background, the engraving being of superb quality. The top shows elephants and goats standing amongst trees and foliage (5). On the sides of the drum the narrative features four horsemen (6), men with curved dhas, or swords, fighting close to a woman archer (7), and an ogre on horseback. The scenes are executed with great freedom of line and all the figures are in movement within floating vegetation, which gives the entire narrative a vibrant, energetic quality often missing from more meticulously drawn designs. The slightly flaring rim is a feature of Shan lacquer that does not persist beyond the middle of the 19th century, suggesting a date just prior. Richard Blurton identified a possible pair to this box in a slightly smaller, but equally magnificent, kun-it, or betel box, at Kedleston Hall. Both were collected by Lord Curzon while Viceroy of India, either in 1901 when he visited Burma or in 1902/1903 during the Indian Art Exhibition in Delhi, of which he was a patron.

A woven basket covered in yun lacquer, also from the Shan States, (8) was most likely used to carry the ingredients of the betel nut quid: the Piper Betel leaf, shavings of the areca nut and spices such as cinnamon, cloves and cardamom. Chewing betel was once an important social custom at all levels of society and part of court ceremony. Smaller boxes, such as this, would have been made for personal use, while larger versions were for communal use. The scenes on the lid and sides of this box (9) are drawn in black, yellow and green on a red lacquer background. These colours have faded on its top and sides, but from the areas on its footed base and inner tray where they have survived, it is evident that a bright green was originally a key element. The inner tray depicts an ogre, or bi-lu, on its underside (10). The unidentified scenes on the box’s side and top show warriors with curved swords, palaces with spires (pyatats), an archer and a man on an elephant. The box entered the East India Company Museum in 1855, and so is likely to date from shortly before that, perhaps to around 1850.

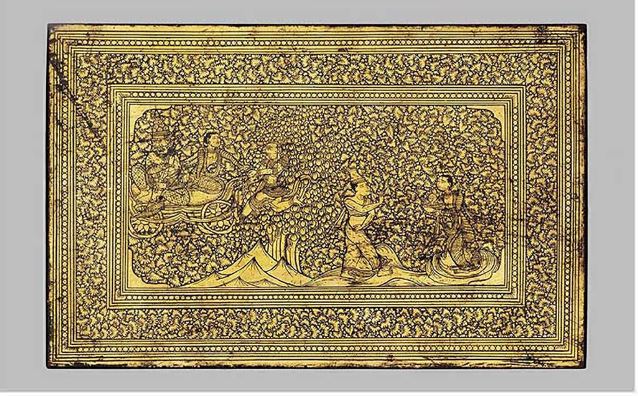

A strikingly different flat decorative effect is produced by applying gold to black lacquer (shwe zawa). The technique, used by a highly skilled craftsman, is seen on an interesting hybrid object (11) consisting of a mid-19th century English wooden cash box, which has been decorated in Burma with scenes from the Ramayana, an Indian epic popular throughout Southeast Asia. On the lid of the box, Sita, the beloved of Rama, is shown offering fruit to a mendicant who wears a tall hat, but who is actually the demon Ravanna in disguise. Immediately to the left, she is shown being abducted by Ravana and another demon in a cart. The figures are embedded in a dense pattern of toothed leaf forms called maw-pan. On the front side (12), Rama is shown again, raising his bow to shoot at a deer who, now hit by several arrows, reveals itself to be the demon Maricha in disguise. In the borders of the last scene and on each of the other sides, guinea pigs, emblems of those born on a Friday, are depicted. This suggests that a Burmese person commissioned the decoration of a British box. The box was accessioned by the India Office Museum in 1867, and so may date to about the period 1850–1865. As the British had a presence in Burma after the ceding of Tenassarim and Arakhan in 1826, and of Lower Burma after the end of the Second Anglo Burmese War of 1852/1853, the opportunities for local people to acquire such objects must have increased. The towns of Prome (Pyay) and Martaban were renowned centres of schwe zawa production in the 19th and the early 20th century, although by 1919 production had virtually died out in Prome. In the opinion of Sylvia Fraser-Lu, this box may be the work of Hsaya Pa, a master lacquer craftsman working in Prome at that time.

Prome was also especially noted for its scripture chests, with scenes from the life of the Buddha, created in the same technique. Gold on black lacquer is seen to perfection on Buddhist manuscript chests made in Thailand during the 16th and 17th centuries. The conquest of Ayutthaya by the Burmese king, Hsin pyu hsin, in 1767 led to an influx of artisans and a flowering of arts in Burma. It is likely that the schwe zawa technique was one consequence of this new influx of craft skills (see below).

In this technique, the artist paints in the design to be left as plain lacquer with neem oil, a vegetable oil from an evergreen tree (Azadirachta indica) found in the Indian subcontinent, and orpiment. A thin layer of lacquer is added to the area to be coated with gold. Gold leaf is then applied over the entire surface. After twenty-four hours of drying, the piece is washed and the neem and orpiment, and the extraneous gold, are all washed off, leaving the gold designs showing against the black surface. The water is filtered so that the gold leaf washed off in this process can be recovered.

Another high quality example of the same technique is seen on an offering bowl (13), one of a pair accompanying the shrine originally from the Palace at Mandalay (see below). This is beautifully decorated on its sides with the golden figures of kein-naya (the Indian kinnara), mythical beings whose upper half is human and whose lower half is bird, and a dancing zaw-gyi, or alchemist/magician, holding a stick behind his back in characteristic fashion. The figures are framed in cartouches, while around the top and bottom is a repeating petal design, kya hlan, and just above the figures the interlocking rope pattern (la cheik). The rim is made of gilded moulded thayo lacquer. Like the other accoutrements and the shrine itself, this probably dates from the period 1860–1880.

A very different type of gilded raised lacquer is represented by the small footed bowl (14) in black and gilded lacquer from Kentung, a Shan State bordering both Thailand and Laos. These vessels, called ko-kaw-tee in the Shan language, were originally used to contain rice flour at religious festivals or for special presentation purposes. Before the late 19th century, they were much plainer, but lacquer workers were encouraged by Mr Gahan, a colonial administrator, around the turn of the 20th century to begin to make them more decorative to increase sales to local people and make them more attractive to an early tourist market.

Relief figures of local tribal couples, together with crows, tiger’s faces, and more purely Buddhist emblems, begin to appear from this time onwards. This bowl displays such decorative motifs at each corner, which relate to legends surrounding the founding of the Shan State. The maker’s signature and date of manufacture in gold on black lacquer also became customary. This piece can be dated by its inscription to 1948.

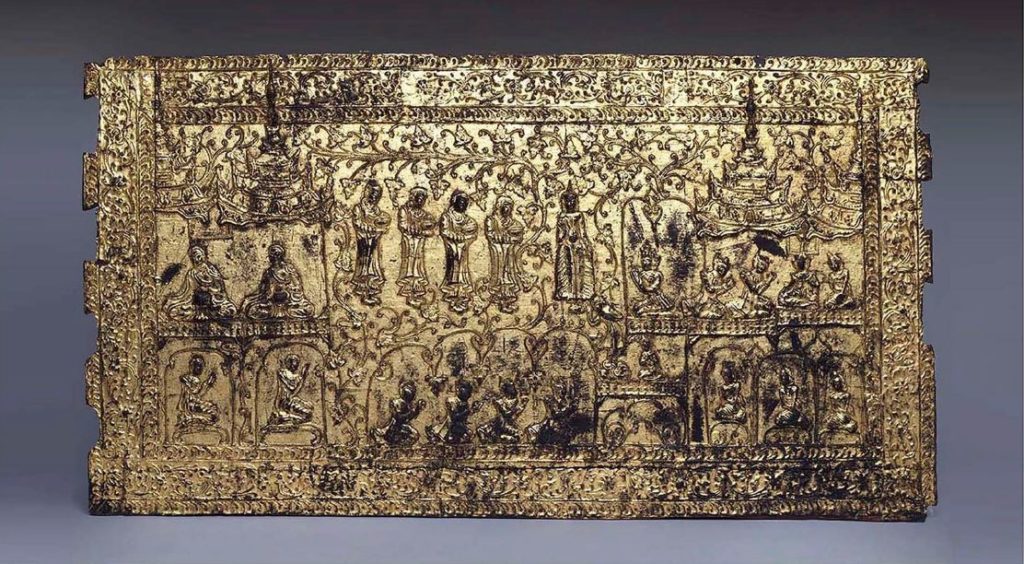

Some of the most spectacular lacquer objects ever produced in Burma were created using the technique of moulded lacquer, or thayo. By kneading together the crushed ashes of cow clung with heated thit-si resin, a pliable putty-like substance is created that can be formed into shapes, pressed into moulds or rolled between the fingers to make threads. Such threads and other shapes can then be stuck onto surfaces to be decorated, using lacquer as glue and, when dry, the whole raised design may be gilded. The technique is often seen on the outside of the chests, or sadaik, used to house religious books and manuscripts. In the V&A collection is the front panel from a sadaik dating from the late 18th century, which comes from a monastery at Taundwingyi, 160 kilometres south of Mandalay (15). The border of scrollwork encloses a scene from the life of the Buddha, where a line of four monks, or poongyi, are offering their food bowls to Buddha, who is surrounded by a meandering “vine scroll” that spreads across the entire surface, enclosing groups of worshippers. These include, to the left, four monks who kneel in reverence or are seated, perhaps in meditation. To the right of the main scene, a palace is depicted in which courtiers kneel in reverence before a prince, perhaps the Buddha before he had renounced his secular life. Sadaik are usually constructed, as is this piece, of solid slabs of teak with the corners dovetailed together. The entire surface of the thayo, which is black in colour, has been gilded, a technique called shwe cha. Chests were either open at the top or had cabinet style doors at the front, and most would have been raised on four legs.

Thayo was also used to decorate htsun-ok, vessels on stands with lids in the form of stupa spires (16), which were used to take offerings of food to a monastery on festival days. Splendidly decorated pieces, such as this one, would have been owned by wealthier families. The base would have contained larger or heavier items, such as rice or fruit, while trays above contained curry, pickles or betel ingredients. Macie of either wood, or as here of spirally woven bamboo with a spire of turned wood covered in lacquer, the scrolling decoration of thayo putty is typical of work done at Mandalay, although this item was acquired in Prome. The last capital at Mandalay, from its building and occupation in 1857–1860 to its fall in 1885, not only housed the king and court, but was highly important as a religious centre and the location of many monasteries. Together, this created a steady demand for lacquer vessels and objects of many varied types. The Sangha, or Buddhist clergy, required begging bowls, manuscript chests and covers for books of scripture; while the king would be the commissioner of the finest and most elaborate vessels needed for ceremonial occasions and to mark his status. The production of the finest quality pieces, presented by the king to the deserving nobility, was strictly controlled, including the materials and the types of decoration that could be placed on it for each level of courtier. With so many demands for high-end objects, it is not surprising that decorative techniques that created striking visual effects would become well developed in the capital during those decades.

Another such technique, called hman-zi shwe cha, combines raised lacquer putty with inset coloured mirror work to create glittering surfaces. This form of decoration continued after the fall of the court and is still practised in Mandalay today. Often found on manuscript covers, scripture chests and offering vessels, it is seen on a splendidly decorated headdress in the V&A’s collection, intended for use during theatrical or dance performances (17). The tiers of the crown are metal fitted onto a wooden base, the florets around the fillet and the “jewels” on each tier are shaped lozenges of red and green glass and mirror work set against the gilded lacquer. The quality of workmanship suggests this was made for performances at the Mandalay court, and its form is similar to that found in images of the royally crowned Buddha, with its spire shape and fillet at forehead level. This crown type, seen also in Buddha images, only appears in the…

Click here to access Arts of Asia‘s September–October 2017 issue for the full article.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift