MAXWELL K. HEARN

Douglas Dillon Chairman, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

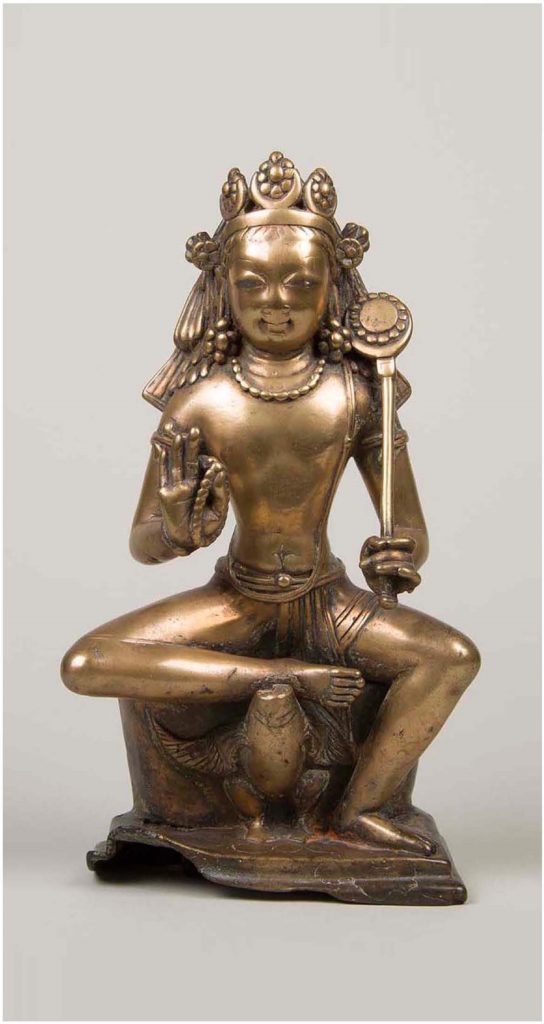

ON MARCH 16th, 2015, Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum announced the gift of 1275 Asian works of art from Florence and Herbert Irving—a donation that has fundamentally transformed the holdings of the museum’s Department of Asian Art. Like the Hindu deity Ganesha, the remover of obstacles (1), the Irving gift, together with their other benefactions, has cleared a path for the future on the occasion of the celebratory launch of the centennial of the Department of Asian Art. Herb and Florence Irving have personally witnessed much of the past century, and for nearly half of that time they have been building one of the most extensive collections of Asian art in the world (2).

The Irvings’ love affair with Asian art dates back to the early 1970s. Florence, who has said she must have been Chinese in a former lifetime, was earning a Master’s degree in education after having been elected to the Old Westbury school board. On her way to school, she often passed the office of the landscape architect Shogo Myaida (Maeda, 1897–1989). One day, she visited the office and struck up a friendship with Mr Myaida. Soon, she was planning a Japanese garden in their front yard. On a trip to Japan to scout for stone lanterns and other garden ornaments, Florence and Herb were advised by their decorator to look up the art dealer Alice Boney (1901–1988). As Herb relates, an initial dinner with Ms Boney turned into a full week of visiting temples, gardens and other sites together. Thus was born a remarkable friendship. For many years afterwards, Ms Boney would routinely send artworks to the Irving home, allowing them to have their pick. Very few works of quality ever exited their door.

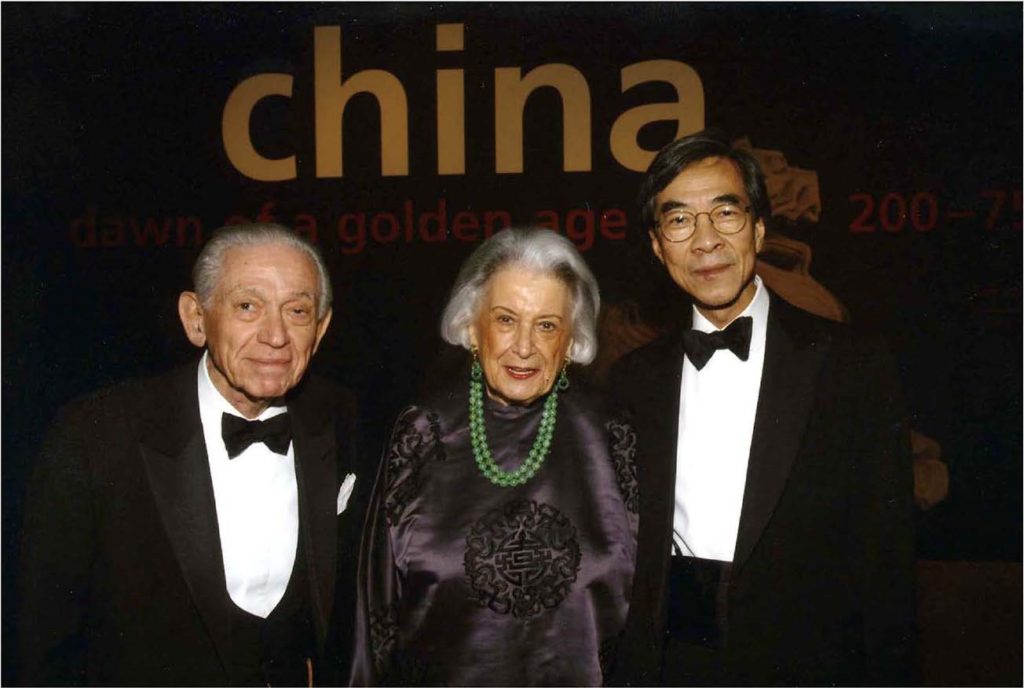

Another important friendship initiated by the Irvings was with James C.Y. Watt (3). Florence and Herb first introduced themselves to James Watt shortly after he became curator of the Department of Asiatic Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1981. On subsequent visits, they always made a point of calling on him. In 1985, James joined the Department of Asian Art at the Met and had a chance to visit the Irving home and become personally acquainted with their collection. As one of the world’s foremost experts in Chinese jade, lacquer, ceramics and other decorative arts, James Watt was the perfect curator to appreciate the Irving Collection. He immediately brought curators, Wen Fong and Martin Lerner, to visit the collection in Old Westbury. Perhaps his greatest feat, though, was persuading then Director, Philippe de Montebello, also to visit the Irvings. According to Herb’s account, Philippe had resisted visiting for months, claiming that there was no worthwhile art on Long Island. When James at last accompanied Philippe on a visit, the two of them stayed the whole day admiring works of art. As they prepared to depart, Philippe remarked, “Florence and Herb, we have to get married”. Philippe proposed that Herb become a trustee, but Herb demurred in favour of Florence, who had also served as a trustee of the Brooklyn Museum. Florence was duly elected a trustee in 1990 and became one of the most beloved members of the board. In 1996, she was elected a trustee emerita. She also served on the Department of Asian Art Visiting Committee and chaired the Department’s support group, the Friends of Asian Art.

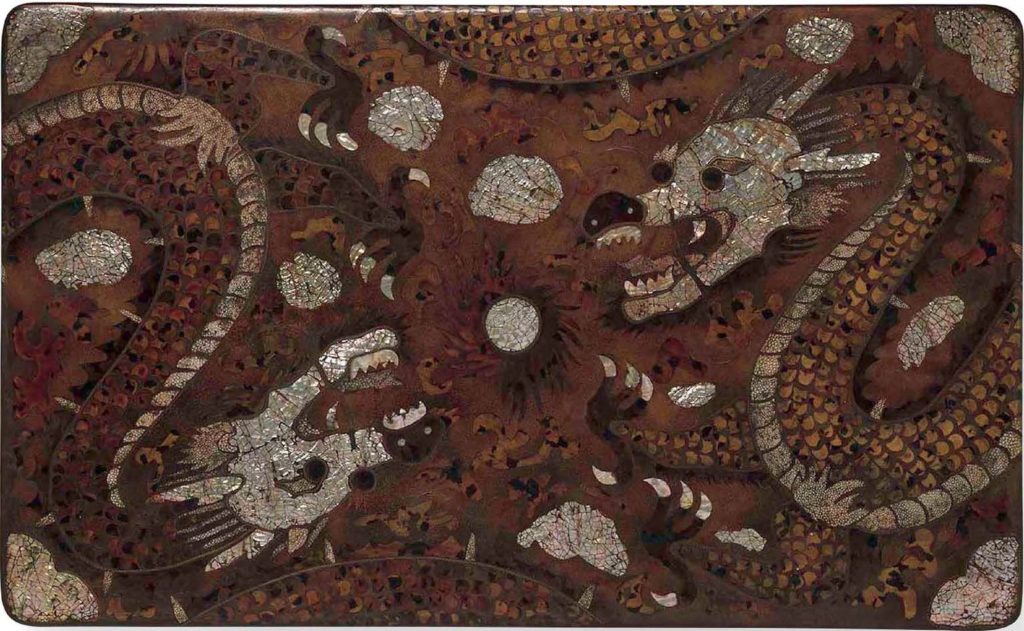

With James Watt’s encouragement, the Irvings began adding a number of fine examples of East Asian lacquerware to their collection (4) in the late 1980s. Their passion for lacquer culminated with the opening of the spectacular exhibition, “East Asian Lacquer: The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection”, in November 1991 (5). Co-curated by James Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, curator of Japanese art, the exhibition catalogue stands as a definitive scholarly resource for that medium. The magnitude of the Irvings’ achievement in this one area was summed up by Philippe de Montebello in his Foreword, where he characterised the collection as “one of the most distinguished and comprehensive assemblages of Asian lacquer to be found in the Western world”.

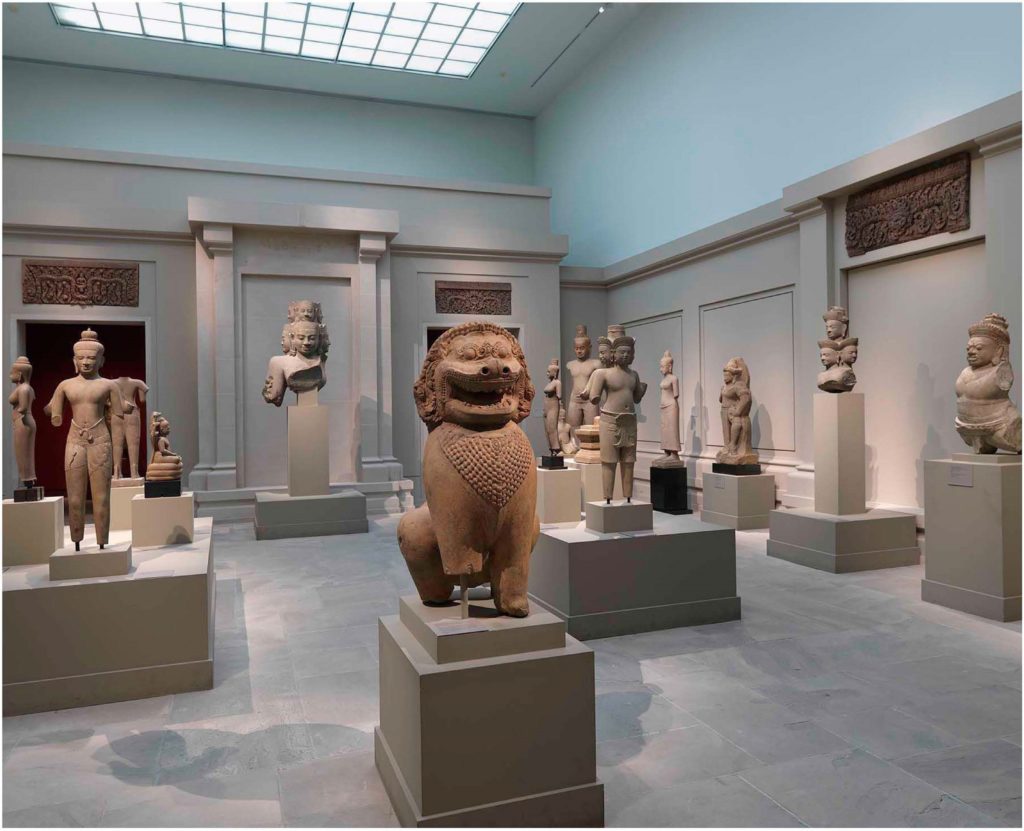

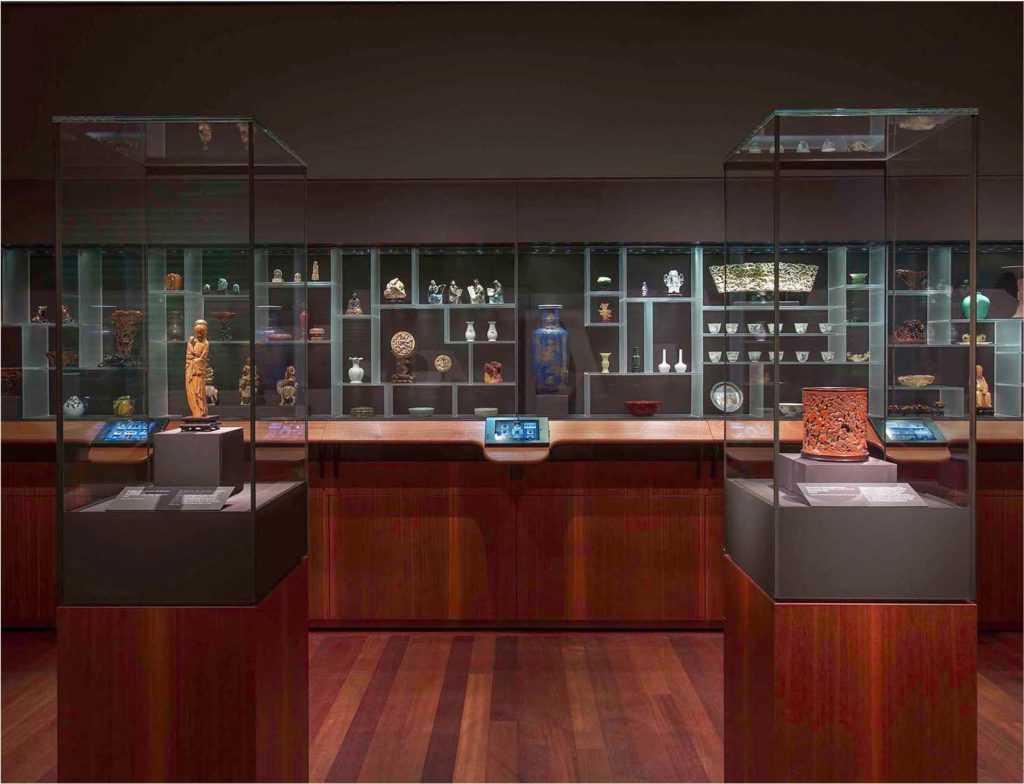

Three years later, in April 1994, the museum opened the Florence and Herbert Irving Galleries for South and Southeast Asian Art, giving the Metropolitan the most extensive display space for these arts anywhere outside Asia (6). Created under the curatorial guidance of Martin Lerner and Steven Kossak, this suite of eighteen galleries, covering 13,500 square feet, presents more than 800 works of art, including a number of Irving gifts. Then in 1997, reflecting their abiding interest in Chinese art, the Irvings supported the opening of the Florence and Herbert Irving Galleries for Chinese Decorative Arts—an entirely new third-floor display space, designed under the direction of senior curator James Watt that added 3000 square feet to the Asian Wing. These galleries feature discrete spaces for the display of Chinese textiles, jades, metalwork, lacquer and a newly renovated “Chinese treasury” (7). With these two benefactions, Florence and Herb Irving joined trustees, Douglas Dillon and Brooke Russell Astor, as among the most generous supporters of Asian art in the history of the Metropolitan. Their ongoing support was further recognised in 2004 with the naming of the second floor of the Fifth Avenue wing of Asian Art in their honour.

In the same year, in acknowledgment of their important support for the museum’s Thomas J. Watson Library—through the creation of a book purchase fund and an endowment to support the library’s ongoing maintenance—the library’s main reading area was named the Florence and Herbert Irving Reading Room. In a further mark of their support for the institution, they endowed in 2011 the position of Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia, which is currently held by John Guy (see John Guy’s article in this issue).

The Irvings’ most recent gift of almost 1300 works of art encompasses all of the major cultures of East and South Asia and virtually every medium explored by Asian craftsmen over five millennia (8). Areas of particular strength are Chinese, Japanese and Korean lacquers, South Asian sculpture, Chinese jades and hardstones, scholars’ objects of ivory, rhinoceros horn, bamboo, wood and metalwork, Japanese ceramics, and Chinese and Japanese painting. Taken together, this transformative gift fills gaps and extends the Met’s existing strengths in a way that will further elevate the museum’s stature as one of the world’s premier collections of Asian art.

Among the highlights of the Irvings’ gift is an outstanding selection of South and Southeast Asian sculpture. Notable are early Hindu images from 8th–9th century Kashmir (9), important mediaeval stone sculptures, including the iconic 12th century dancing celestial (10), several early Tibetan polychrome stone images (see John Guy’s article), and an extremely rare form of Shiva from 10th century Angkorian Cambodia.

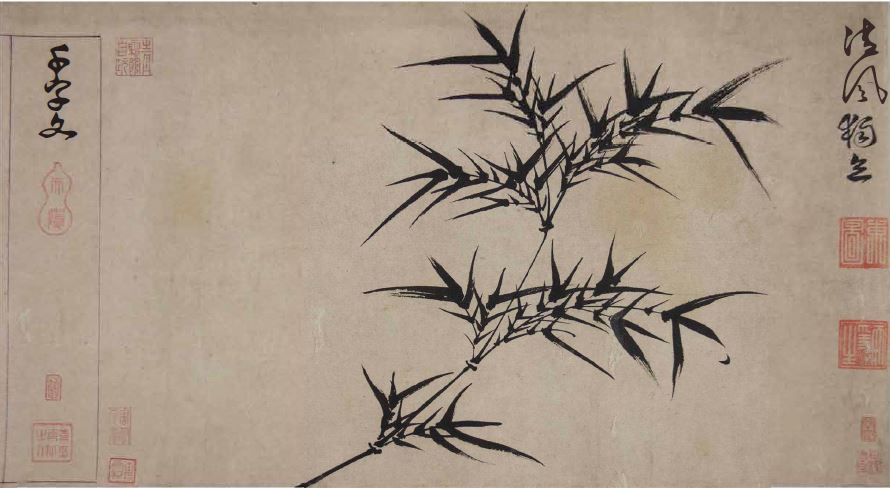

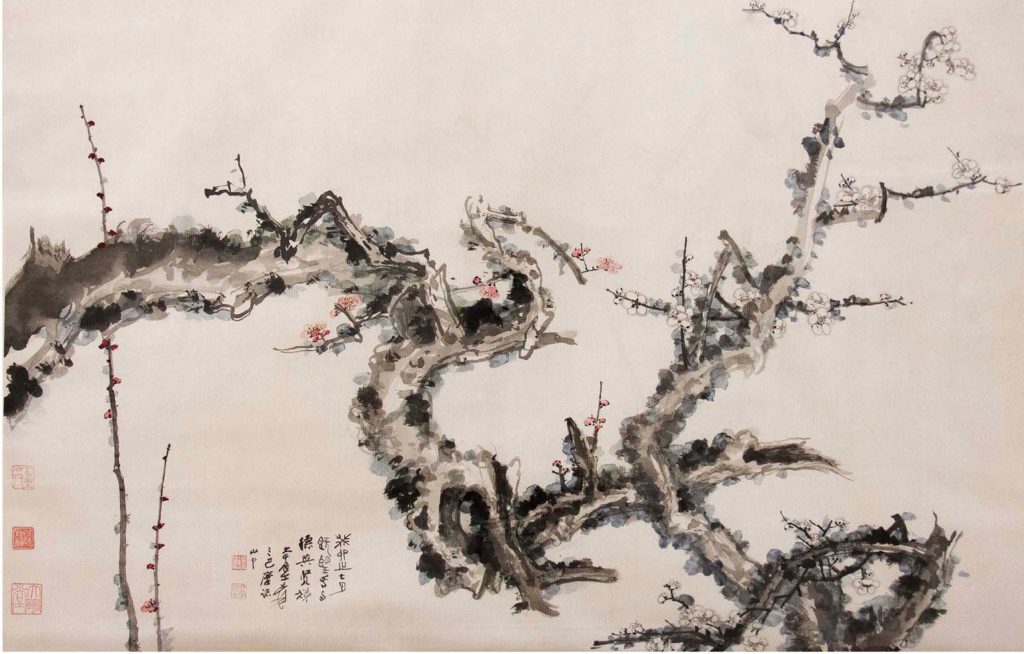

By far the largest portion of the Irving gift comprises a diverse array of Chinese works of art, including calligraphy (11), paintings (12), ivories and bamboo carvings (see Pengliang Lu’s article), and some 500 jades and hardstones (see Zhixin Jason Sun’s article). Such works, long associated with the intimate arts of the scholar’s studio, importantly broaden and deepen the museum’s coverage of China’s mainstream literati cultural tradition.

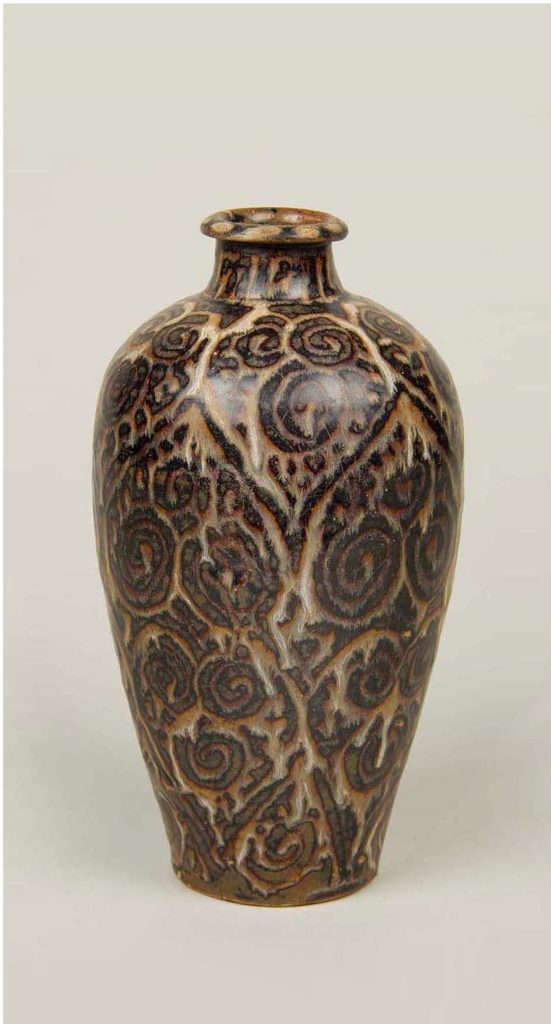

Among the many treasures encompassed in this rich body of material are the Irvings’ superlative holdings of East Asian lacquer (13). An area of comparative weakness in the museum’s holdings prior to this gift, this fundamental medium of East Asian artistic expression is immeasurably strengthened by the Irving donation of 224 Chinese, Japanese and Korean lacquers ranging in date from the 1st to the 20th century.

The 141 Chinese lacquers in the Irving Collection offer a truly comprehensive picture of the medium across two millennia, from the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) until the end of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) (see Denise Patry Leidy’s article). The small but choice selection of eleven Irving Korean lacquers represents the finest such assemblage in the West, with two Joseon period mother-of-pearl inlaid boxes (one from the 15th–16th century and the other from the 18th century), a 19th century box with dragon decoration inlaid with tortoiseshell and ray skin in addition to mother-of-pearl, and an 18th century red lacquer box with painted ox horn embellishments (see Soyoung Lee’s article). The seventy-two lacquers from Japan (see Monika Bincsik’s article) include more than a dozen fine examples of Negoro ware, noted for its evocative patina of an under layer of black lacquer showing through the red lacquer surface coating, as well as more than forty superlative examples of late mediaeval and Edo period pieces embellished with pictorial motifs rendered using gold and silver powder. There are also a few rare examples of so-called Nanban (“Southern Barbarian”) lacquer, referring to the earliest group of lacquerwares produced for export to the West, and a select array of lacquer works produced in Okinawa (one of the Ryūkyū Islands).

A final area of strength in the Irving Collection is a significant group of Japanese Zen paintings and calligraphies (see John Carpenter’s article) as well as an array of richly coloured paintings of the Edo period (1615–1868) (14).

The story of the Met has always been punctuated with extraordinary gifts from collectors and supporters committed to sharing with the public the art they love. As we mark the centennial of our Asian Art Department and celebrate its distinguished collection and the many donors who have contributed to its pre-eminence today, we particularly honour the transformational gift of works of Asian art from the Irving Collection that has so dramatically enhanced the quality, breadth, and depth of the museum’s Asian holdings (15).

This issue of Arts of Asia presents a selection from the 1275 works in the Irving’s 2015 gift. Each article is authored by one of the curators in the Department of Asian Art and highlights a small number of representative pieces. A full assessment of the importance of the Irving Collection will take scholars several generations to reveal. Already, however, the Irving gift has immeasurably enriched the museum’s display of Asian art, enabling the Metropolitan to present the world’s most comprehensive narrative of Asia’s cultural achievements at the highest level of quality.

Click here to access Arts of Asia‘s November–December 2015 issue for more.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift