MARTIN KURER

Photographs by AT MACULANGAN

Introduction

This article has been written from the viewpoint of a collector of Asian and American contemporary art, who wants to understand Philippine Cordillera tribal art sculpture in the context of aesthetic expression in today’s art world. I have increasingly been drawn to the powerful simplicity of the tribal—or traditional—art form, with a focus on Cordillera tribal art, created by the tribal peoples, mainly Ifugao, Bontoc and Kankanai, inhabiting the great rice terraces in the mountains of Northern Luzon, Philippines. I find the aesthetics, rather than the ethnological background, fascinating.

This approach is quite similar to that of William Rubin in his introduction to “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art, which accompanied the exhibition of the same title at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1984. I want to understand these primitive sculptures in terms of the “Western” context in which modern “artists” discovered them. To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever suggested, and this article does not suggest, that “Western” modern “artists” discovered Cordillera tribal art, rather the “discovery” was made by “cross-collecting contemporary art enthusiasts”.

So my focus will not be on the ethnographical and ceremonial context, nor on the question of the true meaning of “authenticity”, nor on the level of encrustation produced during animistic ritual, all of which has been widely discussed. Rather, the focus of this article is on aesthetic expression, although within the framework of ritual function. However, I acknowledge the spiritual position of the carvers and the environment in which the pieces were created. Thus, my view is not contrary, but rather complementary, to the traditional view. In this way, I hope I can introduce some new elements to the discussion of Cordillera tribal art.

Context

The influence of African and Oceanic tribal art on 20th century Western art is widely accepted, as demonstrated in the above mentioned exhibition at the MOMA, and thereafter in the most striking catalogues and commentaries accompanying recent exhibitions and sales of African and Oceanic works published by Christie’s and in other publications.

In 1984, William Rubin brought attention to the lack of discussion of the impact of the discovery of tribal art on 20th century art: “No pivotal topic in twentieth-century art has received less serious attention than primitivism—the interest of modern artists in tribal art and culture, as revealed in their thought and work.” Today, that has completely changed in respect of tribal art in general, but unfortunately not significantly in respect of the art of those tribes discussed here. At last, however, there has been limited recognition in that some Filipino contemporary artists, most notably Gaston Damag—Ifugao by descent—Ronald Ventura, Eduardo Olbes and others, are using Cordillera artistic elements in their works.

It is not my intention to suggest that there was any contribution to “primitivism” when there was none. But looking at the aesthetic quality and at what we can derive from that quality today, the resemblances to tribal art leading to “primitivism” are striking. There are good reasons for this, as will be shown below.

George Braque once observed: “African masks opened a new horizon to me. They made it possible for me to make contact with instinctive things, with uninhibited feeling that went against the fake tradition (late Western illusionism) which I hated.” Primitivism “showed up at the end of the 19th Century ‘postindustrial’ period when Europe was enduring a period of cultural decadence and ideological crisis.” The artists “were seeking a new simplicity and directness of expression”, and contemporary artists still do.

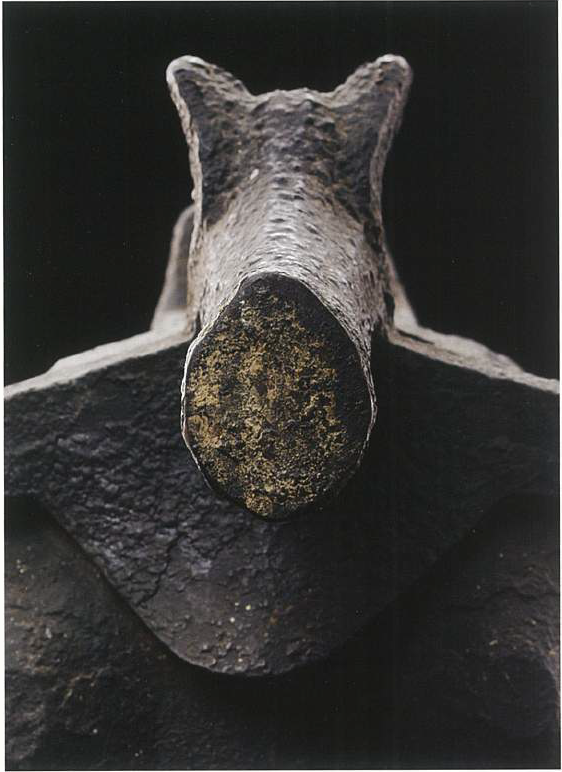

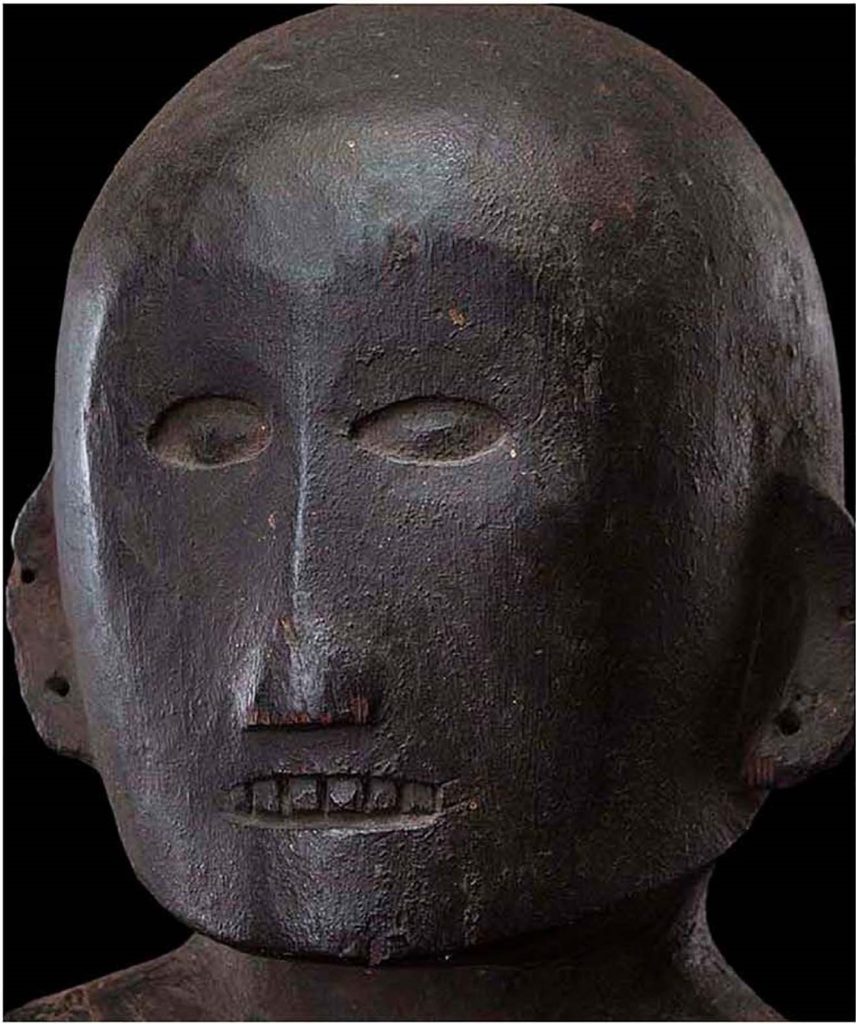

Cordillera tribal art, therefore, deserves a closer look. I believe that the artistic quality of Cordillera tribal art is equal to that which influenced 20th century, and now 21st century, art. This becomes even more credible when looking at the detail of the objects, and not just more traditional full-body views. Photography is essential in helping us see these details and the drama of the art form. Juxtaposing images of entire objects with close-ups that reveal unique angles, the connections and the sculptural details (whether figurative or abstract), helps the viewer truly grasp both the object’s expression and meaning. The result of photographer At Maculangan’s work reminded me of Kandinsky’s description: “In a mysterious, puzzling and mystical way the true work of art arises from out of the artist.”

Simple and powerful: expression in Cordillera traditional art

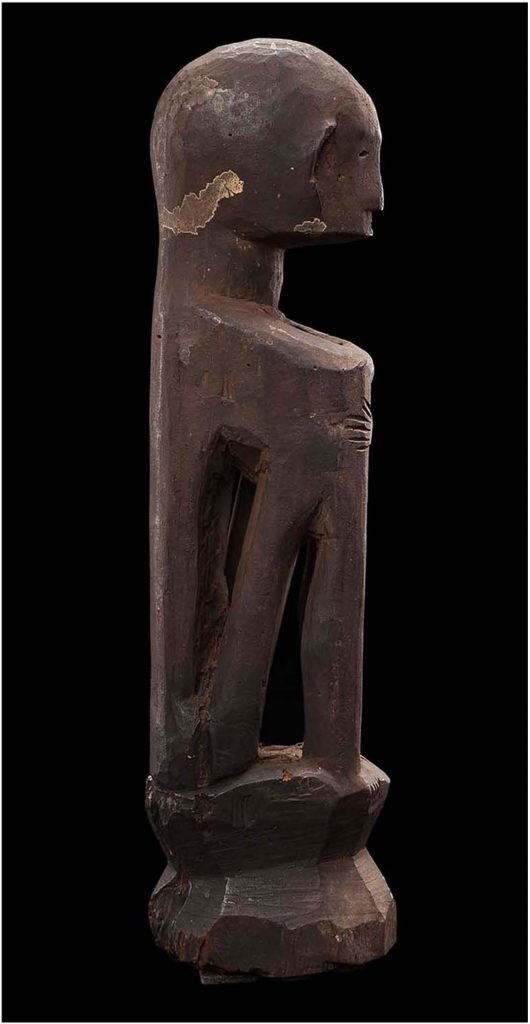

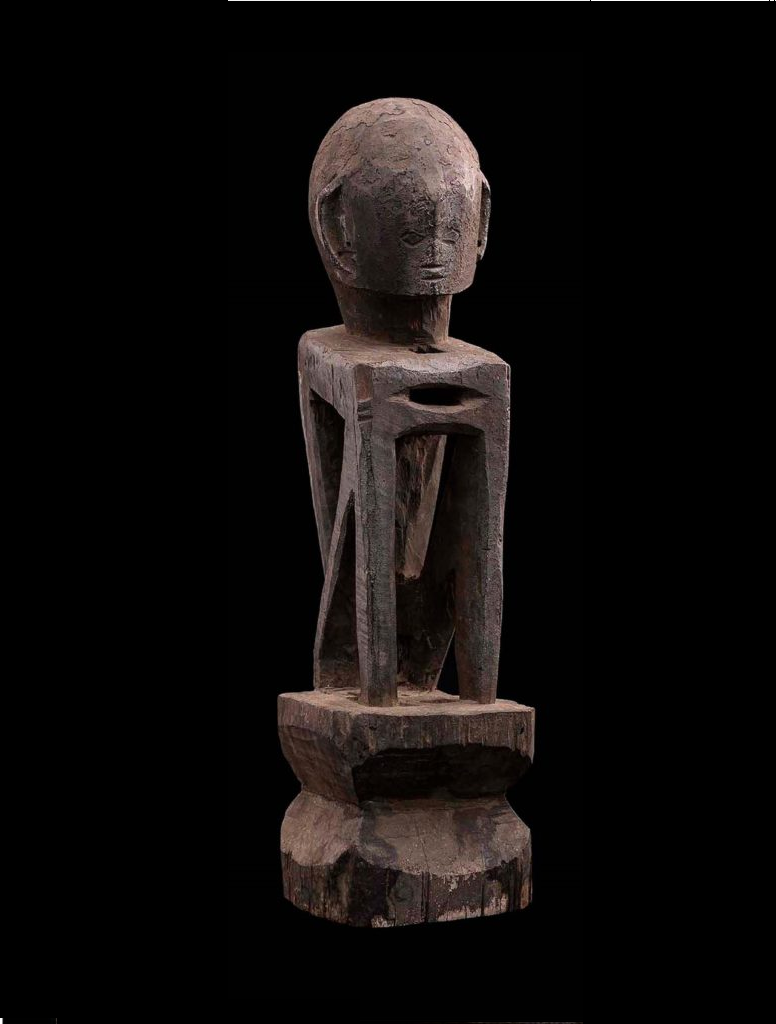

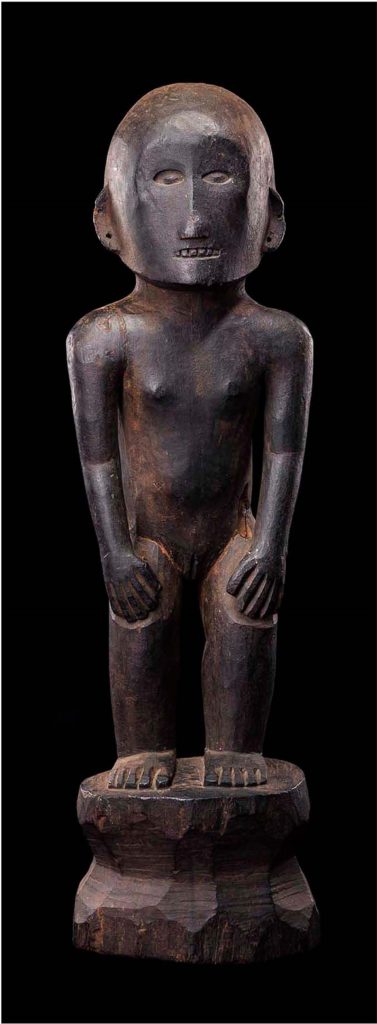

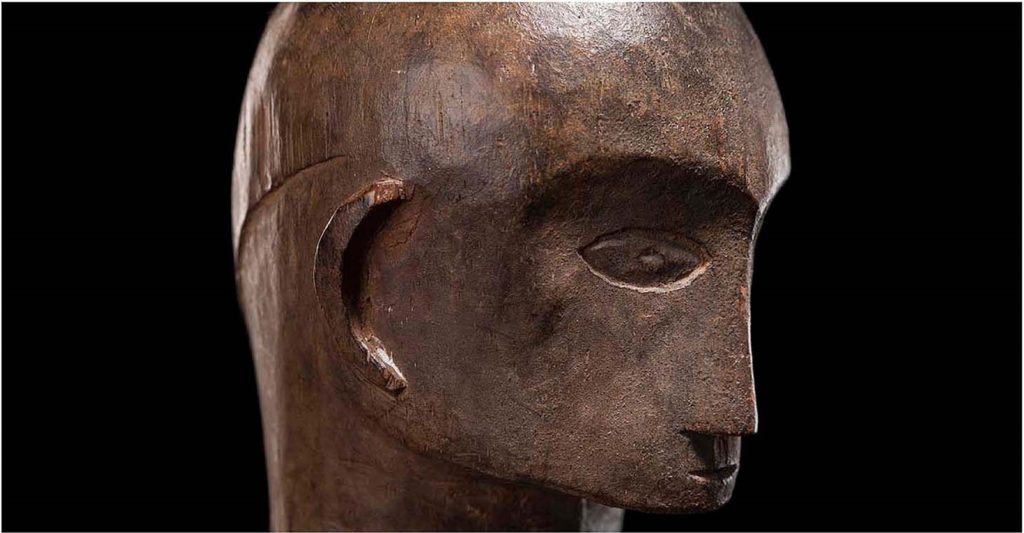

A male bulul (1), late 19th century, shows a conventional position, arms crossed, possibly Lagawe/Bunney style. The architecture and geometry of the sculpture is vertical, the back straight, as if the result of a forceful strike by an axe. The expression is reminiscent of the strict lines of Cubist sculptures, for example Femme au Compotier by Henri Laurens, 1920, or the sculptures of Alexander Archipenko (The Hero!), Raymond Duchamp-Villon or Jacques Lipchitz (Sculpture 1915), or Constantin Brancusi. The legs of this bulul rest directly on the base in the shape of a rice mortar, indicating a direct connection with the earth. The details of the head in (2) express the simplicity of the carving. There is only a semblance of the eyes, the ears, the nose and the mouth. Note, in particular, the hands resting on the thighs.

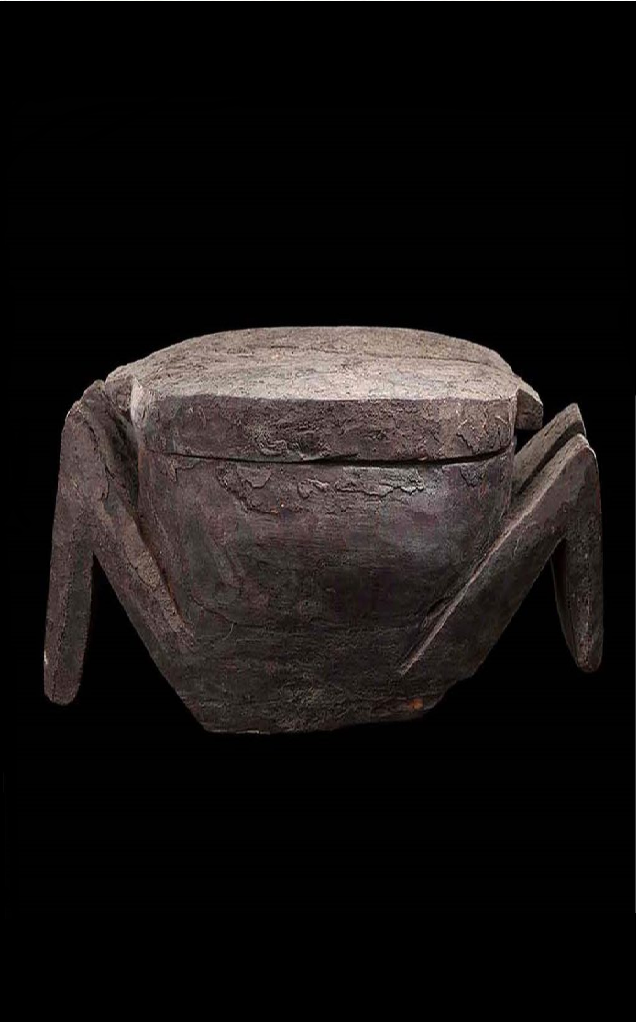

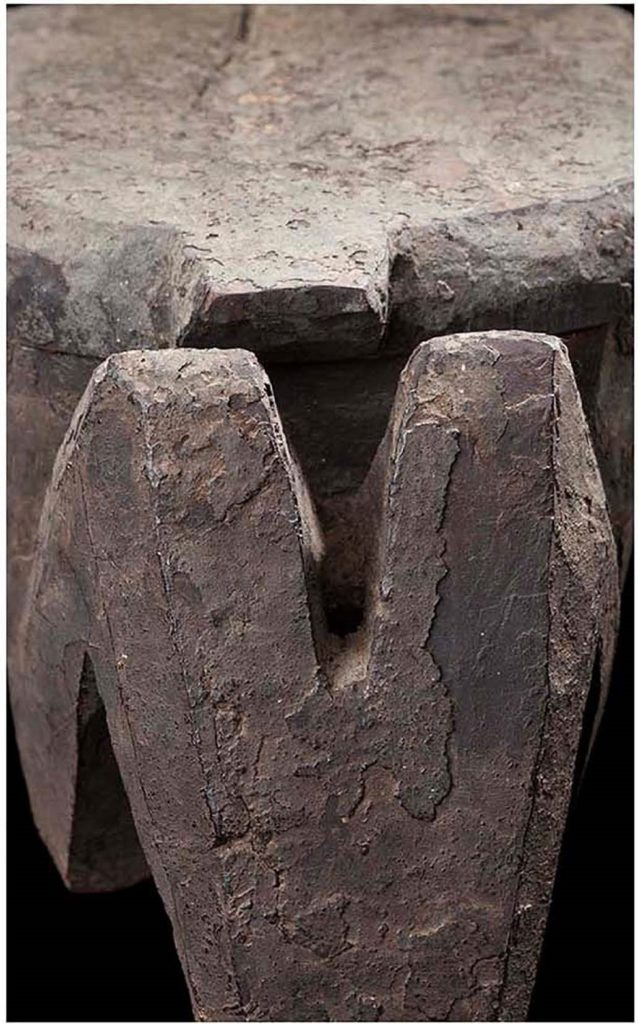

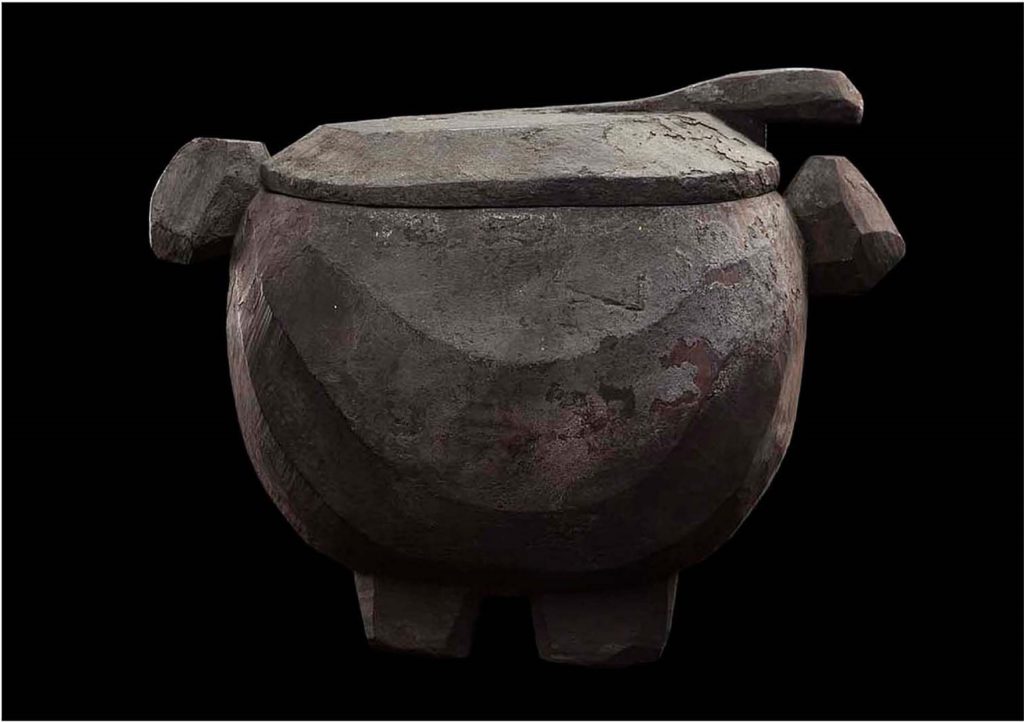

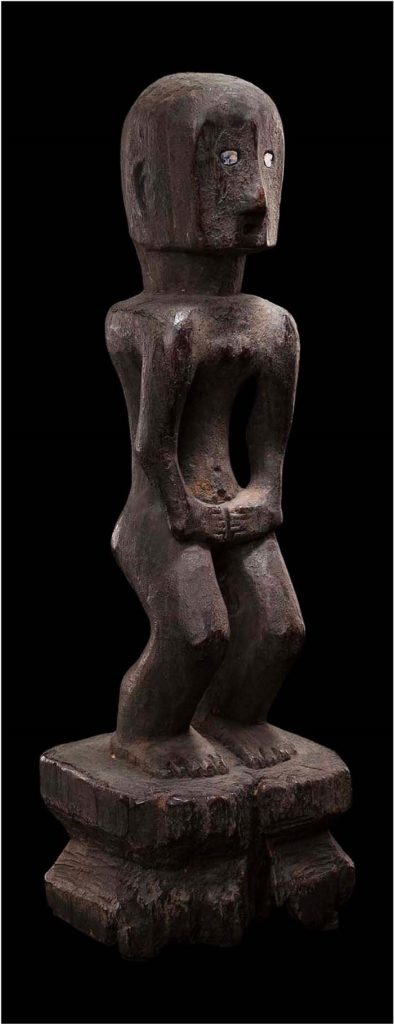

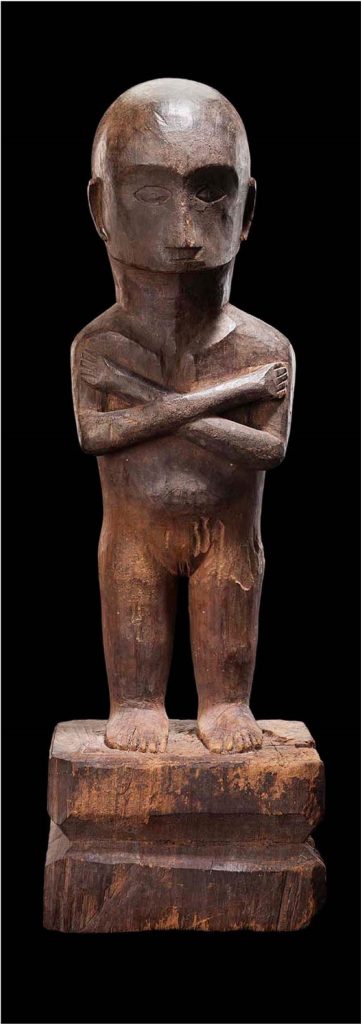

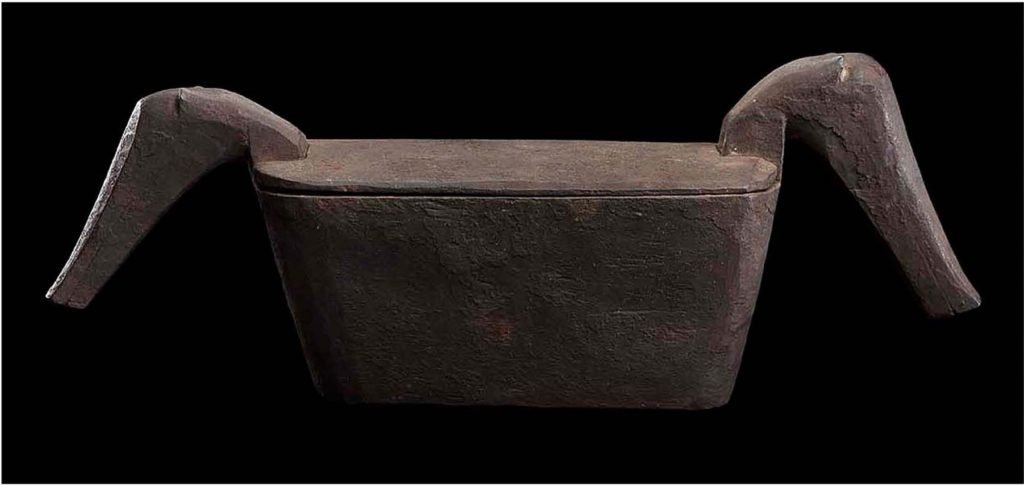

Another male bulul (3), late 19th century, shows a similarly simple expression, with a head completely out of proportion, but with clean geometrical lines (4). The body parts are even more reduced here. However, the directness and straightforwardness of the expression is exceeded by the carving of one of the most striking examples of ceremonial boxes I have ever come across, expressing the duality common to tribal life (5). Cordillera boxes usually have their handles fashioned as heads of animals, such as pigs, dogs, bird-like figures and occasionally water buffaloes. One cannot be sure what these animals represent. Usually the heads are almost identical on each side, although sometimes one is larger than the other (as in the case of a pair of bululs, representing male and female).

In an illustrative example (6), the carving reduces the representation of such heads to a functional feature, which would not be recognised looking only at the heads. In the context of the complete box, it becomes clear what the carving represents. Such representation is reduced to perfection, and we should also note the symmetry of this work of art.

A similar path was taken by the carver of a food box (7) whose greyish patina indicates deposits of salt crystals that have penetrated the wood over time. The heads are carved in a straightforward way, basically showing only the panes.

Those archaic pieces of Cordillera art express a “reduction and suggestion” (Floy Quintos), using a “technique of deletion, not decoration”. We come across such extreme reduction of the expression of sculpture also in works from Africa, where art is intended to try to show the essence using simple means without any unnecessary decoration. Representative examples include certain masks of the ngil type of the people of Fang of Gabon, such as the ngil mask of the Oyem region in the collection of the Museé Quai Branly in Paris, the geometrical sculptures of the peoples of Mumuye in north-east Nigeria, or the Mumuye statue in the collection of Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel.

Parallels can be found in the wood carvings of the autonomous peoples of Central Vietnam, and in some pieces from Sumba and Toraja. As in many works of those tribes, and the 20th century pieces they influenced, we can see the “breakdown of form into line, volumetric pattern and geometric rythm”, the “conceptualised” and “abstracted” language of expression, a “form of expression that spoke of the inner vision of the world, of a central reality removed from the illusion, what the West had termed ‘naturalistic’ appearance”. The expression is “striving for balance and symmetry”.

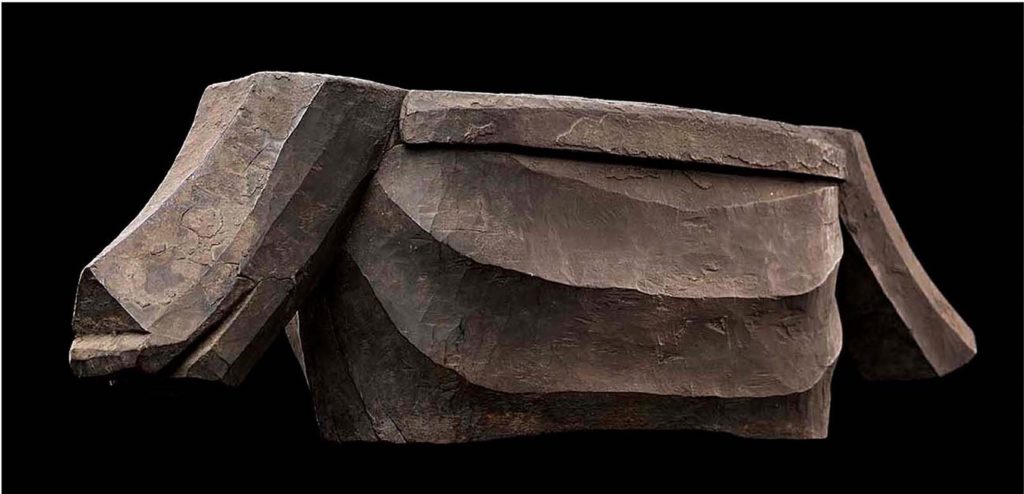

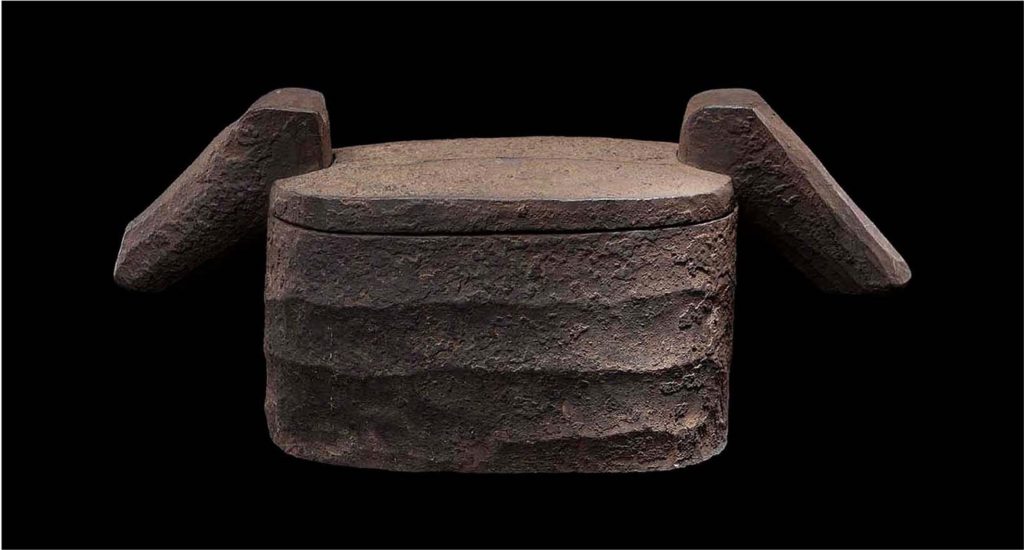

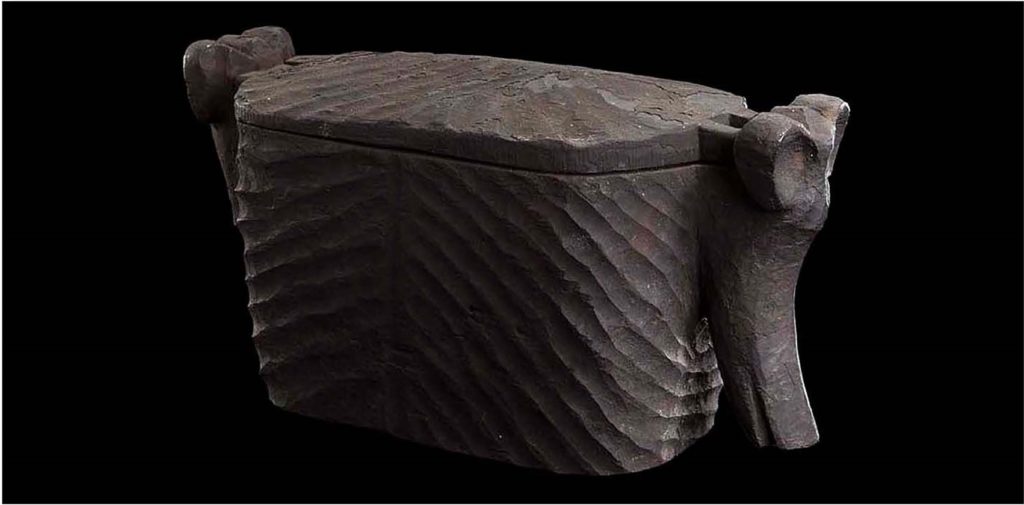

A ceremonial box (8) is a good example of the pure power represented in the carvings. Made in the early 20th century, this finely grooved ritual box has two stylised symmetrical pig heads that exude the hulking power of the wild boar common in the Cordilleras. We saw very similar, yet less detailed, features in (5) and (7), heads basically carved with a series of faceted planes (9). Those planes are echoed in the grooves of the side of the boxes, thus creating a minimalist and abstract expression, which we find in early 20th century art in Europe, such as in the work of Constantin Brancusi.

In this context it should be mentioned that Brancusi himself rejected the idea that his work was abstract, saying that what the “idiots” (the art critics, probably) called “abstract is really most realistic. What is real is not appearance, but the essence of things”. Showing this “essence of things” most probably is also what the Ifugao carvers had in mind.

The grooves are a frequent feature of boxes. Do they express the repetitive design of the rice terraces? Possibly they were, to a certain extent, following the grain of the hardwood used (Narra, Malave, Ipil, etc.). In any case, the contours imply an element of powerful calmness, as shown in (10). We see a combination of such powerful, wavelike grooves as we can see in (11), again with two stylised pig heads (eyes inlaid with porcelain shards), and a crouching figure on top of the lid. Note the short legs, again representing strength, and a firm stand on the earth, and connection therewith. This very important 18th (or earlier) century piece shows a deep patina, resembling iron (12).

This leads us to the more “frightening” expression of many archaic pieces, reflecting their function to keep away bad spirits. A fine example is a pair of mid-19th century bululs, very well preserved with porcelain shards indicating the eyes and the mouths, again with the arms crossed over the legs (13). The carving required enormous discipline.

Another frightening sculpture is a female bulul (14, 15), again an important 19th century piece from Hapao village. The hands are laid on the thighs, the hunkered body is slightly leaning forward, teeth bared, eyes staring straight ahead, giving it a very strong presence. We see a “clarity of form” rather than “the complexity of detail”.

The same can be said of the representation of another short legged boar, with eyes made of porcelain inlay, in a Bontoc food box (16), and another in an Ifugao ceremonial box (17) that has a cowrie shell for the right eye. The carving expresses physical strength, while the thick encrusted patina creates an unexpected aesthetic beauty. Given the fact that there was no ceremonial use, a thick crusted patina is absent from the boar meat container. However, note the fine lines displayed on the body.

In all of these pieces we can see a “sculptural vigor and audacity” that animates simple and often crude objects, elevating the focus beyond mere surface detail (Floy Quintos). We see an art concerned with expressing power, with volume rather than surface. The representation with its own vocabulary relies on suggestion, distillation, reduction, rather than style (Gaston Damag). See also (18), a powerful, stocky figure in the Hapao style.

A very fine example of more harmonious pieces is the female, (pregnant?) bulul shown in (19, 20). The hands crossed, no doubt a protective position, the eyes in the finely carved head directed slightly downwards, the sculpture exudes spirituality, an “otherwordlyness and humanity” (Ramon Villegas).

We can also see sculptures, which according to our contemporary knowledge, appear almost humorous, such as a food box with “Mickey Mouse” ears, heads with a sort of smiling snout, and a simple chunk of wood in between, with a sloping lid that allows easy handling (21). The AA:F collection also contains graceful and tranquil pieces, like the well preserved (including their clothes) late 19th century pair of sitting bululs (22), the ceremonial box with swan-like heads (23), or the box with very finely carved grooves (24).

In the late 19th and early 20th century, there was a movement towards more commercial, pleasant-looking, more “realistic” (Brancusi’s “idiots” would probably agree) and detailed forms of expression, in a period called “transition” (Floy Quintos). In essence, this change of style can be attributed to the…

Click here to access Arts of Asia‘s January–February 2017 issue for the full article.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift