GINO GONZALES

IN SO MANY WAYS, the dress of a nation reflects the psyche of its people. According to Oscar Wilde: “A history of dress would be a history of minds; for dress expresses a moral idea; it symbolises the intellect and disposition of a nation.” Beyond expressing the changing silhouettes and ideals of beauty, it also presents the internal struggles between polar forces that constantly shape a nation’s history. The Philippines and the nuanced evolution of its supposed National Dress is a vivid illustration of this ongoing saga.

The Indigenous and the Foreign (1500s–1600s)

Quite often, the definition of “indigenous” is tied in with the idea of a “pure” and “unadulterated” culture, often associated with Austronesian ancestry.1 Yet, assuming that “indigenous” Filipino is synonymous with the culture before the arrival of Spaniards in the archipelago in 1521, a more complex picture begins to emerge. Contrary to the idea of a monolithic indigenous culture, precolonial Philippines was teeming with foreign influences resulting from centuries of trade with neighbouring Asian countries. These “borrowed” cultures were eventually embedded into the lifestyle of the indigenous inhabitants of the islands, which are often subdivided into various ethnolinguistic communities.

These indigenous groups had distinct modes of dress, which differentiated them from one another; they were chronicled by Antonio Pigafetta, the Italian explorer, in 1521 and later depicted in the Boxer Codex paintings of the circa 1590s. The point of initial contact between indigenous Filipinos and the European explorers happened in the Visayas, where women’s dress primarily consisted of an upper garment resembling a short blouse and a lower garment similar to a skirt.2 The former was called baro, especially among the Tagalogs, who lived on the island of Luzon. Francisco Ignacio Alcina, the Jesuit missionary, noted in his Historia de las Islas e Indios de Bisayas (1668): “Their blouses or badu [baro] were so short, that they only covered the breasts and hardly reached the waist …”3 The latter generally came in two forms: the tapis (in Tagalog) — a rectangular piece of textile that functioned like a wrap-around skirt or the Asian sarong and the patadlog (in Visayan) — a multifunctional, tubular garment that can be girded around the waist as well as upper sections of the body. Textiles ranged from exquisitely woven abaca from local looms to trade goods from neighbouring China, Japan, Borneo, Indonesia and Malaysia.

Aside from the decorative accent on garments, the precolonial wardrobe was replete with gold jewellery. Accessories to the hair, teeth, ears, neck, arms, fingers and ankles, as well as fastenings of garments and weights on the ends of sashes, gleamed in abundance due to the precious metal and trade beads. The wide lexicon of precolonial jewellery bore striking similarities with traditions from elsewhere in Southeast Asia, but also boasted craftmanship that appeared unique to the archipelago.

Contact with the Spanish colonisers and Catholic missionaries in the late 1500s sparked a clothing evolution that mirrored the way other elements of indigenous culture reacted to the onslaught of the foreign. The popular narrative is centred around the scandalised missionaries and their attempts to give the indio women some decency by imposing a completely new mode of dress, which adhered to Western and Roman Catholic ideals of propriety. However, a few contemporaneous accounts hint at a more gradual process of adaptation and the reinterpretation of these “foreign” ideas into everyday wear. Alcina, for instance, suggested the resilience of ancient clothing habits, such as the use of tubular garments, decades after the Spanish conquest. He also mentioned the “vanity” of the indigenous women, who still meticulously styled their hair and applied body decoration in the “indigenous” manner.

Conversely, Alcina also narrated how Bisayan women of means started wearing enaguas blancas (petticoats) and sayas (skirts) that reached the feet. Renderings accompanying his text portrayed women wearing long-sleeved baros paired with skirts. Otherwise, “The women go about the house in their mantillas [most likely referring to the tubular garments] which are knotted at the waist, without any blouse or skirt. As a result of the intense heat, they cannot bear to wear any other clothing …”4

The Oriental and the Occidental (1700s–1800s)

By 1734, a street scene in Manila had been depicted by Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay, the Filipino artist, amongst other vignettes that form the margins of a map by the Jesuit priest, Pedro Murillo Velarde. It features a woman headed for church covered in a cobija, or mantle, with scapular on her neck (1); a fruit vendor wearing a loose camisa (a term used alternatively with baro) and a tapis wrapped around the waist (2); and a woman dancing in the distance in a similar outfit to the fruit vendor (3). Contrary to popular belief, many of these clothing components were not introduced by the Spaniards. In fact, most were primarily indigenous. The cobija had a counterpart in the native lambong, which functioned as a protective covering over the head and body. Yet, as a virtual veil for religious functions, it takes on new meaning — one particularly laden with piety.

Another vignette portrays a mestiza — or a female of mixed ancestry. She is wearing a camisa with embellishment around the neckline, shoulder seam and wrist. A fichu, called pañuelo, is added over the camisa. A precolonial tapis is worn over her voluminous saya — a rendition of the Western skirt. This image conveys an effort to conceal the body with layers in compliance with the Occidental idea of modesty. She also wears filigree jewellery on her ears and neck. Her hair is arranged in a bun resembling a spiral-like effect or rosette — an indigenous manner of arranging long hair.

This ensemble of the mestiza negotiates the disparity between Eastern and Western aesthetics, and is called traje de mestiza — literally the outfit of the mixed-race female. The pañuelo and the camisa are both made of sheer textile suited to the hot tropical climate. These lightweight and gauzy materials generally fall under the term nipis,5 which may include abaca, pineapple or cotton fibre. However, the diaphanous pineapple cloth, or piña, was the most coveted textile, which only the privileged class could afford.

In contrast, the lower garments are made of opaque material. Both tapis and saya are typically constructed from cotton or silk. While the upper garments are made of locally woven material, several lower garments were derived from imported material from the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade. Silks and brocades from China are fashioned as skirts. Mestizas, who wished to brandish their luxuriant skirts without the tapis, wore them as saya suelta — a look which differentiated them from the working class, who used the tapis primarily as practical protection for their simpler skirts.

The general outlines of Western dress were approximated by the traje de mestiza in the succeeding centuries. After the French Revolution, the empire line with its high waist was adapted belatedly by mestizas in the 1820s. Typos del pais paintings from the atelier of Damian Domingo document these sartorial choices, which were also adapted by the working class (1, 2). However, unlike the Western empire dress, the traje was still made of separate components, much like precolonial attire from centuries past. Aside from being an assertion of familiar clothing habits, the use of separates gave the wearer more flexibility in terms of movement and sartorial choice. While the mestizo class did not completely identify with their Spanish or Chinese ancestry, the same may be said of their indigenous roots. The fission between divergent roots resulted in a lifestyle and an outfit that fused both worlds (3).

Jewellery, inspired by indigenous, Eastern and Western traditions, included the peineta (decorative hair comb), fantoche (hair pin or veil pin), criolla earrings and tamborin necklace. Accessories from Asia included oil-paper umbrellas and abanicos (fans) made of bone or tortoiseshell. The pañolito (small handkerchief) was a Western addition, but the most coveted pieces were made of beautifully embroidered piña cloth from the Philippines. Altogether, these accoutrements harmoniously conveyed the cosmopolitan lifestyle of the Filipino elite in the 19th century (4).

While the forms of Western dress were adapted by the traje de mestiza, undergarments with rigid structures did not gain traction in the Philippines, or in other parts of Asia. Corsets and stomachers stiffened by whalebone or metal, crinolines with rigid hoops, and bustles to exaggerate the bottom were necessary understructures in the West to achieve desired body shapes. However, “these ladies never deform themselves by wearing ‘bustles’; nothing being more beautiful than their natural shape.”6 Instead, women used layers of enaguas, or petticoats, to prop up the sayas and a stiff, locally woven sinamay (a type of abaca cloth) facing underneath the hemline to maintain the desired shape.

By the mid to late 19th century, the saya flared. The Mestiza Española lithograph by Baltasar Giraudier in 1859 shows a woman dressed in saya suelta, displaying a voluminous bell-shaped skirt without a tapis to suppress its fullness (5). Conversely, his India Elegante illustrates a woman of indigenous ethnicity wearing a striped tapis enveloping the upper half of her voluminous saya, which then explodes beneath in multicoloured bands (6). The latter is also reminiscent of Feodor Jagor’s description in 1875 of how mestizas “… are wrapped in a brightly-striped cloth which falls in broad folds and which, as far as the knee, is so closely drawn around the figure [by the tapis], that the rich and variegated folds of the saya burst forth beneath it like blossoms of pomegranate”.7

As early as the 1870s, photos of mestizas reveal the increasing popularity of matching the embroidery of the camisa and pañuelo (7). These carefully co-ordinated pieces were called ternos bordados. According to La Ilustracion Filipina, cloth vendors “… created and continue to create the everchanging fashion of matching embroideries in camisas and pañuelos of piña for the trajes de mestiza, of a thousand fancies and complex designs, imitating the foliage and flowers of the rich and abundant plant life”.8

The sleeves of the camisa also widen like the pagoda shaped sleeves of dresses in the mid-Victorian period. Based on its widespread use throughout the second half of the 1800s, the mestizas and indias took a liking to this sleeve shape, which emanates a more gossamer appearance and is suitable for the hot weather (8). The shape was retained until the 1890s, when the leg-of-mutton sleeve was introduced in the West. Thereafter, shoulder lines dropped a few inches, while sleeves inflated thanks to a good dose of starch. This crisp outline is most evident in Juan Luna’s 1895 painting of the Una Bulaqueña.9

The influx of fashion trends accelerated with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which allowed ships to travel from Europe to the Philippines in a much shorter period. For instance, skirt styles from the West were adapted: the bustle skirts of the 1870s — supported by a padded undergarment to create volume at the back of the waist — were approximated by the backward thrust of sayas de cola, or skirts with tails or trains in the 1880s. The draped overskirts found in Western fashion from the 1870s to the 1880s are suggested by the dalantal — an elaborately embellished apron that also resembles an upscale tapis (9).

By the 1890s, a national consciousness had evolved amongst Filipinos of all social classes. The iconography of the Motherland, or Inang Bayan, was dressed in the traje with colours of the Philippine flag. After the revolution of 1896 and independence from Spain in 1898, the United States annexed the country, spurring war, sweeping changes and the further evolution of the Philippine dress.

Vistas y Typos de Filipinas, circa 1870s–1880s, albumen

print, 13.5 x 10 cm. Lopez Museum and Library Collection

The Rural and the Urban (1900s–early 1940s)

The Americans introduced rapid change, including the widespread use of English, supplanting the Spanish language as the medium of instruction. 600 teachers arrived on board the USS Thomas, tasked with overhauling the public education system. The female teachers inadvertently brought with them a new mode of dress. The morning glory skirt and the bouffant hairdo, associated with the Gibson Girls, became manifest in the serpentina version of the traje de mestiza during the first decade of the 20th century. Serpentina skirts fit snugly at the waist and flare out dramatically toward the hemline with the help of gores or enormous flounces (10). Although Western in origin, the type of joinery of the upper and lower halves of the skirt assumed local sources of inspiration. Local terms were, in fact, given to these variations, such as zigzag (Rio de Pasig after the winding Pasig River), dove shape (La Paloma), flower shape (camia) and butterfly shape (mariposa). The preferred material was also local. Finely woven sinamay were dyed in brilliant colours to create the serpentina skirts as well as the camisa and pañuelo. The result was a completely matching outfit, a precursor of the terno.

By 1916, as Parisian designers like Paul Poiret popularised more relaxed forms, which did away with corsetry and quoted from Eastern dress traditions, the form of the traje also changed. The skirts deflated and a tongue-shaped train was added. The camisa and pañuelo were still constructed from translucent fabric, albeit in less voluminous form (11). A dark coloured sobrefalda, or sheer overskirt, became a fixture, often embellished with embroidery, lace, silk flowers and beadwork.

As Western dresses shortened and became streamlined to be suitable for dancing to jazz music, the traje de mestiza’s skirt narrowed in the early 1920s. However, the saya kept the cola, or train, which lengthened long enough to be held up by hand or pinned down to the waist (12). The random ruffles on the upper cap of the sleeves were organised into equidistant pleats, allowing the sleeves to flatten and rise a few inches above the shoulder line. A designer named Pacita Longos is credited for introducing this innovation. The overall effect is a more sinuous outline, which perfectly fit the context of the Art Deco period.

The traje de mestiza fully transitioned into the Philippine terno — an outfit made up of matching pieces, including a camisa, pañuelo, saya and sobrefalda. The components used precisely duplicated embroidery, appliqué and careful colour co-ordination between the upper and lower garments (13). Starched cañamazo, a stiff open-weave material from Switzerland, babarahin, a locally woven textile from Batangas, and renggue, a combination of abaca and piña fibres from Aklan, were used for upper garments that demanded rigidity.

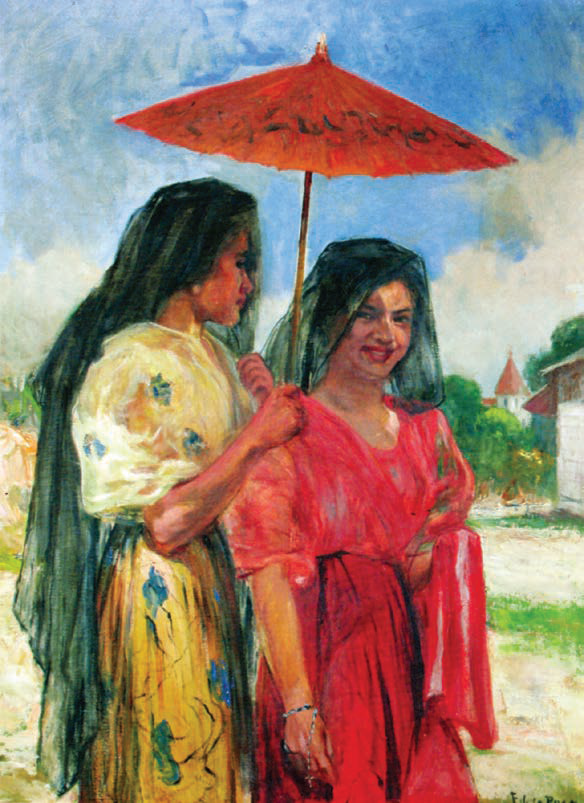

The rapid urbanisation and onslaught of Americanisation caused Filipinos to pine for the idyllic way of life represented by the farming and seaside scenes in the works of the renowned painter, Fernando Amorsolo (14, 15). The antithetic lifestyle found expression in the popularisation of the Balintawak, the rural version of the terno. The basic components of the outfit were almost identical to the terno. However, in lieu of a stiff pañuelo and sobrefalda, a matching alampay (a soft kerchief which also functioned as a scarf) and a tapis were used. The festive colours of the balintawak also eschewed the restraint of the urbane terno. Bold stripes were used on the alampay-tapis combination and prints on sayas often reference tropical flora. Instead of elegant footwear, gaily carved wooden clogs, called bakya, completed the look.

Filipinas in the balintawak posed for studio photos in the 1920s and 1930s (16). They enthusiastically held up Japanese fans, baskets, clay pots, fishing tools and farming implements against painted backdrops depicting quaint rural scenery. The postcard photos were then distributed to friends and family with heartfelt dedications. Other rare occasions for dressing in the balintawak included town fiestas and the annual pilgrimage to the shrine of the Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buenviaje (Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage),10 nestled on top of the hills of scenic Antipolo. However, the visibility of the terno and balintawak belied the rise of the vestido, the more practical Western dress that started supplanting both Philippine dresses. Modern city life and the emergence of Filipina women from their traditional roles in society inadvertently skewed the future of Philippine fashion to the vestido’s favour. While the older generation generally adhered to the tradition of wearing the terno, the young favoured the vestido (17).

53 x 44.5 cm. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection

The New and Old Guard (the late 1940s–1960s)

As early as the 1930s, the zipper allowed designers to create a “one-piece” terno that conjoined the bodice and skirt. This innovation carried over to the 1940s, when practicality ruled. The reality of the Second World War caused Filipinos to give up frivolities. The cola of the terno became an early casualty of the necessity to simplify lifestyles. While the country suffered from the incalculable devastation wrought by the war, the terno was either kept in camphor chests or its materials were recycled as garments for family members. After the country was liberated by Allied forces in 1945 and the Philippines gained its independence, a sense of jubilation swept the nation, with the terno slowly resurfacing. The moment became an opportune time for the young to discard the pañuelo for good. The fichu, which obscured visibility of the breasts, had already become a vestigial accessory cumbersome for younger Filipinas. Designers, led by Ramon Valera, created ternos minus the pañuelo, effectively using the decolletage as a fixture of the contemporary version of the dress (18).

The shift was met with outrage by the older generation, who saw the pañuelo-less terno as a desecration of the national dress. While the young wore these pañuelo-less creations to social gatherings, the old clung to their complete terno ensemble. However, the wishes of the older generation still prevailed in the matter of formal wedding attire. Terno-clad brides were still expected to wear the pañuelo up to the 1950s, to conform to the traditional image of purity and modesty, signified by donning the pañuelo.

terno, circa 1947, contact print, 13.5 x 10 cm. Lopez Museum and Library Collection

The 1950s also provided the ideal environment for designers to experiment with form. Salvacion Lim and Ramon Valera led the creation of couture versions of the terno that primarily experimented with skirt shapes (19). They also kept the gossamer butterfly sleeves unaltered (20), or at least until they started covering sleeves completely with the predominant textile of the dress (21). Annual balls, such as the Kahirup of the Negrense “sugar barons” and the Mancomunidad Pampangueña of the landed Kapampangan families, still required attendees to wear the national dress. They also served as battlegrounds for society matrons to outdo one another in style, to the delight of the press and fashion observers in this so-called Golden Age of High Fashion in the Philippines (22, 23).

By the end of the 1950s, the terno was produced in a myriad of shapes, including the sheath, bubble, mermaid and bouffant forms, which led scholars to remark how “… the terno hewed closely to the latest fashion styles abroad, to the extent that the prevailing European silhouette became a terno merely through the addition of the butterfly sleeves”.11

1958, oil on canvas, 84 x 64 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of Leon Gallery

High Brow and Low Brow (1970s–1980s)

As the vestido has dominated everyday wear in recent decades, the terno was relegated to formal wear. A few stragglers, who mostly continued to wear the terno, included former First Ladies, wives of politicians and prominent society women. Imelda Marcos was no exception, dressed in full-length ternos as day and evening wear. After Ramon Valera’s beaded ternos and draped gowns (1960s–early 1970s), Christian Espiritu (1970s) and Joe Salazar (late 1970s to the early 1980s) focused on embroidery work.

By the 1970s, more Filipinas wore trousers and casual wear following global trends. The terno was hardly ever seen in daily life, other than at Catholic church activities attended by elderly women. Conversely, the privileged few wore exquisite ternos created by couturiers to formal gatherings and state functions. Activities organised by the Malacañang Palace and the high society “Blue Ladies” also created a microclimate that pushed Filipino fashion designers to create and vie for the attention of these extravagant clientele. The scenario was largely responsible for inducing a second Golden Age in Philippine Fashion, producing another generation of extremely talented designers.

However, the chasm between the terno couture-clad elite and the rest of the casually clothed population widened. Whereas Philippine dress was worn by all social classes until the first half the 20th century, the 1970s somehow skewed the perception of the terno as aristocratic dress and costume. As a direct result of this association, plus the relatively high cost of making a terno vis-à-vis Western attire, the use of Philippine dress by the wider population declined even further.

The migration of wealthy families to urban centres caused many town festivities, traditionally organised and attended by the landed gentry, to become the responsibility of the middle and lower classes.12 On rare occasions, a poor family would save up and splurge on a dress for their very own sagala — a maiden in costume joining the Lenten procession, Flores de Mayo13 or Santacruzan.14 The girl is bedecked in a fantastical version of the terno, typically sequined and built like a bouffant dress fit for a princess. It is an ephemeral display of extravagance for all the neighbours to see. It is also an aspiration, which mires the family in debt or subsistence on a diet of rice and dried fish for the succeeding months.

After the EDSA Revolution of 1986, most women followed the lead of President Corazon Aquino not to wear the terno, which had become associated with former First Lady Imelda Marcos. As the first female commander-in chief of the male-dominated Philippine military and bureaucracy, Aquino wore suits and feminine versions of the barong — considered the male counterpart of the Philippine dress. On special occasions, which called for Filipiniana — a hypernym for clothes inspired by the wide spectrum of Philippine dress traditions — Aquino wore embroidered baro’t saya in the manner of the earlier “peasant” versions of the Philippine dress. An era of restraint commenced, and the terno as well as Philippine high fashion entered a period of hibernation.

The National and Global (1990s–2020s)

Sporadic efforts to revive interest in the Philippine dress sprouted in the 1990s. For instance, the artist, Gilda Cordero Fernando, produced Jamming On An Old Saya in 1995. The project combined a publication and a live theatre event, which gathered designers and artists from various fields in a collaborative venture to fashion discarded pieces of terno into new garments. It is a pioneering effort at the idea of “upcycling” and one which blurred the line between fashion show and performance art. The terno designs of Steve de Leon, in particular, mirror the ethos of the global grunge fashion trend and the distinct aesthetics of avantgarde Japanese designers, such as Rei Kawakubo. By then, the terno’s design language was no longer limited to quotations from Western fashion nor the imitation of minute graphic motifs from the East. It now responds to the larger sphere of world culture.

The conundrum of making the terno resonate in the 21st century for a new generation of Filipinas, who are accustomed to global fashion trends, vis-à-vis the desire to keep the Filipino “identity” of the garment became more apparent in the 2010s (24). Terno sleeve sizes, created by relatively young designers, have shrunk to miniscule proportions, which Inno Sotto, the veteran designer, derisively called “teacup” sleeves. The rationale behind the shrinkage could only be ascribed to the tokenism in wearing the national dress while trying not to make it look obviously like the Philippine terno. It is a half-hearted gesture, deeply rooted in the desire to mask national identity and tragically resulting in a generic garment with puff sleeves.

Before the sleeves shrink further and eventually disappear, the phenomenon needs confrontation simply because the butterfly sleeves are the last bastion of the Philippine dress, having lost all its other components in less than a century. Ternocon — a biennial terno-making contest and competition — is one such movement designed to address the issues surrounding the Philippine dress. During its initial edition, JC Buendia, the designer, addressed the issues of wearability and practicality by reintroducing the concept of matching “separates” — the principle behind the terno until the late 1930s. The simple solution spawned casual terno tops, which flooded the ready-to-wear market, making the garment more accessible to a wider demographic of Filipinas.

Len Cabili, who is largely responsible for introducing “slow fashion” in the Philippines and heightening awareness of indigenous dress traditions, also participated in the 2018 edition of Ternocon. In her collection called Talang Silangan (Southern Star), she conjured indigenous textiles, surface decoration and motifs from the northern to the southern Philippines in the creation of contemporary ternos (25). The trailblazing effort also encouraged ready-to-wear designers to use locally woven textiles, such as inabel from Ilocos and inaul from Maguindanao, to make ternos.

On the other hand, Cary Santiago capped the presentation with his “Aviary” collection, referencing winged creatures. Employing sophisticated fabric manipulation and couture techniques, Santiago presented sculptural pieces that elevated the national dress to a reverential sphere. Apart from the butterfly sleeves, the references and construction techniques are not necessarily tied down to local traditions, but they certainly serve as testament to what Filipino craftspeople can achieve in terms of international high fashion standards.

The wide range of contemporary ternos affirms an approach that doesn’t look at binary opposition as mere contradictory forces, which are often reduced to the “us vs. them” construct. Instead of clear delineations of polarities, that are usually drawn to distil the “pure” Filipino identity (e.g. the tendency to view “indigenous” culture as the only legitimate Filipino culture, while demonising Hispano-Filipino influences),15 we see harmonious visual representations of the diversity of cultural influences on the terno and, ultimately, the Filipino. The indigenous, foreign, Oriental, Occidental, rural, urban, highbrow, lowbrow are one. The national is also global.

These efforts in the late 2010s also boosted an ascendance of the terno, encouraging a younger generation and a wider demographic to wear it with self-confidence and pride. Although in its current form it is not necessarily a “dress” or “gown” with butterfly sleeves, but an evolving garment that continues to synthesise the so-called polarities in Philippine life.

1 Zialcita, Fernando Nakpil, Authentic Though Not Exotic: Essays on Filipino Identity, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2005, p. 21.

2 Scott, William Henry, Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, pp. 28–31.

3 Alcina, Francisco Ignacio, History of the Bisayan People in the Philippine Islands, Vol. 2, translated, edited and annotated by Cantius J. Kobak, OFM, and Lucio Gutiérrez, OP, Manila: UST Publishing House, 2004, p. 117.

4 Alcina, 2004, p. 123.

5 Castro, Sandra, Textiles in the Philippine Colonial Landscape: A Lexicon and Historical Survey, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2018, p. 66.

6 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Art & Architecture Collection, The New York Public Library, “Mestiza”, New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-8917-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed September 22nd, 2021).

7 Jagor, Fedor, Travels in the Philippines, London: Chapman and Hall, 1875, pp. 25–26.

8 Boni., “La Sinamayera”, La Ilustracion Filipina, Año II, no. 40 (28 de Agosto de 1892), p. 319.

9 Villegas, Ramon N., “Juan Luna: Filipino Painter and Patriot”, in Arts of Asia, Vol. 34, no. 3, p. 81, fig. 26.

10 Nuestra Senora de la Paz y Buenviaje (Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage) is “a 17th-centuy Roman Catholic wooden image of the Blessed Virgin Mary venerated in the Philippines. The image, a Black Madonna that represents the Immaculate Conception, is enshrined in Antipolo Cathedral in the Sierra Madre mountains east of Metro Manila.” Wikipedia, “Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Our_Lady_of_Peace_and_Good_Voyage (accessed September 22nd, 2021).

11 Bernal, Salvador F. and Georgina R. Encanto, Patterns for the Filipino Dress: From the Traje de Mestiza to the Terno 1890s–1960s, Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1992, p.23.

12 Tiongson, Nicanor G., “Flores de Mayo”, in Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, Vol. 10, edited by Alfredo R. Roces, Manila: Lahing

Pilipino Publishing Inc., 1977, p. 2352.

13 Flores de Mayo (Flowers of May) is a Roman Catholic festival held in the month of May in honour of the Virgin Mary. It involves flower offerings given by girls in fancy dress.

14 Santacruzan (from the Spanish santa cruz or “holy cross”) “is the ritual pageant held on the last day of the Flores de Mayo. It honours the finding of the True Cross by Helena of Constantinople (known as Reyna Elena) and Constantine the Great.” Wikipedia, “Flores de Mayo”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flores_de_Mayo (accessed Sepember 22nd, 2021).

15 Zialcita, Fernando Nakpil, Authentic Though Not Exotic: Essays on Filipino Identity, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2005, pp. 11–18.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift