FRANCES WOOD

OFFERING LECTURES, small “handling sessions” of ceramics where members can present items from their collections for comment, tours of up to twenty-five to see significant sites and collections all over the world (1, 2), and annual newsletters, as well as the long-established annual Transactions—has the Oriental Ceramic Society (OCS) finally, in its centenary year, found the solution to size? From a strictly limited group of a dozen collectors, who met for a decade in each other’s houses (3, 5, 6), the Society has grown to a substantial membership of some 700, almost half of whom live outside the United Kingdom. Despite resistance to expansion in the early 1930s, it seems that most of the Society’s fundamental objectives have managed to survive and thrive.

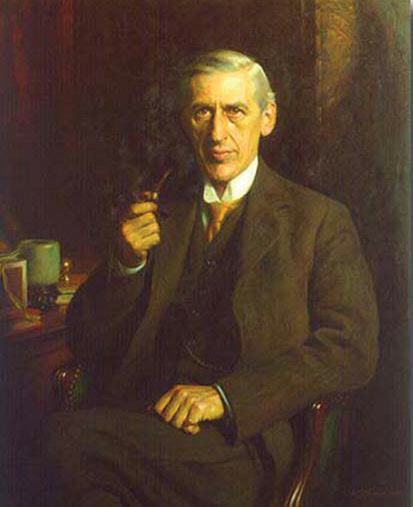

Founded in 1921 by twelve interested parties, predominantly collectors but including three museum curators, membership quickly expanded to a strict limit of fifteen; and the Oriental Ceramic Society was established, in the words of its first Secretary, A.L. Hetherington (4), “to form a little Society at the meetings of which new acquisitions might be discussed”. Hetherington gave an account of the founding of the Society in Transactions 23 (1947–1948) in which, having surveyed the room, he felt free to announce that only he and Bernard Rackham survived out of the original twelve, and that its inception was his inspiration, having “sounded various leaders such as George Eumorfopoulos, Oscar Raphael, Stephen Winkworth…R.L. Hobson at the British Museum and Bernard Rackham at the Victoria and Albert Museum” about founding a society. Sir Harry Garner, in his obituary of the Bluett brothers in Transactions 35 (1963–1964), ascribed “the Society’s inception to a discussion between A.L. Hetherington and Lionel Bluett”. Collectors may have met in Bluetts’, which was described as having a club-like atmosphere, and that was clearly something for which they felt the need.

Hetherington described the mood amongst collectors in the early decades of the 20th century when “Tang mortuary wares” were “brought to light by railway cuttings. These were at first regarded with some scepticism, for prior to the beginning of the twentieth century the Tang wares were known only through the literature. But it was soon clear that these wares were of that date and George Eumorfopoulos was instrumental in getting a number of specimens to this country.” Although the publicly published Transactions included descriptions, and often photographs, of some specimens brought to meetings by members, the minutes of OCS meetings include more details of specimens between the records of business. Indeed, the Transactions give a somewhat limited picture of the Society’s activities, with most space given to the publication of the three or four formal lectures that were delivered each year. As the Society met every month, except August, the other seven or eight meetings were entirely devoted to informal discussion of specimens brought by members, sometimes on behalf of their friends. R.L. Hobson often brought newly acquired items from the British Museum, or items he proposed to acquire, but Eumorfopoulos brought the greatest number of specimens, sometimes showing items belonging to other collectors, such as a peach-shaped water dropper that he brought along in 1925. This came from the collection of the Crown Prince of Sweden, subsequently King Gustav VI, who was made an Honorary Member in 1925 and became Patron of the OCS in 1959.

The record of specimens brought to the very first meeting in 1921 included Thomas Torrance’s shallow bowl from a Ming (1368–1644) tomb in Sichuan, shown by R.L. Hobson “before it was added to the collection of the British Museum”, a “white vase of doubtful date” from Oscar Raphael, who also showed a kiln waster from Yuzhou “before it had been accepted by the British Museum as a gift from K.K. Chow”, of which it was recorded: “If a Song date could be established…an important document would be recorded, but it is probable that the specimen dates from the early days of the Ming.” F.M. Schiller’s “green glazed vase, in the form of a bronze”, was thought by “one Chinese connoisseur” to be a Song (960–1279) imperial piece “though according to European opinion it bears a close resemblance to a Yungcheng product of Ching- te- chen…the specimen may be an imperial Ming piece…” A bowl of “Ting type of a doubtful date” was dismissed as an example of “modern copies made possibly at a factory near Peking. They resemble in many respects and with varying degrees of likeness, the Ting yao of the Sung dynasty but…” There were differences of opinion: Hetherington wrote that “it was generally agreed that Eumo was the best judge of a specimen, although Hobson was easily the most learned on the subject”.

It is worth noting, too, that the Transactions, with their detailed descriptions and photographs, immediately excited interest abroad. In the first issue, a bowl belonging to H.B. Harris was shown, with an inscription which, as reported in Transactions 3 (1923–1924), provoked the most distinguished French scholar, Paul Pelliot, to write an article in T’oung-Pao (XXII, 1923) asking “Mais Tsiang-K’i etait-il potier?” In Transactions 2 (1922–1923), founder-member Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Dingwall showed a Nabeshima plate with marks suggesting that it had once been in the collection of Augustus the Strong and in Transactions 3, it was reported that Dr Zimmerman of the Dresden Museum had been in touch, correcting some assumptions about Augustus’ acquisition of the plate. These reactions from leading scholars in Europe demonstrated the very real interest in the subject and the significant contribution of the OCS to broadening knowledge.

The freedom to question and argue about specimens with friends was clearly a matter of great importance to the Society’s members and the genial, friendly club-like atmosphere of meetings is reflected in F.N. Schiller’s satirical paper, “The Quest for the Purple Ting” (delivered on June 20th, 1925). He began by blaming Harry Oppenheim for the content and he jokingly described purple Ting as being “elusive as the Snark”. The paper derived from depictions and descriptions in the album purported to be by Hsiang Yuanpian/Xiang Yuanbian (1525–1590), published in facsimile by Dr S.W. Bushell in 1908 and, at the time Schiller was writing, one of the few translated works on Chinese ceramics.

Purple Ting continued to preoccupy the OCS. At the meeting on March 2nd, 1932, the minutes record that Mr Barlow showed “a Ting type bowl which only differed from a white Ting bowl in that it was covered with a brown glaze of a deep café-au-lait colour. Its introducer in language in which assurance was subtly blended with diffidence sought to persuade the Society that the piece in question might be purple Ting, urging that the description in Hsiang’s album ought not to be taken too literally as it was a well-known fact that purple grapes that had passed their prime were distinctly brown of hue and that once this colour glaze was accepted the mystery of the disappearance of purple Ting ceased to exist. Mr Yetts supported this view by pointing out that the original drawings in the album had been in outline only and that the colours were a subsequent addition, and that the Chinese word for purple [tzu/zi 紫] like other colour descriptions in Chinese was ambiguous, and could be translated as either purple or brown. Professor Collie upheld the accuracy of Hsiang’s description, and urged that whatever doubts might be cast on the colour of ‘the ripe grapes’ there could be none with regard to that of the aubergine plant to which the pieces illustrated in Hsiang were compared in more than one passage in the Album. Sir Herbert Jackson pointed out that the predominance of purple in a manganese glaze resulted from potash in the feldspar, and that a substitution of soda for potash would result in a brown colour, and that the composition of the glaze could be determined by chemical analysis. After some further discussion the view prevailed that a definite judgement could only be formed after seeing the bowl in daylight, and subject to chemical analysis, which it was hoped the owner would allow Sir Herbert Jackson to make.”

At the next meeting of the Society on April 6th, 1932, in E.B. Hoare’s house, the discussion continued, involving science, translation and perception of colour, when “a report of this bowl received from Sir Herbert Jackson was read to the effect that the glaze contained neither lead nor manganese, though a close analysis might show a trace of manganese, but not enough to account for the colour or to suggest that it was deliberately introduced. Examination of the bowl by chemical analysis and under the lens showed that plenty of iron was present and the colour appeared to be due to iron. And that in so far as the glaze showed any purple tinge in daylight, it appeared to be due to iridescence due to the deterioration of the glaze, which when examined under the lens was brown and red.

There followed a general discussion which turned largely on the point whether Hsiang’s translators in translating tzu by purple had accurately described the colour of the pieces that he saw, and it was argued that there could be no certainty on the point as if Hsiang had looked on a grape when it was brown he would still have described the colour as tzu. The President was of the view that the pieces seen by Hsiang were undoubtedly purple but they weren’t Ting. As regards the bowl the general sense of the meeting was that whatever it was, it wasn’t purple Ting. One certain fact emerged from the discussion that the most elusive of Chinese ceramics had once more eluded definition.”

Only eighteen months later, Sir Percival David gave a lecture to the newly constituted and expanded OCS, at a meeting held on December 8th, 1933 in the Courtauld Institute. He spoke on “Hsiang and his album”, and after careful examination of many manuscripts and copies and reference to other sources, objects and illustrations, pronounced the commonly consulted edition of the album an 18th century fake or compilation from a multitude of sources. He thus put an end to the sometimes facetious, sometimes serious, debate about purple Ting, “much ado about next to nothing” in his view, and with an immensely erudite lecture effectively inaugurated a more scholarly era in the history of the Society.

David’s lecture was based on bibliographical research and marked a departure, but the enthusiasm for scientific research into glazes had been a strong feature of the OCS since the beginning. Professor Collie (7), a founding member of the Society and Professor of Organic Chemistry at University College London, gave a paper that appeared in the very first edition of the Society’s Transactions, “A Monograph on Copper Red Glazes”, followed by “A Plea for Lead Glazes of the Sung” in 1926. Sir Herbert Jackson (8), Professor of Organic Chemistry at King’s College London, was invited to join the debate about copper red, and soon followed with “The Iridescence on Early Chinese Lead Glazes” (1924) and further articles. Both were keen participants at specimen meetings, showing their own acquisitions and commenting on others. Sir Herbert Jackson could hardly wait to work on Mr Barlow’s purple or brown bowl and in 1931, when Eumorfopoulos brought for discussion a colour photograph of a bowl in the Hallwyl Collection in Stockholm obtained by Orvar Karlbeck from railway work in Henan, a “waster, a Zhou freak” with a lustrous metallic deposit, Sir Herbert “wanted to examine it microscopically before committing himself”. Professor Collie was similarly inclined, as was the long-term OCS Secretary, A.L. Hetherington, who had served as Principal of the Government Collegiate School in Rangoon (Yangon) and as Assistant Director of Public Instruction, Burma, before joining the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. Hetherington published Chinese Ceramic Glazes in 1937, and on October 13th the same year, addressed the Society on the subject of “The Why and Wherefore of Chinese Crackle”. Despite the fact that the Society had recently expanded and the meeting was held at Lancaster House rather than in a member’s house, as had been the earlier custom, Hetherington adopted the same jocular tone as Ferdinand Schiller had in his quest for the Purple Ting. Deploring the lack of interest in science, Hetherington remarked that in many schools, “the stinks master was often treated in much the same way as the unfortunate foreigner who was detailed to teach French”.

At the 106th meeting on October 7th, 1931 held at Sir Neill Malcolm’s house, Hetherington’s contribution was worthy of a science master, for he “showed the Society a small experimental glaze made by the Vyzes, the red colour of which was entirely due to the accidental inclusion of a halfpenny among certain wood shavings that had been burnt to obtain wood ash for the glaze. The halfpenny had not been visibly damaged by the fire and it was remarkable that the infinitesimal amount of copper dispersed in the ash had caused the pronounced colour. This led to an interesting discussion on the possible use of old bronze as a Chinese source of copper supply for glazes to which Sir Herbert Jackson and Mr Yetts contributed.”

Sir Herbert and other scientifically minded members were keen to improve examination of specimens which, up to this point, were always seen by artificial light, as OCS meetings were held in private houses and in the evening. An unusual arrangement was proposed in October 1930, “if in the opinion of the meeting an object raises doubts which cannot be resolved without examination in daylight, the exhibiting member should deposit the object at the British Museum in Mr. Hobson’s custody for 10 days. During that period any member would be at liberty to study the object and record his view upon it. Thereafter the Editorial Committee would examine it and the views as recorded, and would authorize the Secretary to enter in the Minutes their opinion, together with any other divergent opinion. Should it appear necessary, on the reading of the Minutes, that further discussion was required, the exhibiting member should be asked to bring the specimen to another meeting for the purpose and at such a meeting no guests should be present.” To today’s curators, the idea of depositing objects in a museum and inviting visitors to view them at their convenience is unthinkable, if only from the security point of view, but it is possible that for Hobson, the opportunity to study new finds was a matter of useful experience. It also shows the OCS setting itself up as the authority on Chinese ceramics, determining dates and authenticity.

This self-appointed authority was threatened, however, by the need to transform the Society. The impulse came from two different viewpoints. M.W. Elphinstone wrote a long letter to the President, George Eumorfopoulos, on July 18th, 1932 in which he set out the financial position of the Society, which was precarious, mainly because of the cost of producing the Transactions, and suggested an expansion of membership, noting that this would fall within the “object” of the Society, to “widen appreciation and to acquire knowledge of Eastern Ceramic Art”. The President replied, stating that he had been interested to follow the activities of the Verein für Asiatische Kunst and wondered about transforming the OCS into such an academic body. Eumorfopoulos had considerable contact with the Verein für Asiatische Kunst, as it had organised a large and comprehensive exhibition of Chinese art in 1929, to which Eumorfopoulos had loaned some pieces and which he had visited, together with R.L. Hobson, Percival David, Oscar Raphael and the Crown Prince of Sweden, amongst the 60,000 visitors the exhibition in the Martin-Gropius Bau had attracted. Eumorfopoulos’s loan of his double ram zun (now in the British Museum) attracted the attention of the poet, Florence Ayscough, who wrote Phantasmagoria (1929) about the exhibition in which the animal exhibits spoke to her:

“The rams spoke first, those grave beasts who, standing back to back, support on their pearly haunches the vessel which once held sacred spirit made from grain.”

The German society had been founded in 1926, and from the beginning had been closely associated with the Museum of Asian Art. Its main activities had been to organise large exhibitions of Japanese and Chinese art, although by 1930 it had a membership of some 3000. It was in many ways very different from the OCS. However, the idea of expansion into a broader membership, whether for academic or financial reasons, was put to the OCS members in the summer of 1932 and debated through the autumn. On October 5th, 1932 at a meeting in the President’s house on the Embankment, Eumorfopoulos “expressed his own views that the time had come owing to the difficulties inherent in the financial position of a Society as small as the OCS, and the fact that owing to the growth of public interest in ceramics the Society had become a body of some importance with a reputation extending beyond the boundaries of its birthplace…” There followed “an animated discussion in which a great variety of views were expressed, the larger number of those present seemed to favour some form of expansion”.

At the next meeting on December 14th, 1932 in Mr Oppenheim’s house, a report (produced by Eumorfopoulos, Percival David, R.L. Hobson and M.W. Elphinstone) was discussed. “The essential feature of the report was an endeavour to support arrangements whereby the sphere of usefulness could be widened, the finances of the Society be placed on a sounder footing while still preserving the intimate nature of the meetings and deliberations of present members. To this end it was proposed to organise three open meetings a year at some convenient institution at which papers would be read to a wider circle than the present membership. Associate members might be admitted at a subscription which would carry with it the privilege of attending these open meetings and to receive a copy of the Transactions. The museums and libraries at present in receipt of free copies of the Transactions would be asked to subscribe for them in future…”

The proposal to set up separate types of membership was quickly rejected and at the next meeting on January 11th, 1933, it was agreed that “there should be one class of membership only”, but that “a private club consisting in the first instance of the members of the present Society should be formed with its own set of rules during the first year of the enlarged Society’s existence, as an appendage to but not a constituent part of the enlarged Society”.

On June 7th, 1933 at what was called the “123rd and last” meeting of the Society held at Mr Russell’s house, the first meeting of the new, enlarged Society was fixed for October 4th at the Courtauld Institute when Percival David and R.L. Hobson would read a joint paper entitled “Blue and White in the Seraglio”. Appropriately, the rest of the meeting was devoted to voting in twenty-two new members to serve as the basis for expansion.

A “private club” for the original members was indeed set up and met throughout the 1930s. The inaugural meeting of the Dragons Club was held on January 3rd, 1934 at Mr Raphael’s flat where it was proposed that it be limited to eighteen members and meet at a member’s house three times a year “to discuss informally matters of Oriental Ceramic interest and to display specimens of interest”. Of the eighteen members, nine had been founding members of the OCS. Just as with the original Society, they continued to meet in members’ houses, the number of members limited to those who could be comfortably accommodated in a private drawing room. However, on October 3rd, 1939, a month after the outbreak of the Second World War, the President, George Eumofopoulos, wrote to the Secretary, A.L. Hetherington: “I agree that for the time being the Dragons’ meetings should be disbanded. As for the OCS we shall attempt to carry on with the daylight meetings.” The Dragons never met again, for by the end of the war, Eumorfopoulos, Hobson and Raphael had all died and the core of the informal interest of the private club had gone with them.

The expanded and more open OCS continued to flourish, with 270 members by 1947 and a renewed interest in creating exhibitions. Although senior members of the OCS had been largely responsible for the great “Chinese Exhibition” of 1935–1936, which had greatly increased public interest in the subject, after the war with the lease of part of Bluett’s basement and its open-fronted cabinets, the Society began once again to organise its own small exhibitions of items from members’ collections, starting with Ming blue and white from October to December 1946. After a decade of these small exhibitions, the Society began to collaborate with the Arts Council, arranging larger exhibitions (without the open-fronted cabinets) on the arts of the Ming (1957), the Song (1960) and the Qing (1964).

Frequently worried about money, with the cost of producing the Transactions, the need for an office to support the enlarged Society and the expenditure on exhibitions (which reached a crisis with “Porcelain for Palaces” in 1990 as the sponsor lost interest and transportation and packing costs rose), the Society was forced to launch a number of fund-raising appeals during the post-war period and, thanks to the generosity of members, all was not lost. Recent decades have seen a great change in activities with more emphasis on contact with China, which had been so difficult in the early years. OCS trips were organised, the Chinese translation series started, and the Chinese Scholars Fund set up to invite ceramic specialists and archaeologists to lecture in the UK.

The OCS today, with its broad membership including students, collectors, specialists and amateurs, is very different from the select group of distinguished collectors who first met in 1921. But their aims, to find out more about Chinese ceramics (9, 10), to open the field, to share and exhibit, are still alive.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift