LAN MORGAN

Assistant Curator, Peabody Essex Museum

UNDER AN ORDINANCE adopted by the city of Salem in 1839, George Peabody, ship owner and financier, de-signed the city’s first official seal. Much the same today, the seal bears the motto: “Divitis Indiae usque ad ultimum sinum” (“To the farthest port of the rich East”). Salem’s Golden Age of maritime navigation was waning by the mid-19th century, but nonetheless, its connection to Asia was solidified. The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), America’s longest continuously operating museum, was established by Salem’s merchants and shaped by its citizens. The institution’s identity is as much rooted in Salem as it is in the Asian countries across the globe with whom Salem made contact through maritime trade. Some of the first objects brought back for the collection were from Asia, setting the stage for over 200 years of collecting that continues today. While the later articles in this issue of Arts of Asia will delve more deeply into the museum collections and new installations, this article serves to provide an overview of PEM’s historical connections with Asia, while broadly highlighting areas of PEM’s exemplary Asian collections.

The city of Salem is situated on the northern coast of Massachusetts, a location important for its access to the sea. For thousands of years, the region nurtured generations of indigenous communities, including the Pawtucket, Pennacook, Massachusett and Wampanoag. In 1626, European colonists settled the area now known as Salem, deriving its name from the Hebrew word for peace. Inhabitants of the town made ample use of Salem’s coastal location, first establishing a fishing industry and quickly turning to lucrative maritime trade. By the close of the American Revolution, Salem was well positioned to take advantage of unrestricted trade and forge new commercial relationships. Investing huge sums into expanded fleets, Salem’s entrepreneurial citizens were some of the first Americans to reach Asia and the East Indies. They returned to Salem with rich commodities to sell, such as spices, tea, textiles and porcelain, as well as “curiosities” to share with their friends and loved ones. These endeavours not only made Salem’s mariners and investors exponentially rich, but uniquely connected them to Asian cultures and societies far outside of Salem’s borders.

Against this backdrop, PEM’s origins began in 1799 when twenty-two Salemites established the East India Marine Society. From its inception, the Society set both intellectual and benevolent objectives. Membership was limited to sea captains and supercargoes who had navigated near or beyond the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn, underscoring the organisation’s emphasis on advancing navigational knowledge. In addition to raising funds to financially support the families of deceased mariners members were tasked with forming a “museum of natural and artificial curiosities”. This spurred a period of nearly seventy years of collecting, as members returned from their travels across the globe with objects specifically procured or commissioned for the collection, and citizens of Salem donated their own objects rich with personal history. In 1824, the society built East India Marine Hall as the museum’s first exhibition space (1). Here, many Americans had their first encounters with Asia through its displays of objects from China, Japan and India, as well as Africa, the Pacific Islands, Latin America and the Caribbean. An Indonesian sculpture of Ganesh, the Hindu elephant god, was embedded above the doorway of East India Marine Hall (2). Known as the lord of auspicious beginnings, Ganesh made a fitting symbol for the museum’s first permanent space.

In 1867, financier George Peabody (a different man from the George Peabody who designed the city seal) funded the creation of a new natural history and anthropology museum, which would eventually absorb East India Marine Hall and its holdings, as well as the natural and ethnographic collections of the Essex Institute, a nearby organisation focused on Essex County history. The organisation was named the Peabody Academy of Science, which it operated under until 1915, when it was renamed the Peabody Museum of Salem. In 1992, it fully merged with the Essex Institute, to become the Peabody Essex Museum. Throughout this history, the separate institutions continued to collect and exhibit both local and internationally collected objects and works of art, building a narrative of Salem’s identity entangled with the cultural and material production of its global counterparts.

By the time East India Marine Hall opened in 1825, India was already established as one of Salem’s most important trading destinations. PEM’s early Indian collections, therefore, not only benefited from the frequent excursions of Salem mariners to India, but also the relationships they forged as they conducted business. Banians, an elite class of Indian merchants specialising in the American market, were an important connection for American merchants in India. These essential intermediaries instructed American merchants in regional customs and the inner workings of local business. Raj Kissen Mitter, a prominent Banian from Kolkata (Calcutta), maintained a particularly close relationship with New England merchants throughout his lifetime. In 1840, Mitter gave his Boston-based client, John Parker, a life-size likeness of himself made in unfired clay, seated on an Anglo-Indian style chair (3). The exceptionally lifelike sculpture was likely executed by Sri Ram Pal, a celebrated potter-sculptor working in Krishnangar. The commissioning of this figure, intended for display, signals Mitter’s consciousness of the role his image would play in maintaining a connection to his business associates once they had returned home. Parker immediately donated the figure to the Society, where it was displayed with similar life-size and miniature clay figures in East India Marine Hall.

Mitter was not the only Banian to solidify trading relationships through gifts and exchange. Rajinder Dutt, another of Kolkata’s best known Banians, similarly sent likenesses to his clients and gifted objects directly to the Society. In 1850, Dutt donated a three-piece sculpture of Lakshmi (Gajalakshmi), the Hindu goddess of wealth and prosperity (4). This is significant in light of Dutt’s interest in promoting Indian art in America. Dutt was a Western-educated intellectual, whose involvement in cultural affairs led him to advocate for the recognition of Asian art as vital to the burgeoning field of art history.

PEM’s Chinese collections are also singular among American museums as a result of Salem’s early trade. Luxury goods, brought back from early trips to Guangzhou (Canton), richly furnished the homes of Salem’s upper classes and merchant elite, while others came directly into the East India Marine Society’s collections. Lacquered tea caddies, sumptuous silks and personalised porcelain are all embedded with stories linking them to the specific voyages, the interactions and experiences of the merchants who procured them. These collections of Chinese export art, discussed further in Karina Corrigan’s article, affirmed the Society’s identity as an institution at the forefront of entrepreneurship and cultural exchange.

Even after Salem’s maritime industry diminished in the late 19th century, the museum continued to bolster its Chinese collections with objects that expressed both the country’s artistic traditions and its everyday life. Worth noting is an exceptional collection of Chinese textiles, which includes a variety of Qing dynasty court robes, as well as an array of Chinese women’s fashion from the early 20th century. The recent acquisition of Shi Jianmin’s stainless-steel chair sculpture demonstrates PEM’s commitment to celebrating Chinese artists working at the vanguard of contemporary art.

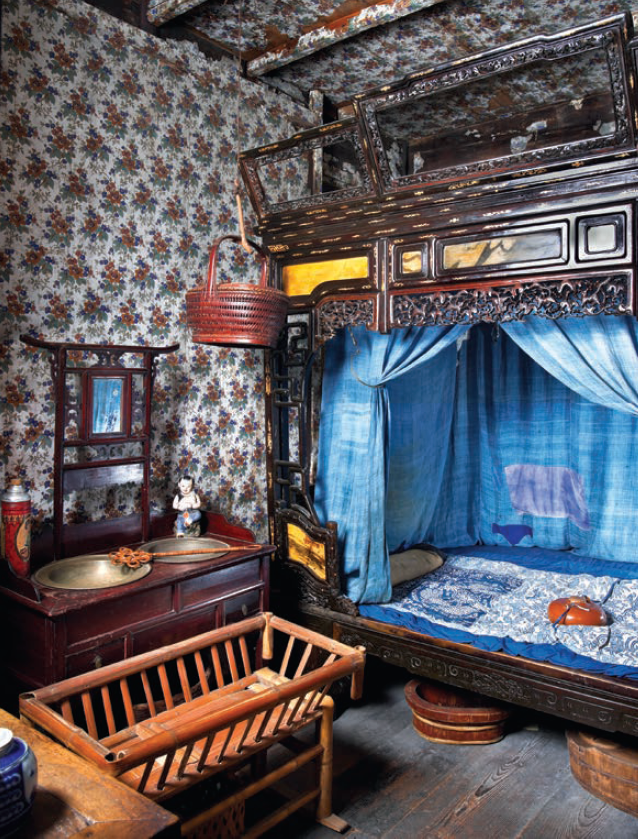

What is the largest, and perhaps the most important, example of Chinese art and culture on PEM’s campus may be found just outside the museum’s main atrium. In 2003, PEM opened the doors to Yin Yu Tang, a 200-year old family home by a merchant in a small village in China’s Anhui province (5). Eight successive generations of the Huang family lived in the home from about 1800 until 1982. Through a cultural exchange with the Chinese government, Yin Yu Tang was carefully documented, disassembled, and transported from China and meticulously re-erected in Salem. For seven years, a team of curators, preservation architects, and traditional Chinese and American craftsmen worked to conserve the home and bring its story to life.

Furnished with objects used and passed down by the Huang family, a visit to Yin Tu Tang feels like a step back in time and a window into rural 20th century Chinese life. Sixteen bedrooms ring a central open-air courtyard, the essential gathering and working space for multiple generations of the family. Posters and chalk graffiti, dating to the 1960s, tell of the shifting political tides of that era. The juxtaposition of traditional and modern, as well as locally-produced and imported domestic objects, reflect China’s global interconnectedness throughout the centuries and bear witness to the sweeping cultural changes the members of the Huang family experienced during their lifetimes (6).

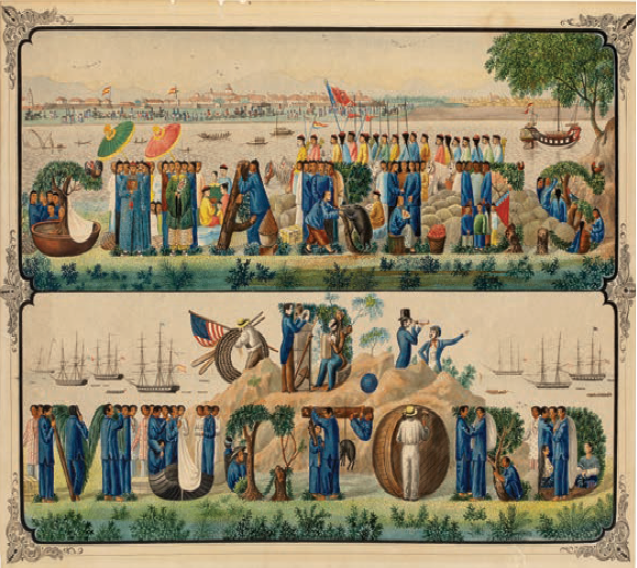

PEM’s unique collection of objects from the Philippines reflects another country’s rich history as a centre for global exchange and Salem’s early involvement in that trade. A very early daguerreotype in the collection, dated September 1850, depicts the Boston trading ship, Reindeer, docked on the River Pasig in Manila (7). Accompanied by a hand-written note on the verso, the ship is described as having lost its masts during a typhoon. This work was donated to the museum by a member of the Mugford family, a Salem merchant clan who made their fortune trading in the Philippines and China. Another member of the same family, Charles D. Mugford, proved his cultural fluency with the Philippines by commissioning a letras y figuras (8). Attributed to José Honorato Lozano, a Filipino artist known for pioneering this type of painting, letras y figuras usually featured a patron’s name formed by a composition of human, animal and plant motifs specific to that client. Mugford’s letras y figuras includes a grouping of Chinese figures forming his first name, and a grouping of Filipino figures forming his surname. His middle initial, “D”, is framed by American figures surveying a harbour and one sailor hauling a roll of hemp cordage. These inclusions allude to Mugford’s business dealings between China and the Philippines, and reference his involvement in co-founding the first steam-powered rope factory in the Philippines.

PEM’s Filipino collection also includes a small, but significant, collection of textiles. Of particular note are several garments and samples made from piña cloth, a textile found only in the Philippines. Made by laboriously extracting fibres from the Spanish Red or Native Philippine Red pineapple, the textile was expensive to produce and exemplary of the luxury goods made for both local consumption and export. A triangular pañuelo (shawl), with scalloped edges and embroidered rosettes, demonstrates the skilled lacework involved in working the cloth (9). Additional Filipino textiles in PEM’s collection, including barongs (sheer men’s shirts) and silk Manila shawls, illustrate the confluence of international influences shaping fashion under Spanish colonial rule.

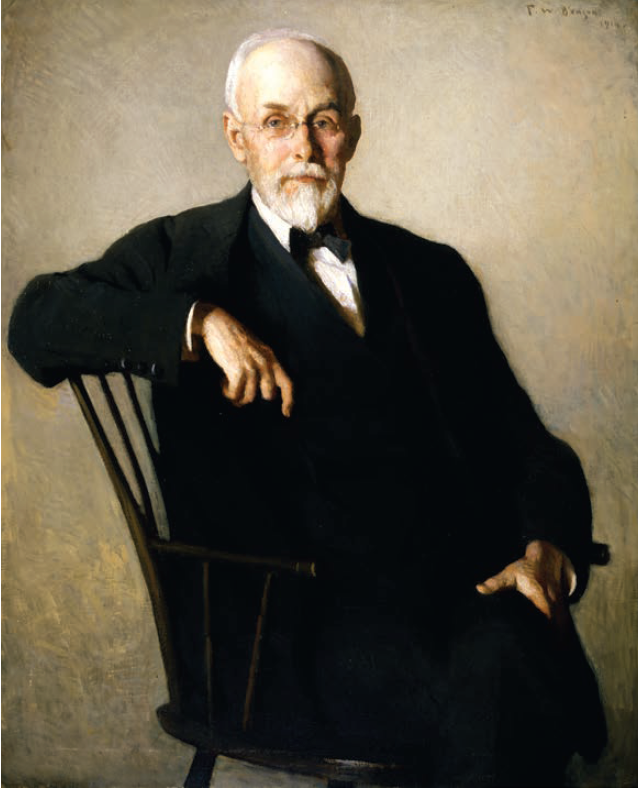

While the foundations of PEM’s Asian holdings were formed by Salem’s mariners, some aspects of the collection reached maturity through the foresight of the museum’s early administrators. In 1867, the Peabody Academy of Science hired Dr Edward Sylvester Morse, a Harvard-trained zoologist with a keen understanding of nascent museology (10). In 1877, just over two decades after Japan opened its borders to foreigners, Morse began one of three extended stays in Japan. While the initial goal of his trip was to study a rare marine invertebrate, he quickly fell in love with the country. He expanded his purpose, carrying out archaeological digs at the Omori shell mounds where he made some of the first discoveries of Japan’s prehistory. Morse’s affinity for Japan’s people, customs, art and architecture also led him to collect everyday domestic tools, food specimens and personal objects for the museum. Today, these quotidian objects not only serve as important evidence of the material life of everyday Japanese people in the Meiji period (1868–1912), but present a window into Morse’s experience as one of the first Western scholars to enter Japan after it opened to travellers.

PEM’s collection of Japanese art continued to grow under Morse and after him, expanding in scope and time period. At his urging, benefactors, such as William Sturgis Bigelow, augmented the museum’s holdings through a series of important donations that bolstered the museum’s late Edo (1603–1867) and Meiji period holdings, as well as objects created for export (11). More recently, acquisitions of important contemporary ceramics from the collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz, such as Yū’s ebullient Furoshiki: Wrapping Cloth, speak to the museum’s ongoing effort to promote contemporary Japanese culture and artistic production. Thanks to these incredible efforts over the past century, PEM’s Japanese collection today is one of the largest and most significant museum collections outside of Japan.

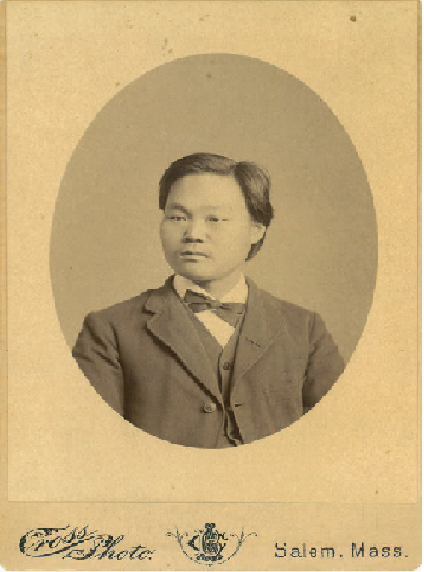

In addition, Morse also pioneered collecting works from Korea, making PEM one of the first American museums to form a Korean collection. This began on Morse’s final trip to Japan in 1882. Soon after, Korea’s first official delegation arrived in the United States in 1883, bringing Yu Giljun (Yu Kil-Chun) to the country (12). After completing his duties in the nation’s capital, Giljun stayed in the Boston area for over a year to study mathematics and science. During this time, he became acquainted with Morse through Percival Lowell, the delegation’s foreign secretary and translator. Giljun soon formed a relationship with Morse and counselled him on the institute’s Korean holdings, including an acquisition of 225 Korean objects collected by Count Paul Georg von Möllendorf, adviser to Korea’s King Gojong (reigned 1863–1907). Before leaving, Morse requested that Giljun donate some of his personal effects. PEM now holds several rare objects from Giljun’s personal collection, including a gat (hat) made from hair, lacquer and bamboo (13).

Morse’s initiative also prompted Boston-area intellectuals and collectors to donate to the Korean collection. The prominent Boston collector Charles Goddard Weld assisted in the purchase of works collected by Gustavus Goward, an American diplomat, who had spent time in Korea. Lowell also donated several objects acquired during his time as a diplomatic missionary in Korea, including a handheld candle lantern, possibly used as a device to bring good fortune during the delivery of babies. The lantern is ornamented with medallions and bats, an auspicious symbol of longevity (14). During this time, the museum also acquired a group of nine rare musical instruments, later exhibited in the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, and outstanding examples of late Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) decorative arts.

In the 1980s, PEM’s Korean art collection was recognised as one of the most important in the United States by a delegation of specialists sponsored by the Korea Foundation. This honour has stimulated further growth and scholarship, and PEM continues to develop its holdings to represent contemporary Korean artists. An important recent gift of a moon jar by the artist, Young Sook Park, celebrates Korea’s long ceramic history. Modelled after moon jars made in the Joseon dynasty, the work can be held in direct conversation with PEM’s exemplary collections of objects acquired during that period (15).

PEM’s institutional history and its connection to Salem provides rich context for its Asian collections, even as they expand. Today, our understanding of the depth of our holdings and their rich capacity for storytelling grows. Partnerships with local and international museums, scholars and educators have provided valuable insight, as well as opportunities to make connections across collections. As we continue to explore our holdings and conceive new exhibitions and installations, PEM’s Asian collections will serve the vital purpose of highlighting Asian art and culture, while also telling the story of how our own national identity has been shaped through our relationship to Asia.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift