GUO FUXIANG

Curator, The Palace Museum, Beijing

Translation by Emily J.C. Tu and James R. Peipert

THE DEVELOPMENT of Chinese jade ware reached its pinnacle during the Qianlong reign (1735–1796) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). This phenomenon was largely attributable to promotion by the royal court, in particular Emperor Qianlong’s personal endorsement. It is worth noting that imperial jade ware of this period bears Emperor Qianlong’s distinctive hallmark, which assumed exquisiteness and elegance as crucial guidelines for jade collecting. No jade object was too small to be crafted by the jade artisans of the Qianlong court, thus setting the stage for novel art forms. The one genre that deserves special attention is the thumb ring made for imperial archers. These small jade ornaments, created for appreciation purposes, were produced in large quantity during the Qianlong period and valued highly. Consequently, the archer’s thumb ring is an excellent reference point for the investigation of Qianlong period jade ware and even the history of jade ware production in the Qing dynasty. This article aims to undertake a comprehensive examination of the history of the archers’ thumb rings in regard to their production, collection and presentation as awards. The social-historical circumstances relating to Emperor Qianlong’s attention to, and control over, the production of imperial jade archers’ rings will also be examined.

Origin

The archer’s ring was called she in ancient China. Xu Shen, the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) etymologist, defined she in his compilation, Shuo Wen Jie Zi (An Explication of Written Characters), as follows: “She, like jue, is an archer’s thumb ring and is used to pull the string of a bow. It is usually made of ivory or tanned leather and is worn on the right thumb.”1 This means it was worn in order to protect the archer’s thumb from injury while pulling the bowstring to shoot an arrow.

In Shi Jing (The Classic of Poetry), there is a stanza from the poem, Wan Lan (A Conceited Lordling), under the Odes of the State of Wei that goes: “O the sparrow-gourd is now in leaf! At the stripling’s waist is an archer’s ring!”2 This explains that during the Shang (circa 1600–1100 BC) and Zhou (circa 1100–256 BC) dynasties, ordinary teenagers, who knew archery or were able to steer a carriage, could wear an archer’s ring; and it also indicates that archers’ rings were prevalent at the time. The preservation of these thumb rings has not been easy because those worn by commoners were predominantly made of leather. Only those made of jade—symbolising authority and status—worn by a few military commanders, have occasionally been discovered in archaeological excavations.

Over time, the function of the she became both practical and ornamental. These decorative collectibles evolved from being practical implements, used in mounted archery, to an integral part of the art of Chinese jade ware, due to the direct advocacy and promotion by the Qianlong emperor.

Height 37.4 cm, width 195.5 cm, Palace Museum Collection, Beijing

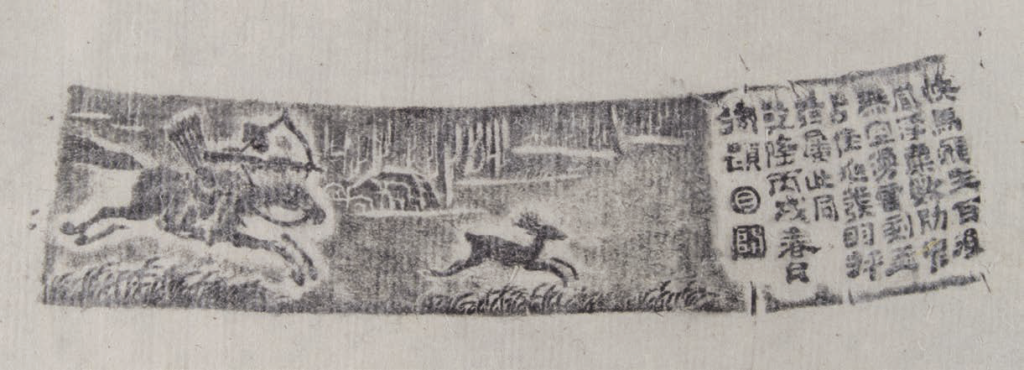

A highly cultivated ruler, Qianlong was well versed in the Chinese zither, Chinese chess, calligraphy, painting, as well as horsemanship and archery. While practising mounted archery, he normally wore a thumb ring made of animal horn or bone. These types of rings can be observed in paintings in the Palace Museum, Beijing, such as Emperor Qianlong in Armour Inspecting the Troops (1, 2) and Taking a Stag with a Mighty Arrow (3, 4). However, it was the jade archers’ rings made for display and appreciation in which the Qianlong emperor showed a keen interest and great passion. As a result, archers’ rings were transformed into elegant objects of high artistic value.

Around Tomb Sweeping Day in 1752, a jade archer’s ring was brought before the Qianlong emperor. Taken by its lustrous quality and exquisite craftsmanship, the emperor was inspired to write a poem titled Yong Yu She (Ode to the Jade Archer’s Ring),3 in which he compared archers’ rings made of ivory and bone with this one made of jade. He deemed that the former “merely pass on their antiquity” while the latter not only “resembles exquisite legendary archaic jade”, but “its virtuous, appealing and trustworthy qualities are to be replicated upon repeated viewings.”

This was Qianlong’s first ode eulogising the archer’s ring, which was later included in scroll 32 of Yu Zhi Shi Er Ji (Imperial Poetry, Volume II) (5). This perspective formed the baseline that he later used to understand and evaluate other jade archers’ rings. From then on, these rings were clearly on his mind: for Qianlong composed no fewer than fifty poems about various examples over the next forty-four years of his reign, demonstrating his passion for these small objects.

When exactly did Qianlong commission the earliest production and what circumstances prompted the making of these rings? If we turn our attention to the informative archives of the Palace Workshops under the Imperial Household Department, we can see that about one year before the first imperial ode to the jade archer’s ring was written, Qianlong had already undertaken a considerable amount of preparatory work for the production of these rings.

An archive entry on May 27th, 1751, stated:

Eunuch Hu Shijie presented: one steamed chestnut-coloured cylindrical jade vase with characters and immortals, wooden stand; one archaic Han dynasty jade cong ritual vessel with a yarrow pattern, wooden stand; one Han jade ribbed circular brush washer, wooden stand; one Han jade beaker vase with chi tiger, wooden stand; one steamed chestnut-coloured jade water dropper with silkworm decoration originally from Qianqing Gong (the Palace of Heavenly Purity); one Han jade circular ornament originally from Qianqing Gong; two stag antler archers’ rings. Imperial decree: have them delivered to the Ruyi Guan (the Wish-Fulfilling Studio) of the Yuanming Yuan (Gardens of Perfect Brightness). Respect this.4

The document does not provide any information about the reason for delivery of these objects. However, two days later, on May 29th, another entry indicated that they were handed over to the Ruyi Guan with a detailed request:

On May 29th of this year, Eunuch Hu Shijie delivered: one stag antler archer’s ring, one small Han jade cong ritual vessel, one Han jade vase of steamed chestnut colour, one Han jade beaker vase with archaic pattern, one Han jade vase with recumbent silkworm and key-fret patterns, one Han jade hand warmer with double-elephant motif and one Han jade beaker vase. Imperial decree: Have the Han jade cong ritual vessel and the steamed chestnut-coloured Han jade repurposed into four archers’ rings. Use them as the materials for the jade archers’ rings. Follow the design of the new stag antler archer’s ring for its inner rim; follow the design of the old stag antler archer’s ring for the outer rim; follow that of the old archer’s ring for the lower opening; follow that of the new archer’s ring for the upper opening. With regard to the exterior decoration, have one modelled after the pattern on the Han jade beaker vase with archaic motif; have another one modelled after the pattern of the Han jade vase with recumbent silkworm and key-fret patterns; have yet another one modelled after the pattern of the Han jade hand warmer with double-elephant motif; have the other one modelled after the style of the Han jade hand warmer, but decorate it with a hero motif. Have Yao Renzong take care of the Han jade vase. Respect this.5

Comparing these two archival entries, it is apparent that they were describing the same group of objects. Despite the second entry mentioning only one stag antler archer’s ring, its production specifications, cited later in the record, clearly indicate that there were actually two stag antler archers’ rings, one old and one new, corresponding to the first archival entry. Based on the imperial order, two jade objects in this lot, namely a cong ritual vessel and a vase, were reworked into four archers’ rings. Their designs comprised two parts: the inner and outer rims of the top and the bottom of the rings were fashioned after the two stag antler archers’ rings, while their respective embellishments on the body took inspiration from the motifs found on other jades. In the archive records reviewed by the author, these are the first two entries in which the manufacture of jade archers’ rings is mentioned.

It can thus be seen that the origin of the emperor’s commission to make jade archers’ rings, as well as the style of the rings, was not only closely related to the two stag antler examples, but also attributable to the emperor’s personal adoration and promotion of jade. These two stag antler samples served as the prototypes for the majority of jade archers’ rings subsequently made for imperial use.

Production

From the time of the initial manufacture of four jade archers’ rings in May 1751, the Qianlong emperor began to issue continuous instructions for more. On June 8th the same year, an edict ordered the manufacture of six archers’ rings from a white jade stone bearing the image of Tao Yuanming, the poet, entertaining himself with geese, and another archer’s ring made using the leftover material returned to the court.6 On August 5th, an archival entry noted that one piece of rectangular Han jade was submitted. An imperial edict then ordered that it be made into three plain archers’ rings.7 The same day, another imperial edict was issued to have two plain archers’ rings made from the excess material from a Han white jade stone, still being carved, with the motif of a propitious omen.8 In early October, an edict instructed that the lower half of a cylindrical seal be made into an archer’s ring, but to keep the upper half for the seal; another edict ordered that an elongated bead be converted into two archers’ rings; yet another decree demanded that a chi tiger bead be repurposed into one archer’s ring; then one more imperial instruction ordered that a halcyon carriage clock shaped ornament be refashioned into two archers’ rings. On November 3rd: “one piece of black and white Han jade was submitted. Imperial edict: Have archers’ rings made. [The material] should be sufficient for two. Respect this.” On December 7th: “an octagonal Han jade sword handle was submitted. Delivery of imperial edict: Have two archers’ rings made. Respect this.”9 The commands soon came to fruition. On August 13th: “On imperial edict: Ask the Wish-Fulfilling Studio about the making of the two white jade archers’ rings. Since the work report had already been made, what is the reason for not presenting them for inspection?”10

The finished rings were eventually presented to Qianlong for inspection. Because he did not find all of the rings satisfactory, some had to be reworked in accordance with additional requirements. These records paint a general picture of the rings during the first year of their production. It can be gathered that, because of a limited supply of jade, archers’ rings at the time were basically repurposed from existing objects in the imperial collection, and Han jades with colour inclusions were often preferred.

The Bureau of Suzhou Textiles, far away on the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, also soon after began the production of imperial jade archers’ rings. On November 17th, 1751, Eunuch Hu Shijie submitted a piece of white jade bearing the designs of four archers’ rings, four prototypes of the rings, along with two stag antler archers’ rings. Then an imperial edict ordered that they be handed over to the Bureau of Suzhou Textiles to have the drawings taken south to be copied.11 On October 4th, 1752, one southern green jade archer’s ring was submitted, and an edict was issued to have a prototype submitted for imperial viewing. A draft design was submitted to the emperor that day. An imperial edict followed, commanding An Ning of the Bureau of Suzhou Textiles to undertake production in accordance with the design.12 Although the Bureau of Suzhou Textiles undertook the manufacture of archers’ rings, the number of rings produced was far lower than that of the Wish-Fulfilling Studio.

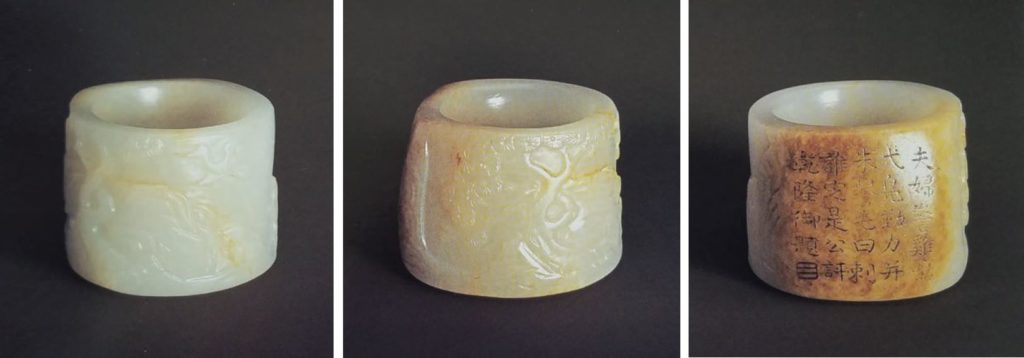

By examining the production archives spanning several decades, it can be deduced that the jade archer’s ring became a regular production item for the Palace Workshops, where several hundred were made. Also, judging from extant examples, the Palace Museum in Beijing has more than 200 such rings, which followed set designs. The bespoke ring made for the Qianlong emperor included the size of the hole, the thickness of the wall, the physical shape, etc. Its original prototype likely came from the two stag antler archers’ rings used by Qianlong himself in his youth, hence the special instructions, as previously mentioned, to “follow the design of the new stag antler archer’s ring for its inner rim; follow the design of the old stag antler archer’s ring for the outer rim; follow that of the old archer’s ring for the lower opening; follow that of the new archer’s ring for the upper opening”. These requirements stipulated the sizes of the inner and outer diameters in the upper and lower sections of the rings. Judging from horn archers’ rings in the Palace Museum collection (6, 7) and the images of those worn by the Kangxi (1662–1722) and Qianlong emperors in their portraits, the ones actually used for mounted archery were usually of a vertical cylindrical shape of identical diameter. As the design of the first imperial jade archer’s ring combined the different sizes of two horn archers’ rings, the style with a wider bottom end and a tapering upper end was thus created. This design was adopted for most of the imperial jade archers’ rings subsequently made for Qianlong. It became the prescribed style for his archers’ rings and is the so-called “His Majesty’s archers’ rings style” mentioned in the archives. This design is also consistent with the majority of the Qianlong imperial jade archers’ rings that still exist today (8, 9, 10).

The Qianlong emperor was also intimately involved in the production of the rings. He raised questions and offered his opinion at each step of the production process for the craftsmen of the Wish-Fulfilling Studio and Bureau of Su-zhou Textiles to follow. As an example, one archive entry recorded:

Eunuch Hu Shijie submitted: one Han jade openwork furnishing item. Delivery of imperial edict: Have Yao Zongren inspect this item to verify its quality and judge whether it would retain its patina if made into an archer’s ring. Respect this.13

This is an example of the Qianlong emperor issuing a direct production instruction and designating a specific craftsman for the task. Other examples follow of the emperor giving specific manufacturing instructions to the craftsmen:

A polished white and russet jade archer’s ring with the pattern of a herd of deer in a maple grove was handed over to Eunuch E Leli to be presented to the emperor. On imperial edict: Production by following the sample is approved. The body and antlers of the deer, the tree and its branches and leaves, the ground and the grass should be carved in relief with red inclusions, while the background should remain white jade. Respect this.14

The figures and houses on the “Autumn Sounds Rhapsody” archer’s ring should be carved clearly. The door on the “Cock Crowing and Dawn” archer’s ring should be black, but the figure inside the door should be white.15

The “Deer” archer’s ring (11, 12) and the “Autumn Sounds Rhapsody” archer’s ring (13, 14), mentioned in the above two archival entries, are currently in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. Judging from these two objects, the emperor’s instructions were followed closely.

From 1751 to January 1799 (the fourth year of the Jiaqing reign), the manufacture of the Qianlong imperial jade archers’ rings continued without interruption. Not only was the emperor closely involved in the manufacturing process, but he also had input into themes and content, which closely followed his personal experience and ideology. Bearing the inscriptions, Qianlong Nianzhi (Made during the Qianlong reign), Qianlong Yuyong (For Qianlong’s imperial use) or the emperor’s own poems, the rings are considered to bear the hallmark of the Qianlong emperor himself.

Qianlong’s poems frequently mentioned memorable experiences from his youth, when he “learned archery in days gone by and was able to hit the target with every shot. Not only did he hit the bullseye, hitting the target repeatedly was an effortless act.”16 From time to time, he would express sadness about being unable to practise archery because he injured his arm when he was fifty. Yet, he often reiterated that the mounted archery event during the annual hunts at the Mulan hunting ground was to be held as usual. His actions demonstrate his determination to defend and promote the Manchu traditions of horsemanship and archery. Numerous hunting themes, including the hunting of tigers, deer (15, 16, 17) and rabbits, appear on the imperial jade archers’ rings, proving the close connection between the ring designs and the emperor’s personal experiences.

The same means of expression also applied to numerous other important occasions in Emperor Qianlong’s life. For example, around 1786 (the fifty-first year of his reign), the emperor had an archer’s ring made with an inscription of his poem, titled Xintian Zhuren Zizhen (Self Admonition for the Ruler who Believes in Heaven), that summarised his early years (18). Then he had a jade archer’s ring made with the engraving, Guxi Tianzi (The Son of Heaven who Turns Seventy), when he reached seventy years of age (19). Yet another example of jade archers’ rings was inscribed Ba Zheng Mao Nian (Concern over Phenomena at Eighty) to mark the emperor’s eightieth birthday (20, 21). All of these rings were made with an identical concept and production method.

Finally, one design was repeatedly replicated. Existing examples indicate that the phenomenon of using one pattern multiple times was highly common, as several archers’ rings bear the same mark or imperial poem. For instance, there are three archers’ rings with the theme of Gong Shi Yu Zheng (bow and arrow metaphor reminding us of our political ignorance), which evidently came from the same drawing in the respective collections of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and the Palace Museum, Beijing (22–27); there are also three archers’ rings inscribed with the imperial poem titled Yong Yu She (Ode to a Jade Archer’s Ring),17 dated 1754 (the nineteenth year of the Qianlong reign) (28, 29), another three with the same poem, dated 1757 (the twenty-second year)18, and yet three more dated 1759 (the twenty-fourth year)19 (30). Archers’ rings, that come in pairs with identical imperial poems, are also commonplace. It is precisely by repeatedly having his imperial poems inscribed on the various jade archers’ rings that the Qianlong emperor was able to impart his own experience and thoughts onto these small-scale objects, and to reinforce this aim through continuous production.

Diameter 3 cm, height 2.5 cm,

Palace Museum Collection, Beijing

The Collection

Differing from archers’ rings made of ivory, horn or wood, the Qianlong imperial jade archers’ rings were not practical objects, serving no function beyond being ornamental. Not visible in Qing imperial imagery, the question arises as to where these rings were kept. A large number were kept in boxes around the palace; according to Palace Workshop archives, the rings were kept exclusively for the emperor’s personal use, connoisseurship and appreciation. Therefore, the majority of the jade archers’ rings produced were incorporated into the magnificent Qianlong imperial collections.

On July 1st, 1752, more than a year after Qianlong had his first jade archers’ ring made, the Box Making Atelier at the Palace Workshops received the following items:

Vice Director Bai Shixiu reported that Eunuch Hu Shijie delivered the following objects: one Han jade four-footed gong libation vessel, wood tray; one white jade four-footed gong libation vessel; one rectangular box made of zitan wood containing ten archers’ rings: one made of tourmaline, four of Han jade, two of white jade; one of agate, one of steamed chestnut-coloured jade, and one made from stag antler. Delivery of imperial edict: Use nine of the archers’ rings contained within the zitan box. Make a box to store the rings by following the style of the four-footed gong libation vessel with a cover hinged at the rear. The box should contain three tiers, with a drawer for each tier. Install pegs. These should be counted as the first work item; then make a rectangular box with a cover. Carve lotus patterns on the base with the engraving of characters in relief. Two dragons should be carved on either side of the walls of the box in the style of those found on the back of the arms of my throne in the Fa Bi Cong (Palace of the Fragrant Grove). Each of the ends should also bear carvings of a dragon with iridescent filigree. Partition the box into ten spaces and also install pegs. This would be counted as the second work item. Samples of both items should first be submitted for imperial review; the third work item would be to remove the silk lining of the rectangular case and polish the interior properly before installing pegs. Each peg should be engraved numerically according to the ten Celestial Stems: jia, yi, bing, ding, wu, ji, geng, xin, ren, gui. Store the ten archers’ rings with chiming clocks within. Respect this.20

Reminding Us of Our Political Ignorance” Archer’s Ring, Diameter 3.1 cm, height 2.5 cm, Palace Museum Collection, Beijing

Metaphor Reminding Us of Our Political Ignorance”

Archer’s Ring

According to the work specifications, the Box Making Atelier was to make one zitan three-tiered archers’ ring box with a cover emulating the style of the four-footed gong libation vessel. Then it should make a single-layer zitan rectangular lidded box with dragons carved on the four sides, imitating the dragon design found on the throne in the Palace of the Fragrant Grove within the Yuanming Yuan. Meanwhile the atelier was also instructed to polish the interior of the rectangular zitan box, install pegs and then engrave numbers on them for future usage. This is the earliest record found during the Qianlong reign mentioning the storing of jade archers’ rings in boxes.

The production process and the pairing of archers’ rings with boxes were recorded in detail in the Palace Workshop archives. The Box Making Atelier soon designed a zitan archers’ rings box with two shelves, following the style of the four-footed gong libation vessel. After obtaining approval for production, the box was completed on September 24th the same year, and was handed over to Eunuch Hu Shijie to be presented to the Qianlong emperor.21 On the same day, the emperor issued a decree to have the box turned over to the Wish-Fulfilling Studio for filigree embellishments to be added. Therefore, the Wish-Fulfilling Studio submitted a design with a kui dragon motif against a scrolling-cloud background framed by key-fret bands. Qianlong then instructed that gold filigree be added to the key-fret, silver filigree added to the kui dragons, and gold leaf added to the background, with a completion deadline of October 3rd, 1753.22 One year later, the box, along with selected archers’ rings, was handed over to the Box Making Atelier once again.

Eunuch Wang Bing reported that, on the twenty-fifth [of this month], Eunuch Hu Shijie handed over: one zitan lidded box with gold and silver filigree inlay containing three white jade archers’ rings, two Han jade archers’ rings with nicks, and one steamed chestnut coloured jade archer’s ring. Delivery of imperial edict: Make a brocade box with brocade cushioning for the rings. Assign it to the top grade when it is to be stored in the Qianqing Gong (Palace of Heavenly Purity). Respect this.23

By the time the first zitan archers’ rings box was finally placed in the Palace of Heavenly Purity, the entire process had taken more than two years. The lidded box, which later became the style for subsequent archers’ rings boxes, became commonly known as a trefoil box (31). Its external shape displays the contour of three interconnected circles, while the interior ingeniously provides the perfect amount of separate circular spaces to accommodate the cylindrical rings. Archival records indicate that this design concept was also applied to dual-leaved boxes (32)24 and quatrefoil boxes in the four-footed gong libation vessel style (33). Examples of such boxes can be found in the Qing court collection as well.

During the Qianlong period, numerous archers’ rings were stored in lacquer boxes. The smooth interior of these boxes could not hold the rings in place, so bespoke wooden liners had to be made. These are the so-called archers’ rings trays, mentioned in the archival records, to keep the rings separate, but secure. Lacquer boxes with wooden trays were regularly produced during this time. Usually, they were made by the Suzhou Textile Bureau, while tray-related woodwork was undertaken by the Palace Workshops. For instance, on October 16th, 1755:

Vice Director Lang Jinhui and Vice Supervisor-General Shu Wen reported that Eunuch Hu Shijie submitted: one carved cinnabar lacquer powder box with three zitan archers’ rings trays, one carved cinnabar lacquer circular box with two zitan archers’ rings trays. Delivery of imperial edict: send the two lacquer boxes to Suzhou and have identical ones made. Have the trays for these boxes made in the capital by following the samples provided.25

From these archival records, it appears that the imperial jade archers’ rings produced during the Qianlong reign were stored by group in bespoke boxes. Some of these boxes were made of zitan wood, while others were made of carved cinnabar. The number of archers’ rings contained in these boxes varied, from one or two to as many as twenty-five. The interior designs of the boxes were all made for specific purposes. Each was equipped with wood liners, tray dividers, pegs, cushioning and silk liners to separate and secure the rings. Some of the boxes bear inscriptions of Emperor Qianlong’s poetry, eulogising jade archers’ rings, on their exterior, interior and tray dividers, making them all the more exquisite and meaningful. A set of seven Qianlong imperial jade archers’ rings, auctioned by Sotheby’s Hong Kong in 2007, afforded a glimpse of a typical set (34).

Most of the rings were stored in palaces or gardens, such as the Forbidden City, the Garden of Perfect Brightness, or the Summer Resort at Rehe (Chengde). Within the Forbidden City, the primary location for storing the rings was the Palace of Heavenly Purity. For example:

For the pair of carved cinnabar lobed boxes containing sixteen archers’ rings, the imperial edict commands that they are to be fitted in a brocade box and a cloth wrapper before entering storage as top grade in the Palace of Heavenly Purity. Respect this.26

Another storage location was the Jiuzhou Qingyan (Hall of Peace in Nine Lands) within the Palace of Perfect Bright-ness. For example:

The placement of the seven inscribed jade archers’ rings, that were delivered from Suzhou and had already been presented, was completed.27

The Yanbo Zhishuang Dian (Hall of Refreshing Mists and Waves), located in the Summer Resort at Rehe, was another repository. For instance:

[Regarding] the carved cinnabar circular box with ten archers’ rings kept within the Hall of Refreshing Mists and Waves, the imperial edict commands it to be matched with a shaobing flatbread-shaped zitan stand of the height of five fen. Respect this.28

As these were the palaces most frequently visited by Qianlong where sizable collections were kept, it is hardly surprising for collections of imperial jade archers’ rings to have been found.

The emperor’s constant adjustments to, and focus on, his ring collection can be observed in archival records in terms of the manufacture and quantity of jade archers’ rings and their boxes, as well as their storage locations. The collection of archers’ rings, along with other court collections to which the emperor devoted his attention, paint a vivid picture of court collecting and connoisseurship in the Qianlong period.

The Award of Imperial Jade Archers’ Rings

It is clear that the production of jade archers’ rings took place due to Emperor Qianlong’s promotion and attention, reflecting his personal taste and aesthetic proclivity. However, if the production, collection and appreciation of these rings were limited merely to the emperor and his court, the rings might not have received much attention. In fact, they were gradually disseminated outside the palace, being awarded to worthy officials, so that they became accoutrements for military personnel.

The earliest known award of a jade archer’s ring occurred in 1757. In order to quell the Dzungar Khanate and Muslim rebellions, General Zhao Hui, who was stationed in Yili, Xinjiang, led the Qing army through numerous battles facing overwhelming odds before eventually bringing the northern and southern regions of the Tianshan Mountains under the control of the Qing administration. Upon his triumphant return to Beijing, the Qianlong emperor personally led Zhao Hui’s horse into the city and presented an imperial jade archer’s ring to him; this was deemed at the time to be one of the highest honours. The jade archer’s ring thus entered the list of official awards, while this incident also served as a precedent for worthy Qing generals to be rewarded accordingly.

Subsequently, the continued fortification of the frontier and stabilisation of Qing rule led to an increasing number of jade archers’ rings being awarded throughout the remainder of the Qianlong reign. Based on award records, the following information can be inferred:

First, the award of jade archers’ rings was focused: with a few exceptions, the recipients were army generals who achieved outstanding military success. They had either made an extraordinary contribution in strengthening or defending the Qing empire or in maintaining order and social stability. These military commanders, who served as a critical stabilising force during the Qianlong reign, thus received special attention and commendation from the emperor himself. For this reason, the jade archer’s rings came to symbolise military achievement.

Second, the award of jade archers’ rings was based on a hierarchical system. A comparison of all the award records makes apparent that Qianlong used notably different expressions when conferring jade archers’ rings, forming a five-grade award system, comprising: the Han jade archer’s ring I personally removed from my hand today; jade archers’ rings that I wear; jade archers’ rings for imperial use; jade archers’ rings; and the four-happiness archers’ rings. An example of the Qianlong emperor awarding ‘the Han jade archer’s ring I personally removed from my hand today’ occurred in February 1788 when General Fu Kangan reported that the army he led to quell the Lin Shuangwen rebellion in Taiwan had achieved final victory. “[I] awarded Fu Kangan the Han jade archer’s ring I personally removed from my hand today along with a small pouch”.29

As for the “four-happiness archers’ rings”, these were awarded collectively and simultaneously to worthy generals. One occasion, when multiple ‘four-happiness archers’ rings’ were awarded, was after a battle against the Gurkhas in 1792. Different materials were used for the archers’ rings, apparently including: Han jade rings; white jade; and spinach-green jade. The colour of the ring signified its importance. Han rings with coloured inclusions were those most favoured by Qianlong, most of which were for imperial use or imperial collection.

Third, the number of jade archers’ rings awarded was inextricably associated with a military commander’s accomplishments. According to records, the Qianlong emperor awarded a total of seventy-four jade archers’ rings, with Fu Kangan receiving the most, a total of nine. He Lin ranked second, with seven rings, while Hai Lancha came next, with four rings. They were all eminent military commanders, who had fought numerous battles and were considered indispensable aides to the emperor. Status, relationship and grade all manifested themselves in the award of an archer’s ring, whether in the number of awards received, the level of the award, the material from which the ring was made or whether it was given in combination with another item. The award of these rings seems to have become an indication of a general’s individual military feats and the bond between the emperor and the officials who provided meritorious service. The more jade archers’ rings bestowed upon an individual, the greater his martial accomplishments. The higher the grade of award, the greater the recognition received.

Small Symbol of a Golden Age

Although the archives of the Palace Workshops and the actual objects themselves serve as good resources to examine and understand jade archers’ rings, Emperor Qianlong’s own poems should not be overlooked. From 1752 to 1797 (the second year of the Jiaqing reign), he composed more than fifty poems on this subject, providing indications as to the reasons for his promotion of the production and collection of these rings and his decision to use them as rewards to honour military leaders for extraordinary service. On the one hand, advocating the manufacture and collection of jade archers’ rings derived from the need to preserve traditional Manchu culture, since mounted archery had long been regarded as the foundation of the Qing empire. Qianlong once said:

As mounted archery is the ruling discipline of my dynasty, [I] often instruct my offspring that this tradition should be observed for eternity. Therefore, even though I am over seventy years of age, I always visit Mulan annually to hunt there. I am still able to maintain my control with ease and can often end my hunts with kills, for I lead by action and dare not allow self-indolence.30

As an indispensable accessory for mounted archery, the rings reminded people of the importance of the skills involved. This point was often emphasised by the emperor in his poems on archers’ rings. Some examples include:

[Archers’ rings] help conquer the foreign Barbarians. Their significance will always be remembered;

[It is in my people’s] long-standing family law to pass down the skill of archery. The archers’ rings handed down by my predecessors are kept until this day;

Can one truly forget about disciplining the army that is everywhere that meets the eye;

Even the virtuous jade can still be subject to different interpretations. How dare one feel instant happiness from military accomplishments;

Most Confucian scholars tend to de-emphasise the importance of military affairs, and prosperous dynasties tend to value literature. Dare I slacken because family law has been loosened? I still practise diligently by myself on the hunting ground; and

An ingenious craftsman presented a new style of archer’s ring engraved with a mounted hunting scene. I commend it for implying the importance of military training, which is different from that which focuses only on the pursuit of pleasure.

Through the small archer’s ring, the emperor wished to express his sense of urgency in striving to safeguard his family history and the ruling precepts of his court.

On the other hand, the focus on jade, and the reflection of human characteristics through the appreciation of objects, are highly consistent with Emperor Qianlong’s thinking on jade ware. Because the making of jade archers’ rings set extraordinary standards in the quality of materials used, the emperor often employed such expressions as “gorgeous”, “exquisite”, “stunning”, “rare treasure” to describe the fine material utilised. He not only viewed these rare, exquisite and lustrous jades as treasures for appreciation, but was also influenced by a traditional Chinese concept, that “a gentleman compares his virtue to a jade”, and subconsciously sublimated his appreciation for the beauty of jade to a focus on the cultivation of virtue in life.

Examples of this philosophy can be found in the emperor’s poems, some of which read:

I often view objets d’art and try not to put them down, for I truly feel that such virtuous materials delight the spirit;

Square one’s body and calm one’s mind so that one can unravel things with deeper meanings. The combination of ancient classics and chronicles instruct us to commit no evil;

Often, I would ponder and observe virtue, evoked by the ring’s pristine lustre. Not only do I explore

enlightenment, but also marvel at its unsurpassed beauty; and

The desirable virtue of this ring inspires respect, while its integrity is worthy of study.

This way of reflecting on mankind through the appreciation of objects undoubtedly greatly enriched the humanistic quality contained in the jade archers’ rings, while also affording us a glimpse into the inner world of the Qianlong emperor.

Moreover, jade archers’ rings are highly expressive. They are tangible forms and important exemplars of the art of jade carving. Although they are small, their production was far from simple, especially those with intricate patterns or inscribed imperial poetry. Combining images of people, animals and natural landscapes with text, to form refreshingly natural scroll-style paintings or thought-provoking calligraphy in such a tiny space was certainly no easy feat for the designers, let alone for the carvers. Such achievements could not have been possible without extraordinary craftsmen, ensuring that the rings were worthy of refined connoisseurship. It is no wonder that the Qianlong emperor repeatedly praised them in his poetry.

Most importantly, the archers’ rings were also a form of jade ware that represented the Qianlong emperor’s construct of a Golden Age, embodying his glorious achievements and political thought. Qianlong had meticulous plans to create a glorious era in Chinese history, and amassing (and refining) his court collections was but one of the essential components of his vision. Through systematic accumulation, Qianlong created a connection between his own life and the formation of a prosperous era. To achieve this end, he cleverly embedded his personal experiences in the collections by making them vessels of his marvellous feats. This trait was also manifest in the endorsement of the production and collection of imperial jade archers’ rings, thus enabling them to become a new category in the court collections and a vehicle for his political thought and his military achievements.

Conclusion

It was precisely because of Emperor Qianlong’s passion for jade and his aim to safeguard the Manchu tradition of mounted archery that he decided to have archers’ rings made of jade instead of ivory or horn. The decision prompted these rings to evolve from being practical archery accessories into fashionable ornaments. The varied colour of jade and the expressive nature of the rings enabled them to become jade ware representing the emperor’s construct of a Golden Age. Archers’ rings consequently had an enduring artistic quality, cultural connotation and historical value that qualified them to enter the palace collections.

As a novel category of jade ware, that came into existence at the pinnacle of jade production during the Qing dynasty, the archers’ rings were closely connected to the Qianlong emperor and his reign. Although jade archers’ rings have been discovered in preceding dynasties, they did not become collectibles or objects for appreciation until the Qianlong period.

The rings were first manufactured in May 1751 when Qianlong ordered craftsmen in the Palace Workshops to design and produce jade archers’ rings emulating two stag antler archers’ rings that he had been using for more than thirty years. Over the next fifty years, until his death, several hundred of these rings were produced. As a novel and popular genre, the production, collection and award of jade archers’ rings were closely associated with the ambitious goals that the Qianlong emperor had set in creating jades epitomising a flourishing society. Last, but not least, the jade archers’ rings also served as examples for the study of historical jade forms during the Qianlong period.

1 [Eastern Han] Xu Shen, Shuo Wen Jie Zi (An Explication of Written Characters), Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1983, p.111.

2 Misc (Confucian School), The Shi King, the Old “Poetry Classic” of the Chinese: A Close Metrical Translation, with Annotations by William Jennings, London: George Routledge and Sons, 1891 (accessible at https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2109).

3 [Qing] Hongli, “Yong Yu She”, Yu Zhi Shi Er Ji, scroll 32.

4 “Ji Shi Lu”, May 1751 (the sixteenth year of the Qianlong reign), Qing Gong Nei Wu Fu Zao Ban Chu Dang An Zong Hui, edited by the First Historical Archives of China and the Art Museum the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Beijing: People’s Publishing House, Vol. 18, 2005, p. 377. All entries from this book are referred to below as Zong Hui.

5 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, June 1751, pp. 346–347.

6 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, August 1751, p. 354.

7 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, August 1751, p. 352.

8 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, August 1751, p. 353.

9 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, March 1752 (the seventeenth year of the Qianlong reign), p. 596.

10 “Ji Shi Lu”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, August 1751, p. 393.

11 “Suzhou”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, November 1751, p. 415.

12 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, October 1752, p. 604.

13 “Ji Shi Lu”, Zong Hui, Vol. 18, November 1752, p. 708.

14 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 41, June 1778 (the forty-third year of the Qianlong reign), p. 797.

15 “Xing Wen”, Zong Hui, Vol. 45, January 1782 (the forty-seventh year of the Qianlong reign), p.391.

16 [Qing] Yu Tao Hua She”, Yu Zhi Shi Si Ji, scroll 14.

17 [Qing] Hongli, “Yong Yu She”, Yu Zhi Shi Er Ji, scroll 48, First sentence: Jia Zai Yan Xi Zhi.

18 [Qing] Hongli, “Yong Yu She”, Yu Zhi Shi Er Ji, scroll 73, First sentence: He Nian Yu Hua Zhou

19 [Qing] Hongli, “Yong Yu She”, Yu Zhi Shi Er Ji, scroll 88, First sentence: Lian Zhen Zhi Zi Gu.

20 “Xia Zuo”, Zong Hui, Vol. 19, July 1752, pp. 65–66.

21 “Xia Zuo”, Zong Hui, Vol. 19, July 1752, p. 66.

22 “Ruyi Guan”, Zong Hui, Vol. 19, October 1753 (the eighteenth year of the Qianlong reign), p. 563.

23 “Xia Zuo”, Zong Hui, Vol. 20, December 1754 (the nineteenth year of the Qianlong reign), p. 147.

24 “Mu Zuo”, Zong Hui, Vol. 23, June 1757 (the twenty-second year of the Qianlong reign), p. 25.

25 “Ji Shi Lu”, Zong Hui, Vol. 21, October 1755 (the twentieth year of the Qianlong reign), p. 493.

26 “Xia Biao Zuo”, Zong Hui, Vol. 52, December 1790 (the fifty-fifth year the Qianlong reign), p. 318.

27 “Xing Wen”, Zong Hui, Vol. 48, October 1785 (the fiftieth year of the Qianlong reign), p. 269.

28 “Re He Sui Wei”, Zong Hui, Vol. 36, May 1773 (the thirty-eighth year of the Qianlong reign), p. 165.

29 Qing Gao Zong Shi Lu, scroll 1299, February 27th, 1788 (the fifty-third year of the Qianlong reign).

30 [Qing] Hongli, annotation of “Yong He Tian Yu She”, Yu Zhi Shi Wu Ji, scroll 33.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift