PETER Y.K. LAM

IN 1662, XUANYE (1654–1722) ascended the throne as the Kangxi emperor. His 61-year reign (1661–1722) was the longest in the history of dynastic China (1). The ceramic output from the Imperial Porcelain Factory in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, during this period not only set standards for later reigns to follow, but also brought new forms and innovative technical virtuosity to the pottery manufacturing process. This article attempts to plot the development of Kangxi imperial porcelain, against the respective tenures of the imperially appointed supervisors and designers of porcelain production at Jingdezhen, by making reference to examples in the Dawentang Collection, assembled by Lawrence and Hedy Chan in Hong Kong.

According to recent studies, after the Qing conquest of the Ming regime in 1644, neither the staffing nor the management of the Imperial Porcelain Factory in Jingdezhen underwent any drastic change.1 Production activities continued as usual. The existence of a few high-quality ceramic pieces bearing six-character Shunzhi (1644–1661) reign marks in museum collections is evidence of the early imperial wares of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Documentary records show that the Department of Works transmitted edicts to Jingdezhen to produce massive dragon bowls and porcelain architectural panels from 1654 to 1660.2 However, after several failed attempts, production was not pursued further. Then, in 1671, the young Kangxi emperor commissioned the production of sacrificial vessels and other ritual pieces, probably for the mausoleum of his father. However, production did not start until as long as three years later, in 1674, as rebel armies from the Three Feudatories attacked Jiangxi province. Jingdezhen was sacked, kilns and workshops were burnt and destroyed. It was not until another three years later that the town was pacified and ceramic production resumed; and only then were commissions on a grand scale accepted from the Imperial Household Department in Beijing.

In the nineteenth year of the Kangxi reign (1680), four supervisors were appointed, and they arrived at Jingdezhen the following year (1681) to oversee production. The team consisted of Xu Tingbo, Director, Li Yanxi, Secretary of the Storage Office of the Imperial Household Department, Zang Yingxuan, Director, and Che Erde, a clerk in the Bureau of Forestry and Crafts, Ministry of Works (2). The production of this order continued until 1688, when it was terminated for reasons unknown.

Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

The designer of the ceramic forms and patterns of this massive imperial order was Liu Yuan (circa 1641–circa 1691), a Chinese bannerman from Xiangfu, Henan province (3). His bibliographical details are very sketchy, but he was a versatile and talented artist. Apart from being an accomplished painter and calligrapher, he was a carver of inkstones and wood, a designer of imperial porcelain wares, imperial seals, inkcakes and lacquerware. Liu initially worked in Suzhou, but soon enrolled as a student at the National University in Beijing. Later, he took up a Secretarial position at the Ministry of Justice and was posted to Guangxi province. He was then transferred to the post of Tax Commissioner at the Wuhu Customs Office, Anhui province, but was dismissed from his post in 1679 after being accused of misconduct. He was called back to Beijing to serve at the Inner Court, but passed away sometime thereafter.

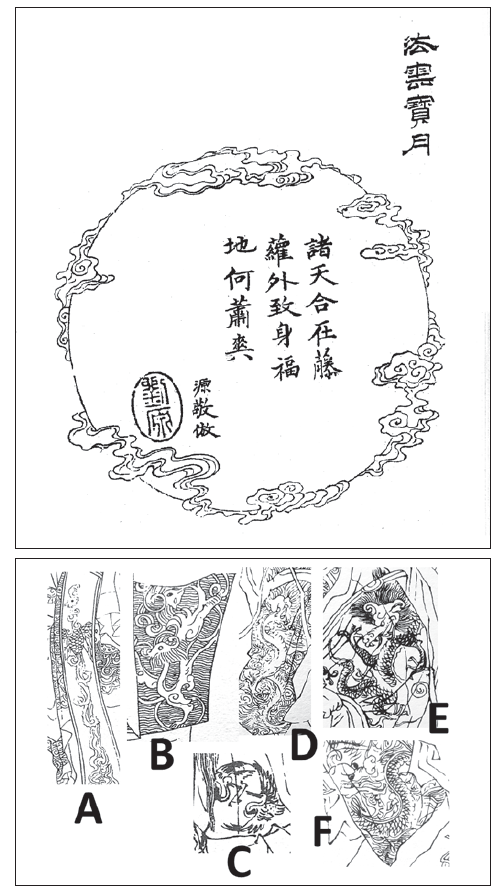

Liu’s biography in the Qingshigao, the official history of the Qing dynasty, includes a very important remark related to his ceramic designs: “At that time, the Imperial Porcelain Factory in Jingdezhen was about to produce imperial pieces. Liu presented several hundred porcelain designs, making reference to examples found in ancient and modern times, while injecting his own innovative ideas … when completed, the output surpassed the wares of the former Ming dynasty.” If we try to fit this description into Liu’s chronology, the only possible time for him to have contributed these ceramic designs would be after his return to Beijing, i.e. after 1679. This also coincided with the imperial order, given in 1680, to send four supervisors to Jingdezhen for the large-scale order that would last until 1688. Taking into consideration Liu’s personal style in other artistic endeavours, such as painting, woodblock illustration (4) and designs found in other media signed by him, there is now a consensus that all of the forms and the decorative repertoire found on Zang wares were designed by Liu Yuan (5).

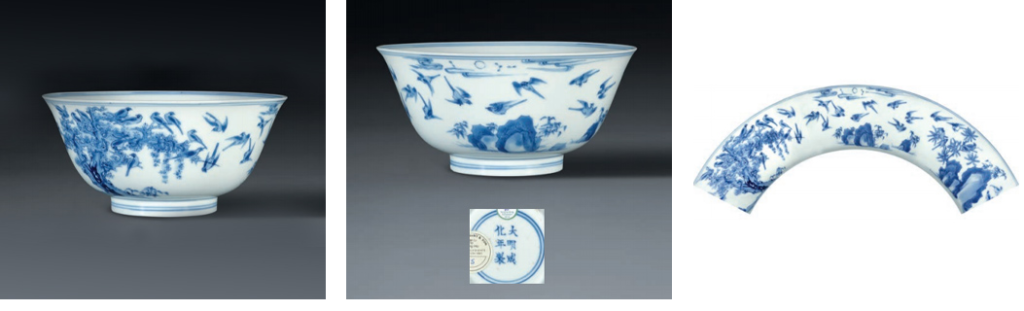

Most important is the re-attribution of the peachbloom glaze and related items in sky blue, celadon and white glazes to the time of Liu Yuan (i.e. from the early to mid-Kangxi period). Previously, most scholars dated these to the last decade of the lengthy Kangxi reign. There are other clues as to the identification of porcelain wares designed by Liu. Recently, scholars have focused on the classification of different styles of reign marks appearing on Kangxi imperial wares. Most of these marks are in standard script, unlike those from later reigns, and are seldom found in seal script. The marks of the early to mid-Kangxi reign have telltale features: a slender calligraphic style, very different from the more standard mark in the so-called Songti script of later decades (6-E&F). Liu’s design set an elegant standard for imperial porcelain of the subsequent Yongzheng (1723–1735) and Qianlong (1735–1796) reigns.

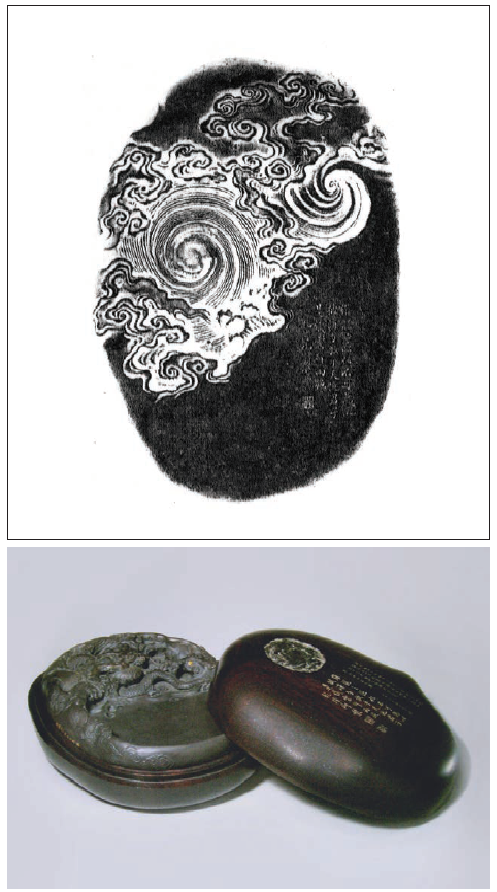

The “horse-hoof” water-pot, with steep domed sides rising to an in-turned mouth with a slightly lipped rim, is a hallmark shape designed by Liu Yuan (7). Under the transparent glaze, the pot is elegantly carved on either side with cascades of billowing clouds; their subtle relief gives the design great depth and movement. This water-pot is among a distinctive group of monochrome objects designed by Liu, whose colour spectrum includes white-glazed, lavender-blue, claire-de-lune, sky-blue, celadons of various tones and peachbloom wares, coming in a number of forms, such as moon-shaped vases with handles, shuanglu chess-shaped bottles, chrysanthemum-petal vases, willow-leaf vases, pomegranate-shaped pots, horseshoe bottle vases, horse-hoof water-pots, tulip vases, sun-moon vases, apple-shaped water-pots and petal-shaped small dishes. Liu’s ceramic decorative patterns can often be traced to the borders of his woodblock prints (see 4-A), in particular, his silky and wavy cloud patterns, as seen on this pot.

The beehive-shaped water-pot, with a small short neck and slightly everted mouth rim, a hemispherical body and a slightly sunken flat base, is another form designed by Liu Yuan (8). There are three incised roundels of stylised chi-phoenixes on the exterior. The shade of the soft peachbloom glaze, which was blown on, is mottled in crushed strawberry red tone. This form of water-pot first appeared in the Kangxi reign, when it was used on the scholar’s desk to hold water for washing brushes or to hold a single floral display. The peachbloom glaze (or red-bean glaze in Chinese) was a continuation of the copper-red glaze tradition from the Yuan and Ming dynasties. It was first invented in the early Kangxi period and was regarded as a very rare type of exceptional quality. Chemically, the red colour is the result of a very complicated “in-glaze” phenomenon. To achieve this unusual effect, fine grain copper pigment was sprayed onto a clear glaze and then covered with another clear glaze, so the copper was effectively sandwiched between two transparent glazes before the whole piece was put to high firing. Fluctuations in various factors in the firing, such as the atmosphere, the form, the intensity and size of the copper particles, all contribute to the end result. The final colour, though unpredictable, often consists of eye-catching patches of different tones of red, together with some mossy green dots or mottles. The incised phoenix medallion on the exterior, may again be compared to similar decorative borders printed on Liu Yuan’s woodblock illustrations in his Meritorious Figures of the Linyan Pavilion (see 4-B).

Liu also rendered his design skill on blue and white porcelain. The illustrated box cover is delicately painted with a central medallion enclosing a butterfly with outstretched wings, and surrounded by four further butterflies interspersed amongst stylised crab apple flower sprays (9). The sloping sides of the cover are painted with six groups of butterflies and crab apple flower scrolls, repeated on the sides of the box. Flowering crab apple and other floral patterns used in conjunction with butterfly motifs are often seen on embroidery and gold and silver ornaments of the Ming dynasty. At the Dingling mausoleum of the Wanli emperor (reigned 1573–1620), for example, a thin silk skirt, embroidered with a butterfly and crab apple flower pattern in red, was uncovered on the northern side of the coffin of Empress Xiaojing (who passed away before the emperor in 1611) (10). The word for crab apple flower in Chinese puns with the word tang (hall), while the word for butterfly is pronounced die (a homonym for the Chinese word for old age, between seventy and eighty years old). The pattern, as a whole, therefore, connotes “may the entire hall be filled with longevity”. The mark inscribed on the base is in a three-column standard script format, with the calligraphy arrangement and style belonging to the early Kangxi period (6-E&F). At that time, the Kangxi emperor was still young. Of all the imperial consorts and court ladies, the only person with the privilege of using this box was Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang (1613–1688), the emperor’s grandmother (11). If tang (hall) is taken as an abbreviation for gaotang (parents and grandparents), this box is even more appropriate for the grand position and age of the Empress Dowager. As such, this box was most likely potted by Jingdezhen artisans as an exquisite tribute to celebrate the birthday of the Empress Dowager in the 1680s.

Another piece designed by Liu Yuan is the delicately potted cup painted in underglaze copper red with roundels of stylised phoenixes with outstretched wings (12). Each roundel is painted in copper red accented with green speckles. Underglaze red uses copper as a colourant. It is an extremely difficult pigment with which to work and very stringent control of the kiln atmosphere, temperature and intensity of the copper ore content is needed to produce a good bright red colour. If there is any deviation in any of the variables, the copper becomes volatile and the copper red can turn grey or green, or the colour can even disappear altogether. The firing of underglaze red in Jingdezhen first started towards the end of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), and reached its peak during the Yongle (1403–1424) and Xuande (1426–1435) periods of the Ming dynasty. From then on, an underglaze red of a less pure and fine quality was produced. It was not until the Kangxi reign when the potters of Jingdezhen once again revived the prized technique of making underglaze copper red. This period witnessed the successful recreation of underglaze red and sacrificial red, as well as the development of other new copper-red variations, including the famous Langyao red (sang de boeuf), peachbloom red, etc. The dragon medallion and phoenix medallion motifs are typical of Liu Yuan’s creations. The red phoenix is seen stretching its legs downwards towards the left, which is another unusual design by Liu, that cannot be found on any other phoenix roundel made during the mid or late Kangxi period, or in later reigns. All of these minute details demonstrate the elegant and courtly style of Liu Yuan in the design of imperial porcelain.

The green and yellow bowl is engraved and enamelled, with two five-clawed dragons striding towards flaming pearls among flying clouds, together with two phoenixes in flight. The centre of the interior is decorated with a stylised shou (longevity) character encircled by a plain-line band (13). The motifs are all coloured in brilliant emerald-green enamel on a clear translucent yellow ground, with the green enamel running slightly beyond the engraved outlines. Yellow and green wares of the Qing dynasty were exclusively produced by demand from the imperial palace. The exterior of this bowl is finely incised with a dragon and phoenix motif. The most marked feature, unlike those of the following reigns, is that the tails of the two phoenixes on this bowl are depicted in different formats. This follows the Yuan dynasty tradition where phoenix tails are classified into two types: foliated and multifurcated, according to gender. This bowl is evidence of how the early Qing imperial palace inherited Yuan and Ming traditions. The reign mark on this bowl belongs to the second phase of the Kangxi period, i.e. between 1681 and 1688 (6-E&F). This coincides with the tenure of Liu Yuan, whose innovative Zang wares were among new initiatives in contemporary ceramic design during the period. The shou character, inscribed in seal script at the centre of the interior (13), also lends itself to further consideration.

The Kangxi emperor ascended the throne at the age of eight in 1661 and his mother passed away one year later. He was raised by the Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, whom he held in great respect throughout his life. In the period corresponding to the Zang ware discussed above, i.e. 1681–1688, the Kangxi emperor was still a relatively young man and, according to the Veritable Records of the Kangxi Reign, he was never fond of celebrating the wanshou jie (the emperor’s birthday). It is, therefore, logical to postulate that this green and yellow shou character bowl with a dragon and phoenix motif was a tribute gift specifically produced to celebrate the shengshou jie birthday of the Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang. As she passed away in 1688, the timing matches the emergence of the Zang wares designed by Liu Yuan.

Lang Tingji (1663–1715), a native of Guangning, Liaodong (present-day Beizhen, Liaoning province) (14), was another important player during the Kangxi reign. In 1681, at the age of nineteen, Lang Tingji began his official career as a Sub-prefect of Jiangning, Jiangsu province. After being promoted for distinguished service through various offices in Yunnan, Shandong, Fujian and Zhejiang provinces, he was appointed Governor of Jiangxi in the summer of 1705. He was stationed in Nanchang, the provincial capital of Jiangxi, remaining at this post until 1712. In the second month of that year, the 51st year of the Kangxi reign, he was made concurrently Acting Governor General of Jiangsu and Anhui and moved to Jiangning (Nanjing) in Jiangsu province. Seven months later, he was promoted to the position of Director General of Grain Transport, looking after the Grand Canal and the transportation of provisions to the capital. He was relocated to Huai’an in Jiangsu province where he died three years later, in 1715. Lang Tingji’s lengthy term of service as Governor of Jiangxi and nearby provinces, and his personal interest in the local pottery process, have led him to be associated with a special type of copper-red ware (so-called “Lang ware”) of the late 17th and the 18th century. However, as this group of “Lang ware” shows in variations in form, glaze, foot formation and the colour of the patchy glaze on the foot, recent scholarship has suggested that the production period of “Lang ware” might have been extended beyond the brief eight-year tenure of Lang in Jiangxi, so the attribution of this group of sang-de-boeuf ware to Lang would have been a misnomer. Making use of the descriptions recorded in poetry and literary records by contemporaries of Lang, scholars have found that the characteristics of true Langyao ware were faithful copies of Ming classical wares of the Xuande and Chenghua (1465–1487) reigns, consisting of monochromes and blue and whites. Also, the identification of Lang’s private studio mark, “Yuchi Chunyi Tang”, has helped to pinpoint the true features of these Lang wares. Before he left Jiangxi, Lang initiated and carried out the supervision of the tribute porcelain to honour the sixtieth imperial birthday celebration of the Kangxi emperor in 1713.

Two small dishes in the Dawentang Collection might be examples of such birthday tribute ware overseen by Lang (15). Each of the dishes is dainty and so thinly potted that they have an eggshell-like quality and are considered tuotai, or “body-less”. The centre of the interior of each dish is exquisitely painted in the famille-verte palette, with a leafy branch bearing a large green peach with a yellow tip merging into red and green. The branches are outlined in brown pigment. The leaves are painted in lush green, some edged in light brown to pick out the withering borders. The exterior is plain. When held against the light, the images on the interior of these two dishes are almost visible from the exterior. This is likely the reason why a Kangxi reign mark was not inscribed onto the bases. The colouring of the famille-verte pigments on the dishes is well applied. Despite the limited space, fine details of the illustrations have been precisely rendered, and appear sharp and clear. The edges of the two peach leaves taper off in brown pigment to bring out the withering parts. The veins of the leaves are outlined in black enamel and painted over with transparent green glaze to create a glossy effect. The stems are outlined in brown to highlight the profile, with tiny buds at the tips. Pointillist black spots have been added in-between the leaves and the peach on the dish on the right. The black dots on top of the peach, protected by an overlay of transparent green glaze, display a more prominent and vibrant tone while the dots in the gaps between the branches and leaves tend to be of a light greyish hue. This creates a colour contrast and enhances the effect of the colour variations. The peach is a symbol of longevity and is a common decorative motif on ceramic wares produced for the annual celebration of the emperor’s birthday. In this group of extant wucai dishes potted by official kilns during the Kangxi reign, decoration using peaches on branches, like that on the present pair, could often be found. Some of them have peaches inscribed with shou or wanshou characters in seal script in gold or black enamel, indicating that they were potted specifically for the imperial wanshou jie (16). The six-character reign mark in standard script on such dishes is invariably in the same style of calligraphy as the reign mark on wares fired during the tenure (1705–1712) of Lang Tingji—the eight years when Lang served as Provincial Governor of Jiangxi (6-G&H). One might perhaps suggest that these dishes were potted to celebrate the emperor’s sixtieth birthday in 1713.

Based on historical records, during the interim period between the Kangxi and Yongzheng reigns, the people responsible for the Imperial Porcelain Factory at Jingdezhen were members of the An family: An Chi (1683–after 1742) and his father, An Shangyi.3 An Chi was a connoisseur of traditional calligraphy and painting, and his catalogue, Moyuan Leiguan, is an indispensable reference tool for all students, scholars and collectors of classical Chinese painting and calligraphy (17). Originally from Korea and hailing from a famous salt merchant family, An Shangyi was ordered in the latter years of the Kangxi reign to send his family members to Jingdezhen to supervise imperial porcelain production. However, during this period, the old Kangxi emperor was indecisive in the appointment of his heir apparent; the appointment and abolishment of the designated crown prince became a frequent occurrence, and many imperial family members conspired to seize the throne. After his enthronement in 1722, Emperor Yongzheng bore resentment against his brothers and their lackeys, who had attempted to seize power. An Shangyi was the servant of Ming Zhu (1635–1708), whose son, Kui Shu (1674?–1717), was a supporter of two of Yongzheng’s brother-contenders. After ascending the throne, Yongzheng was, thus, suspicious of the An family. In a vermillion rescript, Yongzheng stated that An and his family “refused to submit to authority”, specifying their use of the former Chenghua imperial reign mark instead of the legitimate Yongzheng base mark when firing imperial porcelain in Jingdezhen. The real reason this was done was most likely a continuation of the long custom of imitating the famed Ming ware, which had been practised in the late Ming and in the early Kangxi period. Yet, Emperor Yongzheng regarded it as disrespectful to himself, the newly enthroned emperor. An Shangyi, An Chi and their family were subsequently dismissed from their positions.

The blue and white magpie bowl, with an apocryphal Chenghua mark, is a typical late Kangxi–early Yongzheng piece, coinciding with the short tenure of the An family’s supervision of imperial wares during this transitional period (18). Painted on the exterior of this bowl is a continuous scene of thirty magpies: some are perched upon intertwined vine branches of a large ancient tree; some are in flight above bamboo and rockwork, with clouds, the moon and constellations overhead; and others are hovering over branches of pine issuing from rockwork. The drawings were portrayed in outline first, with further gradated washes added, all in an underglaze blue that resulted in an elegant, subdued blue on a lustrous body. The apocryphal Chenghua base mark is written in six-character standard script within a double circle in underglaze blue. The theme on the bowl illustrates the legend of Qixi (the Seventh Night), with magpies making a bridge for Niulang (Cowboy) and Zhinu (Weaver Girl) on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. Since ancient times, maidens compete with each other in needlework and make offerings to Heaven on the night of Qixi, praying for wisdom, skill at feminine crafts and happy marriage. This bowl, with its unique motif, was most probably potted for the purpose of holding food offerings at the Qiqiao Festival in the Palace. As a representative example of the output during the An family tenure at Jingdezhen, this bowl should be dated quite precisely to the last few years of the Kangxi reign and before 1727 when the An family were dismissed.

A dish, decorated in doucai style, is of the following Yongzheng reign, but the style of the special reign mark identifies it as belonging to the short period overseen by the An family (19). The interior of this dish is painted with a central medallion depicting a mythical horse galloping over a turbulent sea, its back supporting a ribboned book on a saddle cloth, against craggy rocks rising from breaking waves, surrounded by a double-line band. The exterior is embellished with swirling waves divided at each cardinal point with a boulder. This depiction of the “dragon horse carrying a book on its back” motif most likely derives from the fables of hetu and luoshu. According to ancient Chinese legend, a dragon horse once emerged from the Yellow River during the legendary Fuxi period, carrying on its back a script named hetu. The legendary Emperor Yu of Xia, who was famous for his ability to control rapid waters, also spoke of a mythical turtle from the River Lou, which had the luoshu script inscribed on its back. Both hetu and luoshu were regarded as “Divine Treasures bestowed from Heaven”, and from hetu, Fuxi was able to invent the trigrams from which Chinese culture and its writing system originated. The hetu and luoshu are thus taken as propitious omens of a prosperous time. Emperor Yongzheng was a devout believer in auspicious objects, and this present dish epitomises his passion for good fortune and auspiciousness. The base mark is inscribed in a three-line six-character standard script format, following the style of the late Kangxi period. While the Qing imperial court replaced its emperors in succession, artisans at Jingdezhen, responsible for inscribing seal marks, might not have been replaced concurrently with the reign change. It is most likely that the same experienced calligraphist would have continued using the styles and the marks of the preceding reign until informed otherwise by the new emperor. As a natural and logical progression, the style of reign mark used in the late Kangxi and the early Yongzheng period bore close resemblance. The three-line six-character standard script within a double circle format of the present piece is atypical, as demonstrated by the manner in which the word “清” (Qing) was written: the horizontal stroke on the “月” ( yue) radical has been replaced by a vertical stroke, making it look like the character “円” (dan) (6-J). Reign marks featuring this way of writing “清” also appeared on some porcelain wares from the late Kangxi period, and extant samples can be found in private and public collections. This suggests that reign marks written in this format could have been inscribed by the same men working across the two reigns, corresponding to the tenure of the An family discussed above. The illustration and craftsmanship of the present dish, enamelled in a brilliant doucai style, closely resemble those of the Kangxi reign, making it clear that these were a continuation from that period. The usual subtle and elegant character, typical of mid to late Yongzheng doucai wares, had not yet emerged. Given that Yongzheng’s reign lasted only a short span of thirteen years, it is usually difficult to ascribe specific dates to pieces fired during his time. Hence the present dish, which can confidently be ascribed to the early Yongzheng period, i.e. pre-1727, is of academic significance.

It is often said that imperial Kangxi porcelain set the standard for later supervisors and potters working at the Imperial Porcelain Factory in Jingdezhen. Indeed, this could only have been accomplished through the farsightedness and taste of the Kangxi emperor and his administrative, design and technical teams in both Beijing and Jingdezhen. The pieces discussed above are only some of the numerous representative examples extant in collections in Hong Kong, China and overseas. It is hoped that further research relating to a specific group of imperial Qing porcelain, in regards to their historical background, identifiable key people responsible for production, together with their designated recipients, will be fruitful and will narrow down the dating range of the subject pieces, instead of merely attributing them to specific reign periods indicated by their base marks.

1 Wang Guangyao, “The Establishment and Ending of the Qing Imperial Porcelain Factory”, Ancient Chinese Imperial Kiln System, Beijing: Forbidden City Press, 2004, pp. 158–175.

2 Wang, ibid., pp. 158–161.

3 According to memorials presented to the Yongzheng emperor, dated respectively fourth moon of the third year and third moon of the fifth year of the Yongzheng reign. The two memorials are kept at the First Historical Archives of China.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift