ALEXANDRA VON PRZYCHOWSKI

Curator for the Arts of China and the Himalayan Region, Museum Rietberg

HOUSING AN EXCELLENT collection of arts from Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Ancient Americas, the Museum Rietberg in Zurich is one of the leading museums in Europe for the arts of non-European cultures. It is renowned among scholars, collectors and art lovers worldwide for its collection, as well as for its innovative and high-quality exhibition programme. The museum’s vision is to focus on the fascinating variety of artistic expressions and to raise interest in, and understanding of, foreign cultures, customs and beliefs.

The historical buildings

The museum is situated in one of the most beautiful parks of Zurich. Walking up the path through the landscaped garden, passing along exotic trees and native scrub, the visitor will catch sight of the main building of the museum, the Villa Wesendonck, built in 1856 and enlarged by a modern extension in 2007 (1). Two further stately mansions, both dating to 1886, complete the ensemble.

Villa Wesendonck is imbued with historical importance. It was the home of the family of Otto Wesendonck (1815–1896), a wealthy German silk merchant, who moved to Zurich via New York for business in 1851. Wesendonck bought a hill above the shore of Lake Zurich and commissioned Leonhard Zeugherr (1812–1866), the Swiss architect, to design a classical mansion in the style of the Villa Alani in Rome. The planning of the park and gardens was entrusted to a landscape architect, Theodor Froebel (1810–1893). Finally, in 1857, the family was able to move into the stately house, which soon became a magnet for the cultivated society of Zurich. Otto Wesendonck and his wife, Mathilde (1828–1902), welcomed and generously supported a great number of artists, intellectuals and scientists, including the composers, Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) and Franz Liszt (1811–1886), the Swiss poets, Conrad Ferdinand Meyer (1825–1898) and Gottfried Keller (1819–1890), and the German architect, Gottfried Semper (1803–1879).1

The couple became especially taken with Richard Wagner (1813–1883), the famous composer. They even bought a house adjacent to their villa and invited him to live there. Wagner stayed in this “Asylum on the Green Hill”—as he lovingly called it—for fifteen months. During this time, he not only worked on the manuscript of Tristan and Isolde, but also wrote a sketch for a project he never realised: an opera on an episode of the life of the Buddha, named The Victors. Having been introduced in 1854 to the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), Wagner began to read extensively about Indian religions, especially Buddhism. Some of these new ideas clearly influenced his later works. Soon, Wagner’s friendship with the lady of the house, Mathilde Wesendonck, grew—if we are to believe his letters—into an ardent love. This complicated situation eventually led to his departure from Zurich in August 1858, leaving behind his wife, Minna, and his muse, Mathilde.

A few years later, in 1871, the Wesendonck family returned to Germany and Adolf Rieter-Rothpletz (1817–1882), a textile industrialist from Winterthur, bought the estate. His son, Fritz Rieter-Bodmer, had two more houses built on the estate: the Park-Villa Rieter, in the German renaissance style, and the Villa Schönberg, in an English country house style with gothic elements. The estate remained in the hands of the Rieter-Bodmer family until after the Second World War, when it was purchased by the City of Zurich and turned into a public museum. The houses, including their outbuildings and the entire park, are today listed as cultural heritage sites. They have been beautifully preserved and carefully renovated, allowing minor interior adaption to be used as exhibition galleries, cafeteria, studios for education programmes, and offices. The well-kept park still preserves its old appearance of a late 19th century landscaped garden. Strolling through the green park, the visitor is able to experience a range of different landscape images: an alley canopied by large trees, a luxuriant forested hill, large connecting open spaces framed by densely growing plants and trees, and a scenic outpost overlooking the lake that allow for an extended view of the Alps.

The collection of Eduard von der Heydt and the founding of the museum

The Museum Rietberg was founded in 1952 by the City of Zurich to house the famous collection of non-European Art of Baron Eduard von der Heydt (1882–1964). In 1945, the city bought the estate of the Villa Wesendonck. When the citizens of Zurich decided in a public vote in 1949 to turn the mansion into a public museum, von der Heydt donated his entire collection to the city.

A native of Wuppertal in Germany, von der Heydt came from a respected collecting family. It is said that his fascination for Asian art resulted from his interest in the thoughts of the philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer. However, he soon broadened his view and began buying art from Africa, Oceania and Pre-Colombian America as well. Von der Heydt’s concept was ars una—”there is only one art”—as he believed that artistic creation can be found everywhere, in every century, on every continent. No other collector at the time collected in such variety: works from Japan, China, India, New Guinea, Cameroon, Congo, as well as paintings by Cezanne, Van Gogh and Picasso. His collection once included more than 3000 works of mostly non-European art.

Although von der Heydt never travelled to Asia or Africa, he bought artworks from respected dealers in Europe and the US. From the beginning of his collecting activity, he exhibited his works of art to the public. As early as 1922, he showed them in spaces within his private home in Amsterdam (2). In 1927, he opened a public cafeteria in Zaandvoort, a beach resort near Amsterdam. In this Museum Lunch Room (MULURU), he exhibited the art objects according to his idea of ars una: Indian statues facing African masks, Chinese Buddhas beside Romanesque Madonnas. In 1926, he acquired the Monte Verità in Ascona and enlarged the estate with a second modern hotel building. From 1930 onwards, he made the place his permanent residence, and in 1937, he even obtained Swiss citizenship. In this large building complex, von der Heydt hosted an illustrious array of guests, the elite of art, literature, music, theatre and dance. The houses were decorated with objects from his collection, again juxtaposing pieces from different regions of the world. He entrusted other parts of his extensive collection as long-term loans to various museums in Europe and the US, or had them exhibited in several shows. Between 1932 and 1941, the Arts and Crafts Museum of Zurich (Kunstgewerbemuseum) mounted a number of exhibitions on Indian, African, Oceanic and East Asian art, some of them drawing primarily on the collection of von der Heydt. This strengthened the ties between the collector and the City of Zurich, resulting in his decision to donate his collection of non-European art to the City of Zurich, while his European works of art went to the Von der Heydt Museum in Wuppertal. The nearly 1600 objects are still the main pillar of the Museum Rietberg’s present collection.

The history of the museum’s collection

Since the founding of the museum, the collection has grown substantially thanks to large-scale donations of important collections, as well as generous gifts and financial support from private and corporate sponsors.

At the time of the opening of the Museum Rietberg, the Chinese department only housed the von der Heydt collection, with its high-quality sculptures (3). The J.F.H. Menten Collection of more than 120 pieces of Chinese tomb figures and bronzes, which had been on loan to the Arts and Crafts Museum of Zurich since 1948, was then purchased and transferred to the new museum. In the 1960s and 1970s, the museum received the collections of the Rücker-Embden family of thirty-two ceramics, as well as Chinese paintings, bronzes and jades from the collection of Gret Hasler. A large and important group of 213 jade objects, including a great variety of finely carved pieces from the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, entered the museum in 1960. These were collected by Reinhard J.C. Hoeppli (1893–1973), the Swiss doctor and zoologist, who was Professor of Parasitology at a Medical College in Beijing from 1929 to 1942 and again from 1948 to 1952. Moreover, Hoeppli collected snuff bottles at a time when there was very little connoisseurship in this field. He was able to assemble a small, but exquisite, group, manufactured either as gifts for the imperial court or in the palace workshops.2

In the field of Chinese painting, the museum is greatly obliged to Charles A. Drenowatz (1908–1979), who donated his outstanding collection of more than 300 paintings in 1979 (see the article by Kim Karlsson in this issue). Drenowatz never went to East Asia, but assembled his collection during the 1950s and 1960s by buying from renowned dealers in Europe. He was especially interested in the literati paintings from the late Ming and the early Qing dynasty, but also collected ink paintings from the first half of the 20th century.3 Thanks to his gift, the museum now boasts several masterpieces, such as Gong Xian’s (circa 1617–1689) A Thousand Peaks and a Myriad of Ravines, Mei Qing’s (1623–1697) album, Magnificent Views of Xuancheng, as well as exceptional works by Fu Baoshi, Huang Binghong and Li Keran. A selection of these paintings is always on show in the Chinese galleries, rotating every four months.

In 1986, the museum received the generous bequest of forty-three archaic Chinese bronzes from Ernst Winkler (1902–1985), who collected primarily in Hong Kong during his time as a businessman in Asia. The precious collection holds excellent bronze ritual vessels from the Shang ( circa 1600–1100 BC) and Zhou (circa 1100–256 BC) dynasties (4). Some outstanding artworks of China’s Bronze Age came to the museum thanks to the generosity of Pierre Uldry and his wife, Alice. Between 1979 and 2000, he purchased five exceptional pieces for the museum, including a giant early Zhou ding tripod and an impressive Shang nao bell. Pierre Uldry was not only an enthusiastic supporter of the museum, but also a passionate collector. He started buying Chinese cloisonné before the quality of this art form was widely appreciated, and was able to assemble a unique collection of early pieces of the highest quality (5), including a large imperial dragon jar bearing a Xuande (1426–1435) mark, widely considered the most important early cloisonné object (along with its corresponding piece in the British Museum).4 Part of this important collection is on long-term loan in the Museum Rietberg.

At the start of 2012, the Chinese department gratefully received its most dramatic augmentation when the Meiyintang Foundation placed 650 works of Chinese ceramics, dating from the Neolithic period (circa 6500–1600 BC) to the Song dynasty (960–1279), on permanent loan in the museum (6). Beginning in 1994, the renowned Meiyintang Collection of Chinese ceramics and porcelain assembled by two brothers over a period of five decades, was shown in several exhibitions and published in successive volumes. In 2003, Gilbert Zuellig, the collector of the earlier works up to the Song dynasty, decided to transfer the majority of his collection to a foundation with the purpose of preserving it as an ensemble and making it accessible to the public. For the last seven years, these artworks have enriched the China galleries of the Museum Rietberg, turning the museum into a Mecca for ceramic lovers (7).5

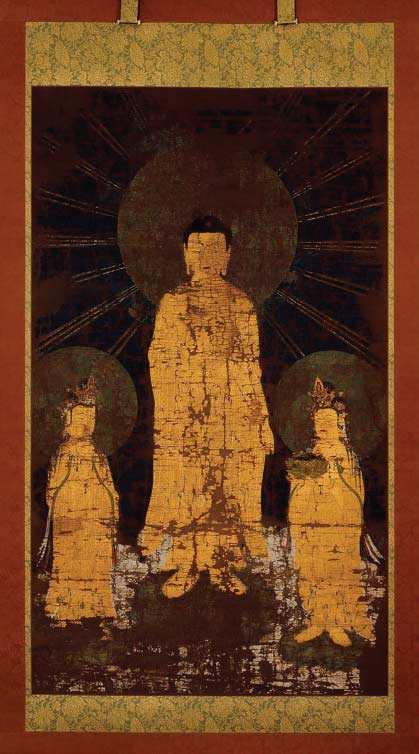

The Japanese holdings (8) also have their roots in the collection of Eduard von der Heydt (9), who acquired his first Chinese and Japanese artefacts from the estate of Raphael Petrucci (1872–1917), the Franco-Belgian Sinologist. Although not an expert in Japanese art, von der Heydt relied on the fact that the collection was of high quality due to its provenance. However, except for a few good Buddhist paintings, the 109 Japanese objects, that include sculptures, tea wares and secular paintings, are of lesser artistic importance. The first major enhancement of the collection came in 1957 in the form of the donation of over 700 woodblock prints and books by Willy Boller (1883–1959), who started collecting Japanese prints when he was a student in Paris in the 1920s. He never went to Japan, but forged his connoisseurship in Japanese woodblock prints from contemporary publications in English and French. Starting in the late 1920s, he also organised exhibitions of Japanese prints in Zurich. The quality of his collection is mixed, but is considered a valuable source for the understanding of the state of knowledge of, and connoisseurship in, Japanese woodblock prints in Switzerland in the first half of the 20th century.

The next significant donations of Japanese art to the Museum Rietberg came in the early 1960s from Julius Mueller (1886–1970). An employee of Volkart Brothers, the international trading company based in Winterthur, Mueller first worked at the company’s branch in India before being dispatched to Japan in 1914. During the First World War, Mueller remained in Japan, formed a family with a Japanese woman and immersed himself in the study of Japanese language, culture and the arts. After his retirement, he returned permanently to Switzerland where he engaged in the promotion of cultural exchange between the two countries. Mueller used his abundant financial means to assemble a discerning collection of Japanese art comprising Haniwa figures, Buddhist paintings and sculptures, Edo period (1603–1868) paintings and woodblock prints of the early masters. Many of the museum’s highlights belong to the group of 246 works that he donated in various installments between 1962 and 1965.

Mueller collected mainly in Japan, where he was assisted by Heinz Brasch (1905–1995), his colleague and close friend. Brasch was born in Japan, the son of a German professor and a Japanese woman. He gained his familiarity with woodblock prints and later paintings through his father, who was a passionate collector of prints. Through his employment at Volkart Brothers, Brasch built up a strong connection to Switzerland and finally settled in Zurich with his family after the Second World War. He became a close friend with Elsy Leuzinger (1910–2010), the second director of the Museum Rietberg, and consulted her in organising an exhibition of Japanese prints and paintings, for which he wrote the catalogues. Brasch also published widely on Kyoto, his hometown, as well as on Nanga and Haiga, the first such studies in German. There are 163 of his paintings and woodblock printed books in the museum’s collection.6

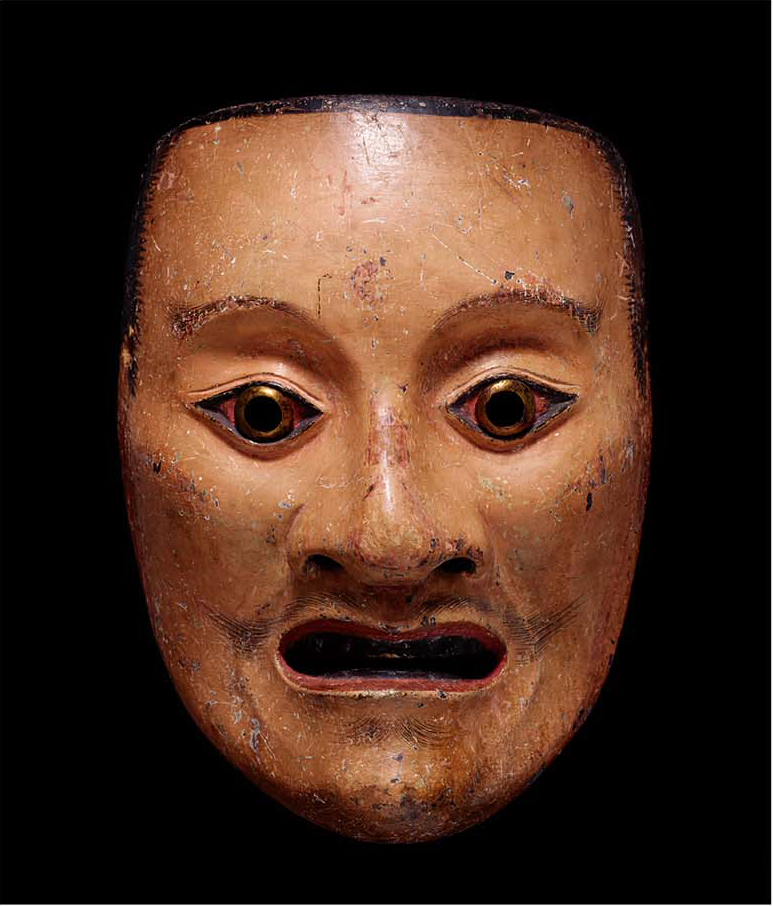

The highlight of the Japanese collection is undoubtedly the group of thirty-four outstanding Nō masks, donated to the museum in 1991 by Balthasar and Nanni Reinhart (10). The collection was assembled by Balthasar’s father, Georg Reinhart, who hailed from the renowned industrialist and art collector Reinhart family of Winterthur. The masks once belonged to the Toyama branch of the Maeda clan, feudal lords of Kaga province (present-day Kanazawa Prefecture) and great patrons of the Nō theatre. They were brought to Europe in the early 1900s and Reinhart bought them through the introduction by Ernst Grosse (1862–1927), one of the pioneers of East Asian art history in Germany and a close acquaintance of Hayashi Tadamasa, the famous Japanese art dealer.7

Over time, the Japanese holdings grew steadily through gifts, bequests, acquisitions and permanent loans. Most noteworthy among the permanent loans is the extraordinary collection of over 300 kyōka-surimono, collected by the Swiss-based, Italian artist, Marino Lusy (1880–1954). This collection, which includes a substantial number of rare and exquisite pieces, was donated to the Museum of Design Zurich and transferred on permanent loan to the Museum Rietberg in 2005 (11).8 Another remarkable collection of about 250 surimono, focusing on the less known genre of the Shijo school, entered the museum’s collection in 2018 as a gift of Gisela Müller and Erich Gross. Japanese religious art, Nō masks and costumes, as well as paintings and prints, are shown in regular rotations in two dedicated galleries of the museum.

Himalayan and Tibetan art became a major focal point of the museum, with the permanent placement of around 200 bronze sculptures by the Berti Aschmann Foundation in 1995 and 2004. Berti Aschmann (1917–2005), the Zurich collector, assembled this magnificent group of sculptures over a period of forty years. The collection provides a comprehensive survey of the development of Buddhist bronzes in India, Nepal and Tibet, beginning with pieces from the Swat valley dated to the 7th century, from Kashmir (12) and India’s Pala dynasty, to the classical style of Tibet. A group of fourteen exquisite examples of the Tibeto-Chinese bronzes, manufactured in the imperial workshops in China, is quite outstanding (see the article by Christian Boehm in this issue). Aschmann paid particular attention to the charisma and beauty of the statues as expressed by their faces. One specialty of her collection is the emphasis on statues of female deities (13), comprising no fewer than thirty-four individual works.9

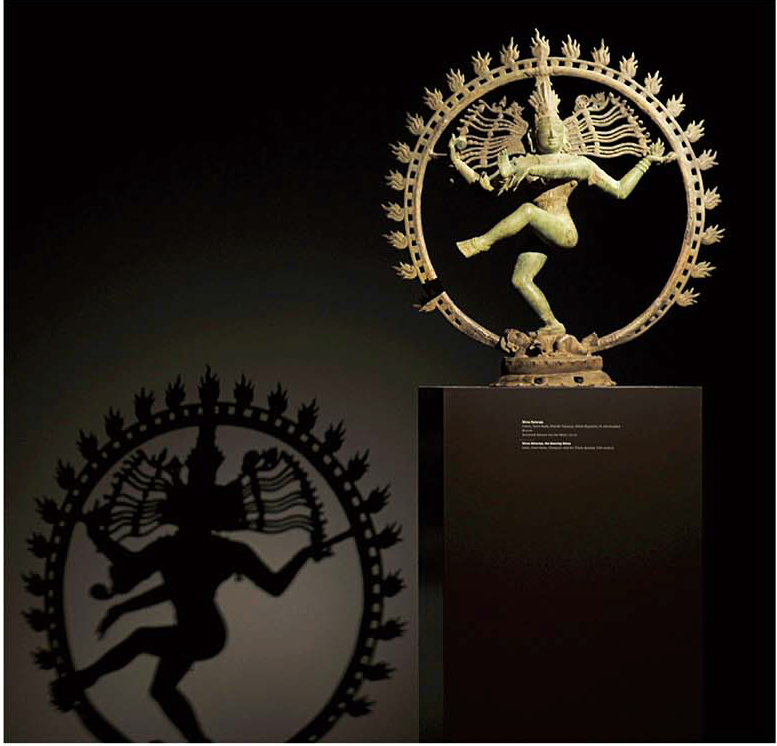

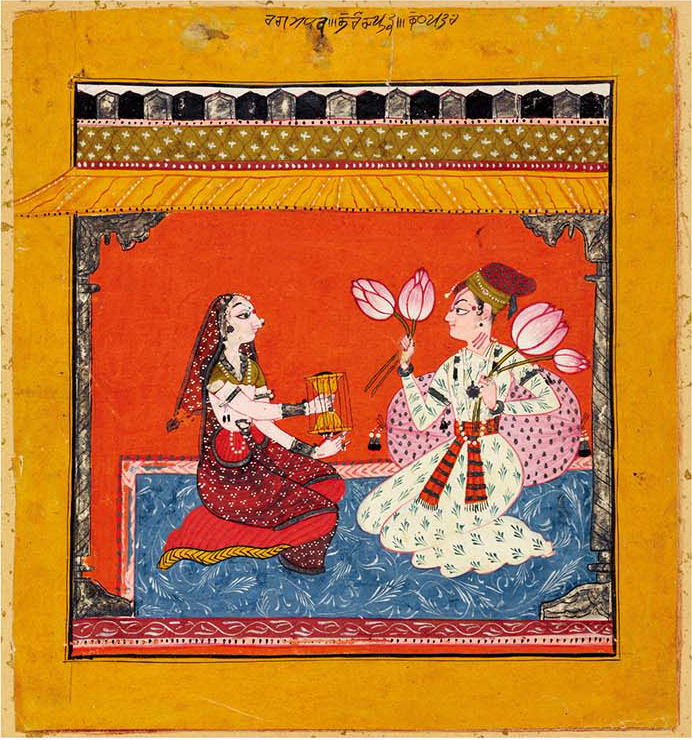

The fine collection of Indian sculptures from von der Heydt (14) was enlarged in 1971, when the Alice Boner Collection was donated to the museum (15) and the permission of the Indian Archaeological Survey was obtained to transport the pieces from the collector’s home in Varanasi to Zurich. Alice Boner (1889–1981), the Swiss artist, settled in Varanasi in 1936, where she continued her work as a sculptor, but also studied Indian art and painting. Her seminal art historical work, as well as her engagement in propagating Indian music and dance, made her an important cultural mediator. Today, the Museum Rietberg houses most of her collection of Indian sculpture and approximately 650 Indian miniature paintings (16), as well as her personal and artistic archive, including sculptural works, drawings, paintings, correspondence, scientific writings and more than 30,000 photographs. Her legacy was the subject of a research project, resulting in an exhibition dedicated to her life and work, presented in Bombay (Mumbai), New Delhi and Zurich.10

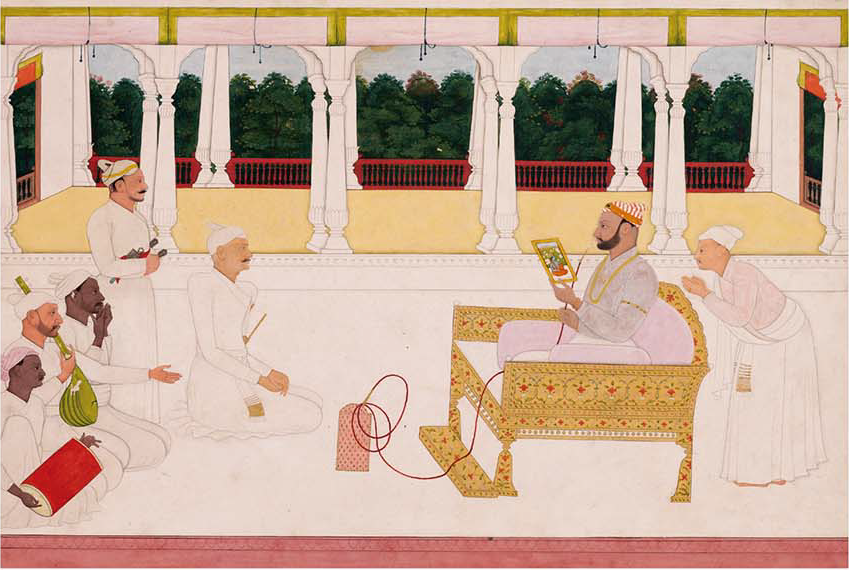

The gift of the Alice Boner Collection of Indian paintings laid the foundation for one of the major focal points of the Museum Rietberg. Due to the commitment of Eberhard Fischer, the third director of the museum, the collection has grown steadily in size and importance. Several donations of larger collections, as well as individual purchases and gifts by a number of supporters, have ensured that the Indian painting department has one of the most important holdings of Indian paintings worldwide. In 2001, the museum received approximately 250 paintings from Horst Metzger,11 the German collector, while Danielle Porret has donated forty-four examples over the last nine years. Thanks to generous sponsors, the museum has also been able to make a large number of complementary acquisitions in the art market (17), so that the Indian painting collection now totals more than 1800. These are presented in three exhibitions each year in a dedicated exhibition space in the Parkvilla Rieter.

Over the last twelve years, the Indian department has opened to new fields of art. In 2009, it received a large collection of some 1500 pieces of Indian textiles, collected mainly in Gujarat in the mid-20th century by Eberhard Fischer. The objects allow an overview of textile production in traditional India and show a great variety of the techniques and the creativity of weavers, dyers, painters, printers and embroiderers.

The sculptural art of the Adavasi people, the tribal societies of India, are now well presented through three large donations and acquisitions (see the article by Johannes Beltz in this issue): some 350 tribal bronzes from South India from the collection of Heidi and Hans Kaufmann in Vienna; approximately sixty tribal bronzes from Central India donated by Jean-Pierre and Dorothea Zehnder; and a group of ninety-two sculptured string instruments collected by Bengt Fosshag.

The rather small collection of Southeast Asian art in the Museum Rietberg, most of which comprises sculptural works from the donation of von der Heydt, contains some very fine Khmer and Champa sculptures (18).12 The bestowment of the collection of Toni Gerber, the Swiss gallerist, in 2002, led the museum to explore new fields of artistic creation. The large holdings of small, but interesting, objects consist of three groups: 600 votive plaques of fired or air-dried clay, dating from the 10th to the 19th century, from Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand; nearly 400 small metal figurines, mostly showing scenes from the life of the Buddha Shakyamuni, made for votive stupas in Burma in the late 19th and the early 20th century; and around 350 ceramic vessels from a wide area in Southeast Asia. In 2006, the museum also received forty-five Javanese Wayang kulit shadow play figures, dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, from Paul Stohler.

Eduard von der Heydt, the founding donor of the museum, never collected art from the Near and Middle East, with the exception of several carpets. Two more donations of carpets from Robert Akeret in 1959, and Erwin and Hilde Luck in 1988, have formed a group of some 160 carpets from Persia (Iran), Turkey, the Caucasus, Eastern Turkestan and Egypt. Recently, an outstandingly well-preserved collection of Persian garments, embroideries and printed fabrics, collected by Emil Alpiger in the late 19th century in Persia, entered the museum’s collection.

Objects from the area now constituting modern Iran now represent the focus of the art collection of the Department of the Near and Middle East. Rudolph Schmidt, the famous art collector, gave a collection of some 200 ancient bronze objects from Luristan, dating from 3000 to 1000 BC, to the museum in 1971. It includes some of the oldest pieces in the museum’s holdings. Ceramics, manuscripts, and some newly acquired excellent examples of lacquer objects from the 18th century Qajar period complete the collection.

One of the Museum Rietberg’s strengths is its high-quality collection of sculptural arts from Africa. As early as the 1920s, von der Heydt realised the high artistic quality of the wood sculptures from Western and Central Africa and started collecting these items for their aesthetic value. He was deeply impressed by the manifestation of the idea of the noble human being in these artworks. More than 300 sculptures had entered the museum by 1952 (19) and another fifty-seven works, collected by Han Coray (1880–1974), the Swiss gallerist, between 1919 and 1928, were transferred to the Museum Rietberg from the Museum of Design in Zurich. The Department of Africa has since grown through purchases and donations (20). More than 750 objects, collected and documented by Hans Himmelheber (1908–2003), the art ethnologist, have been brought together in the museum’s collection, the majority of donations from Barbara and Eberhard Fischer and members of the Himmelheber family. The groundbreaking research by Himmelheber on the identification of individual artists in different regions in Africa is held in high esteem at the Museum Rietberg. Several exhibitions, focusing on different ethnic groups or regions, have explored the individual hand of the artist.

Von der Heydt collected the arts of the Americas to a lesser degree. However, after the founding of the museum, Elsy Leuzinger actively started to acquire objects of Mesoamerica and South America. Today, the museum boasts an exquisite collection of art from the Northwest Coast, Mexico and Peru. Several large exhibitions have highlighted art from the Americas, especially from different cultural periods of Mexico and Peru. These have led to a fruitful co-operation between the museum and archaeologists and specialists worldwide.

Oceanic art is represented in the Museum Rietberg by a fine group of objects that von der Heydt bought in the 1920s and 1930s, including pieces of extraordinary quality. The most “exotic” field in the museum is a local one, comprising a group of 162 Swiss masks worn during carnival and other traditional seasonal festivals in the mountain valleys. The collection was assembled almost entirely by von der Heydt and is the most comprehensive collection of Swiss carnival masks in Switzerland.

A newly established department in the museum is dedicated to photography. The collection includes works by renowned photographers from Africa, Asia and Europe, as well as field photography and historical images of items in the museum’s collection. The photographic archive of scholars and researchers closely linked to the museum—Alice Boner, Hans Himmelheber and Elsy Leuzinger—constitute an important part of this collection.

In addition to eight curators attending to the different regional departments, the museum instituted a position for provenance research more than ten years ago. The first results of the research have led to a major exhibition in 2013 on Eduard von der Heydt, his life and collection policy.13 Other temporary exhibitions, displayed in the premises of the permanent collection, introduced different facets of provenance research. In 2013, a show focused on Alfred Flechtheim (1878–1937), the art dealer, and his ties to the museum’s collection of Oceanic art. The exhibition, “The Question of Provenance”, in 2019 discussed a variety of thematic fields that arise from provenance research. All data from the provenance research are included in the online data bank and can be consulted by museum visitors.

Exhibition activity

Since 1972, the museum has regularly organised special exhibitions, starting in off-site exhibition spaces spread across the city of Zurich. In 1985, the museum was able to build a two-storey underground exhibition space of 1100 square metres, allowing larger exhibitions to take place on its premises. A new large extension opened to the public in 2007, increasing the exhibition space by 125 per cent. The spacious halls, equipped with the latest technology and providing the best conditions for the artworks, impress with their clarity and restrained elegance. The architects, Adolf Krischanitz (Vienna) and Alfred Grazioli (Berlin), constructed the underground building, thus leaving the exterior of the villa and the park unaltered. Visitors enter the building through a glass pavilion and proceed into the foyer with its distinctive agate ceiling and a work by the contemporary artist, Helmut Federle. From here, they descend to the two underground levels, each comprising 1300 square metres and connecting the entrance with the historic Villa Wesendonck. The upper level houses the collection of East Asian and African art, as well as a gallery for temporary exhibitions. The lower level provides a large open plan space. This structure enables every special exhibition to be presented with a new interior design, imbuing each show with an individual look and ambiance.

The extension has also allowed for an open storage display. The bigger part of the museum collection, excluding light sensitive objects on paper or textiles, is visible to the public during regular opening hours. This enables visitors and specialists alike to contemplate and study the holdings of the museum at all times. Along with open access to the online collection—albeit still a work in progress—the open storage is part of the museum’s policy of transparency. In the new exhibition rooms, the museum organises temporary shows on a regular basis of two to three large and three smaller exhibitions per year. Additionally, Indian painting is displayed in three thematic shows each year, drawing mainly from the museum’s own holdings, but also including loans from public or private collections.

Since the 1980s, the museum has co-operated with partner institutions worldwide, including the following early exhibitions: in 1986, “Dian—A Vanished Kingdom in China” with archaeological finds from Yunnan province, later travelling to museums in Cologne, Vienna, Berlin, Stuttgart and Rome; in 1989, the Oxus culture in cooperation with the Academy of Science in Tajikistan and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg; and in 1993, Helmut Brinker, Professor for East Asian Art History at the University of Zurich, curated the groundbreaking exhibition, “Zen—Masters of Meditation in Images and Writings”, in co-operation with the Kyoto National Museum and the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan.

The Museum Rietberg has also been the partner to a number of important international exhibitions, such as “Buddha’s Paradise—Treasures from Ancient Gandhara, Pakistan” in 2009, and “Osiris—Egypt’s Sunken Mysteries” in 2017, the latter drawing more than 100,000 visitors. We have also organised a number of shows, that were passed on to other partner museums, such as: “Wonders of the Age: Master Painters of India, 1100–1900” (2011) and “Eccentric Visions: The Worlds of Luo Ping” (2010) to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; “African Masters” (2014) to Bonn, Amsterdam and Paris; and “Return of the Buddha: The Qingzhou Discoveries” (2002) to Berlin and the Royal Academy in London.

It has always been an ambition of the Museum Rietberg to present individual artists and their works. Two landmark exhibitions were “Master Painter of India” in 2011, presenting the most important Indian painters and their best works in one show, and “African Masters” in 2014, working out the individual hands and styles of great sculptors from different generations and parts of West Africa. The museum has ventured to present several monographic shows on traditional Asian artists—each of them for the first time in the West. In 1997, an exhibition focused on the innovative 8th century Indian painter, Nainsukh of Guler. The famous 16th century Japanese artist, Hasegawa Tōhaku, made a lasting impression on the museum’s visitors in a great show in 2001, including his masterpiece, Pine Forests, which is often considered to be the most important painting in Japan’s art history. Another major exhibition dedicated to a single Japanese artist took place in 2018. “Rosetsu—Ferocious Brush” presented for the first time ever the entire set of sliding doors that the artist painted in 1786 for the Zen temple Muryōji in Southern Wakayama Prefecture. In 2009, the museum staged the first monographic show worldwide on the eccentric 18th century Chinese painter, Luo Ping, presenting some of his masterpieces from Chinese, Japanese and Western museums, that had never been publicly shown before.

A hallmark of the Museum Rietberg is the holding of cross-cultural exhibitions, exploring one specific topic in different societies across the world. Developed as a joint curatorial effort, the museum presented “Oracle—A Glimpse into the Future” (2000), “The Art of Love—Pleasure and Suffering for Love in World Art” (2003), “Mysticism” (2012), “Mysteries of the Cosmos” (2014) and “Garden Cultures” (2016). This spring and summer, the museum will narrate the cultural and relevant history and symbolism of the mirror (2019).

In its broad spectrum of special exhibitions, the Museum Rietberg has addressed archaeological topics, such as the Peruvian cultures of Chavin (2012) and Nasca (2018); told stories of early global exchange and trade, such as the production of ivory carving in Sri Lanka for the Portuguese court in the 16th century (2010); the mutual cultural appropriations between Persia and Europe in the 17th century (2013); and presented wide-ranging themes in a didactic way, such as in the show on Buddhism in 2019.

Raising awareness of diverse cultures and ways of thinking, as well as of the interconnectedness of global societies, is an important issue in the work of the museum. Alongside the exhibition programme, the museum offers a wider range of activities, including 300 to 400 workshops a year catering to primary and secondary school students, fostering inclusiveness for visitors of all ages and social background. More than 1000 public and private guided tours per annum introduce visitors to in-depth content. On Sundays, the open atelier invites the young and old alike to experiment with artistic techniques. A Japanese tea master regularly hosts tea ceremonies in an authentic tea room, while concerts presenting celebrated Indian singers and solo musicians are organised periodically. Attracting 100,000 visitors a year, the Museum Rietberg is a flagship institution showcasing Zurich’s cultural engagement and diversity.

1 Axel Langer and Chris Waldon, Minne, Muse und Mäzen: Otto und Mathilde Wesendonck und ihr Zürcher Künstlerzirkel, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2002.

2 Robert Hall, Chinese Snuff Bottles, Masterpieces from the Museum Rietberg Zurich, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 1993.

3 Chu-Tsing Li, A Thousand Peaks and a Myriad Ravines: Chinese Painting in the Charles A. Drenowatz:. Collection, Ascone: Artibus Asiae, 1974; and Chu-Tsing Li, Trends in Modem Chinese Painting, Ascone: Artbus Asiae, 1979.

4 Helmut Brinker and Albert Lutz, Chinese Cloisonné: The Pierre Uldry Collection, New York: The Asia Society Galleries, 1989.

5 Alexandra von Przychowski, Chinese Ceramics: The Meiyintang Collection in the Museum Rietberg, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2018.

6 Nara Prefectural Museum of Art, Masterpieces of Ukiyoe from the Rietberg Museum Zurich, Nara: Nara Prefectural Museum or Art, 1993.

7 Brigitte Bernegger, No-Masken in Museum Rietberg: Die Schenkung Balthasar und Nanni Reinhart, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 1993.

8 John T. Carpenter, Reading Surimono (with a catalogue or the Marino Lusy Collection), Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2008.

9 Helmut Uhlig, On the Path to Enlightenment, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 1995; and Heidi von Schroedcr-lmhor, Schritte zur Erkenntnis, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2006.

10 Andrea Kuratli and Johannes Beltz, eds, Alice Boner: A Visionary Artist and Scholar across two Continents, New Delhi: Roli Books, 2004.

11 B.N. Goswamy and Eberhard Fischer, The Horst Metzger Collection in the Museum Rietberg, New Delhi: Kiyogi Books, 2018.

12 See Jan Fontcin, The Art of Southeast Asia: The Collection of the Museum Rietberg, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2007.

13 Eberhard Illner, ed., Eduard von der Heydt: Kunstsammler; Bankier, Mäzen, Munich: Prestel, 2013.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift