MARIA KAR-WING MOK

Museum Director, Hong Kong Museum of Art

The China Trade Collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Art

China Trade art constitutes a strong pillar among the four core collections of the Hong Kong Museum of Art (HKMoA). Totalling approximately 1300 artworks, the collection comprises works in oil, watercolour, gouache and print as well as a small number of maps, all focusing on depictions of the Guangdong and South China coast from the late 18th to the third quarter of the 19th century. Emerging in large quantities when the China trade flourished, these works were first produced in Canton (Guangzhou) when the city was the sole port of access to China for foreign trade from 1757 to 1842, and later in other trade ports, such as Shanghai and Hong Kong.

The collection may be divided into two main categories with respect to the artists: works by Chinese artists and by Westerners. The first category comprises what is widely known as trade paintings or export paintings—port scenes, personal portraits, portraits of shipping, illustrations of Chinese life, such as local industries, streets, costumes and festivals, as well as the rather scientific botanical studies and the less scientific flower-and-bird genre. These trade paintings were produced by Chinese artists for sale to Western customers, who took them home as souvenirs of their venture in the Orient. The other category is composed of artworks by expatriate and travelling artists, who recorded their sojourns and brief visits in paintings, drawings and prints. These two categories are often termed under the larger, more general nomenclature “China Trade” pictures. Because of its nature and target audience, the collection is a pictorial archive that contains a vast amount of aesthetic, topographical, historical and sociocultural data of the region, but, somehow, the significance of these paintings has only been recognised by a small group of collectors, scholars and art historians.

Perhaps one of the reasons for this lack of interest lies in a misconception. China Trade art, in particular trade paintings or export paintings of the first category mentioned above, have always been regarded as a commodity, produced on an assembly line. It has been commonly held that trade paintings were mostly produced by copying templates. Although very few textual references describe the exact technique employed at the time, those who visited the Canton workshops and witnessed the manufacturing of trade paintings, or other kinds of export art, took particular note of painters doing all sorts of “copying”,1 as well as a factory type of production. For example, one craftsman might paint the sky or background on a painting, another might add houses, and another inserted the boats or trees, and so on. 2 The fact that most of these paintings are, at a glance, identical in subject, composition, colour scheme and detail may support the impression that these works were executed in large quantity on a production line; a small number of works might have been executed with great exactness while others were more the result of careless reproduction. Consequently, these work have been labelled as a shoddy commodity-lacking artistic refinement and historical significance. In recent years, the HKMoA has been engaged in research that helps defy this notion and redefines the nature and features of trade or export paintings.

The Chinese “Apprentice” and the Western “Master”

A renewed comprehension of Chinese Export painting comes from a deeper understanding of the fundamental difference between works of the two categories, i.e. export paintings by Chinese and works by expatriate Western artists. This was the subject of an exhibition and accompanying catalogue3 in 2011, titled “Artistic Inclusion of the East and West—Apprentice to Master”, and a subsequent conference paper in 2013.4 This study focused on a review of major stylistic features and important traits of Western art in Chinese Export painting. Many of these works resorted to emulating, in various degrees, compositions or themes from their Western counterparts. Some managed the fundamentals and went further to challenge themselves with more difficult elements: they produced engaging trials with meaningful errors. Others adhered to native genres and presentation, with minimal Western touches: their works were less “Westernised”, but nonetheless appreciated by their Western clientele. There are also Chinese works technically equal to those of Western professional artists, if we judge them based on the Western artistic convention and values.

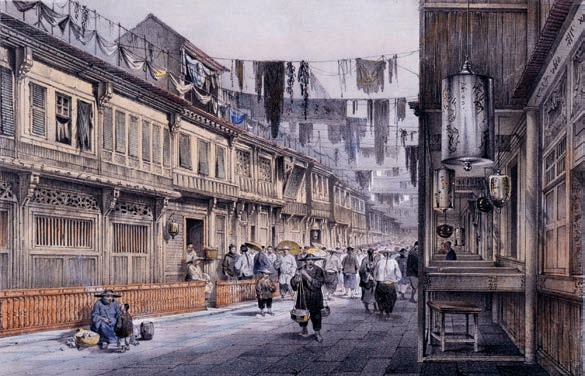

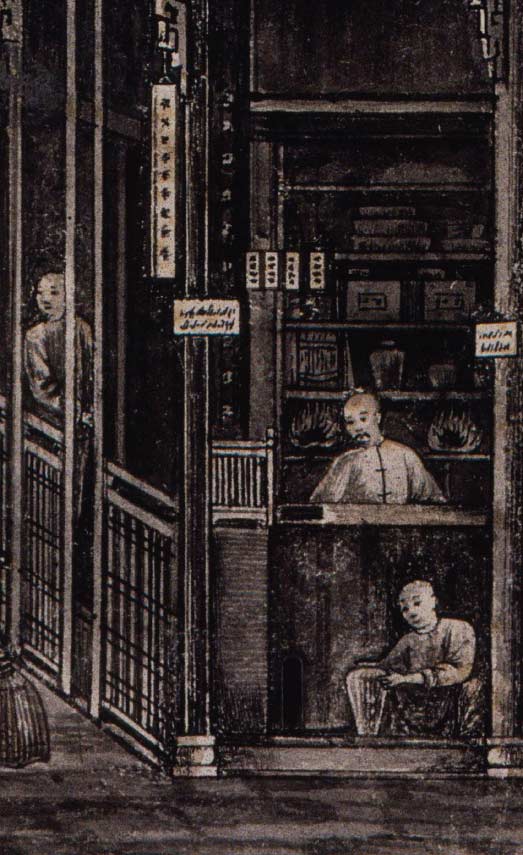

The exhibition illustrated the role of Western art traditions in Chinese Export painting and their interaction through a display of Chinese Export paintings alongside works by Western artists, particularly those who had been to China. For example, a Chinese ink drawing (1) is paired with a lithograph based on the work of a Western traveller (2), each with the same subject matter of Canton street shops. In the first (1), the liveliness of the street is painstakingly rendered to the point where the articles on sale inside the shops, and even labels on packages, are recognisable (3). Works by visiting artists, on the other hand, may be less weighted in detail, but serve as testimonials of the places visited. For instance, the pictorial memoir of the painter Barthelemy Lauvergne (1805–1871), who visited Canton in the 1830s,5 demonstrates that he was apparently struck by how terribly crowded New China Street was: he gives greater emphasis to the shoulder-rubbing hawkers and intentionally creates a dramatic recession, that narrows the street to highlight its suffocating space (2). The Chinese painter focused on producing a neat and carefully composed, detail-oriented, almost pictorial, record for his client. Lauvergne, on the other hand, was less concerned about what was on sale in the shops or how Chinese lanterns should look, than in capturing his experience. This was a common feature: the Chinese work is a record of detail, whereas the Western work is an emotional memoir.

Market Preference: Hybrid Art

Our study for the above exhibition determined that the difference between the artworks produced by the Chinese and Western artists fundamentally came down to different market demand. The Chinese artists were producing hybrid works—not Chinese, but not completely Western—that gave them their market niche. An exemplary work in this hybrid style is an interior scene, Receiving Guest (4). It clearly adopts Western linear perspective in an attempt to create a convincing space of accurate proportions to create a sense of depth. The lines of the arch (at the top centre) narrow to a vanishing point at the horizontal scroll on the wall outside. However, if the lines of the ceiling, the windows and the floor are joined, different eye levels and vanishing points appear (5). Anyone familiar with Western perspective may judge this Chinese work defective. However, those acquainted with the perspective used in Chinese traditional fine art would immediately relate to the multi-perspective experience offered by traditional Chinese ink painting. If judged solely from the standard of Western art, most export paintings, like this one, could be considered attempts to imitate Western works with thought-provoking “flaws” in composition, space, chiaroscuro, etc. For today’s audience, these works might seem gaudy and substandard, but the contemporary market preference for this hybrid style has been overlooked.

Apart from a few artists, whose works match the ideals and methods of the West (6, 7), the majority of Chinese Export “imperfect” works were rather popular, implying that even though the Western market held high regard for their own artistic tradition, they did not seem to mind these technical imperfections. This is quite intriguing, considering the rare occasions that any market is ready to spend on “flawed” products. Research on stylistic features of Chinese Export painting has been expanded to review relevant textual references, particularly the contemporary writings of Westerners who visited China, and illustrate how this idiosyncratic commodity was perceived and received by Western customers during the late 18th to the mid-19th century.

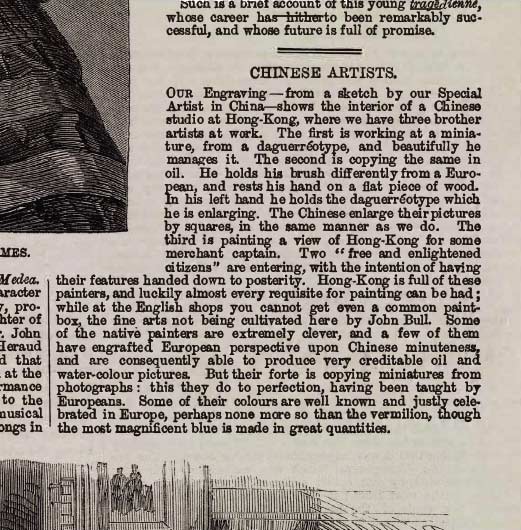

The non-hybrid works by Chinese artists, like Lamqua (1801/1802-?)6 and a few others, might seem a logical choice for Western customers, but the vast number of export paintings in hybrid style, that were bought and shipped out of China, suggests that at least some of the Western market had also fallen for those works marked by their gaudy colour, minute brushstrokes and a naïve or flawed perspective. The market would have rejected these hybrid works, had everyone chosen to paint like Lamqua. In fact, we find in textual excerpts that the market preference was rather discernible, with many such commentaries coinciding with the stylistic quality of export paintings, still visible on extant items today. The fineness, for instance, achieved by Chinese brushwork is a feature that received many compliments. A further example of market demand was recorded in The Illustrated London News (8, 9): “Some of the native painters are extremely clever, and a few of them have engrafted European perspective upon Chinese minuteness, and are consequently able to produce very creditable oil and water-colour pictures.”

Offering a matrix of Western aesthetic features, such as “perspective”, with those of the Chinese, such as “minuteness”, was an “extremely clever” act: it was a tactic, a deliberate decision to please buyers. Judging from the comments of contented customers, the tactic worked very well, as described in my study and analysis of these marketing tactics published in 2014.7

Painted Details: Key to Answers

Among many differences between the Chinese and Western artists, that lead to a clearer picture of the China Trade art market, is another significant feature: the emphasis on rendering detail, and the historical meaning of such detail, in the Chinese works. Details carried meanings other than artistic or technical preference and choice. In subsequent research, we have proven that the detail in a painting is the key to unlocking many mysteries in China Trade art.

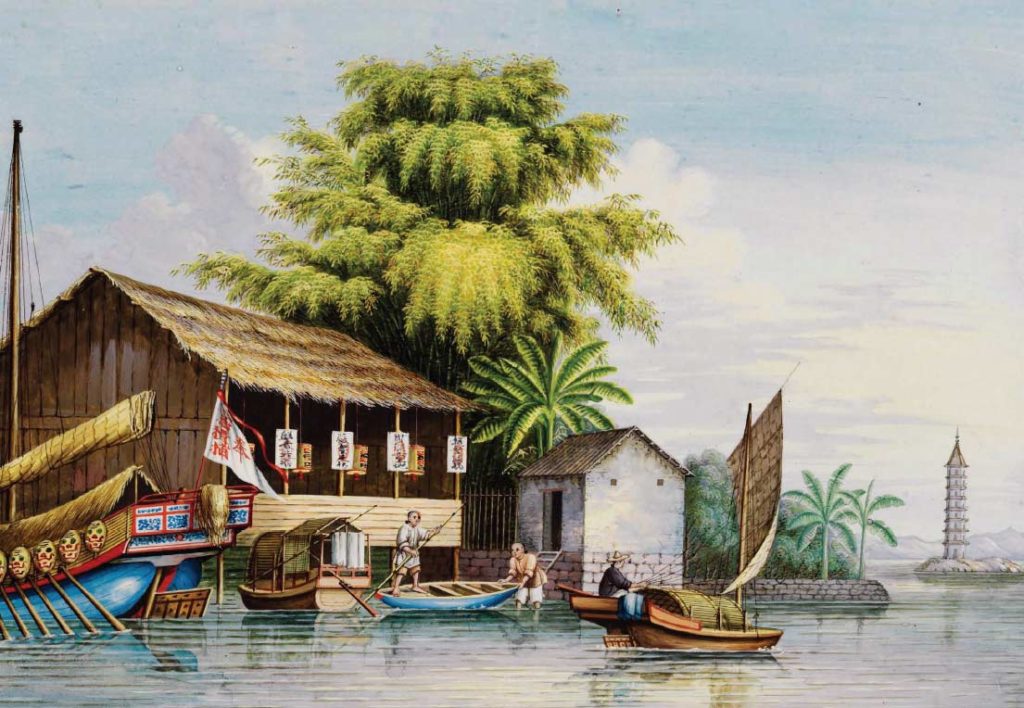

The Chinese way of presenting detail was pleasing and appreciated by Western clientele, one of whom commented: ” … we do not look for the higher excellences of the art, but are content if they exhibit splendid colours and great minuteness of detail”.8 In examples such as River Scene with Tea House, Near Guangzhou (10), this appreciation is convincingly accentuated in the fine and dexterous strokes on the bamboo leaves. Such features are stylistic characteristics, developed over decades, targeting the Western taste for Chinese art—not necessarily authentically Chinese, but nonetheless attractive in the eyes of the buyers of these works.

Once we understand the appeal of fineness and detail, a new arena opens up. For instance, it is noticeable how details in the paintings are being meticulously rendered, and the smallest detail offers significant information and meaning. The minuteness, and the sometimes hybrid sometimes Chinese perspective, in the Chinese Export works direct us to another major discovery that fundamentally changes how we look at, and value, export paintings by Chinese artists, at least the port scenes.

In the past, these works have long been considered quick commercial copies of each other, generally classified as careless souvenir art. This outlook partially explains why scholars have set aside the dating of some scenes when discrepancies appear. It is true that export paintings do look almost identical and were governed by a tight, conventional, compositional vocabulary. They were certainly based on a stereotyped visual formula, which made them look alike. However, in the course of research on the dating of works from the late 18th century to 1822, collaborating with Paul A. Van Dyke,9 we found that every single one of the approximately seventy scenes examined is different. 10 The changes are slight, and often hard to detect, because everything was so finely painted, but the differences are in the details: these were altered year by year, month by month, depending on the date they were painted.

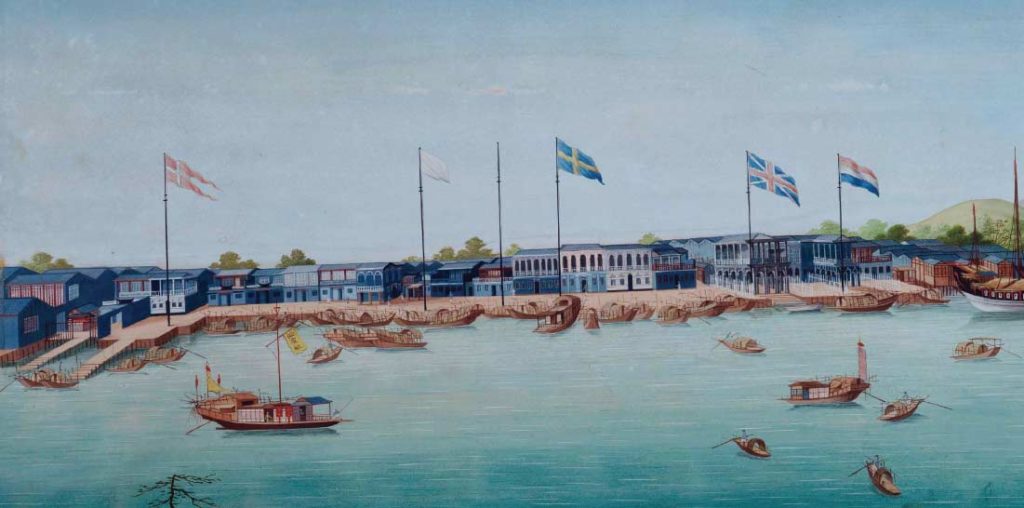

Our research focused on paintings with the hongs, or the temporary residences of the foreign traders at Canton, as subject matter. These hong paintings show that details matter, and when matched with historical records, most of the hong paintings from 1760 to 1822 are accurate and reliable representations. They match very closely with the written records, and also demonstrate that the demand side of the market very much dictated the extent to which Chinese artists held to accuracy. Buyers tended to prefer paintings with architecture and flags that were accurate for the period. New data on the hongs make it possible to show how correct the details in these paintings actually were. In some cases, it is possible to date them not only to a specific year, but to a specific month or week. The gouache in (11) is one such example.

A close-up of the hongs on the left side of the canvas (12) shows arched trimming on the lower levels of the British and Dutch verandahs, which does not appear in works dated after late October 1782. The French moved into the hong behind their Pre-Revolution white flag sometime in late October 1782. A flagstaff in between the French flag and the Swedish flag was for the Imperial flag, which is missing here. In 1782, John Reid, a Scottish private trader, was representing the Imperial Company, or Société impériale asiatique de Trieste et Anvers (1775–1785). Reid made arrangements to rent the old French factory (the hong behind that flagstaff). The Imperial Company flag was raised on November 17th, 1782. The only possible date for this work is a narrow window from late October to early November 1782, which explains the missing flag and the other details. In paintings with details that resemble those in (12), such as the artworks of 1783, the Imperialists arrived ahead of the French that year and the scene would have had both flags displayed.11

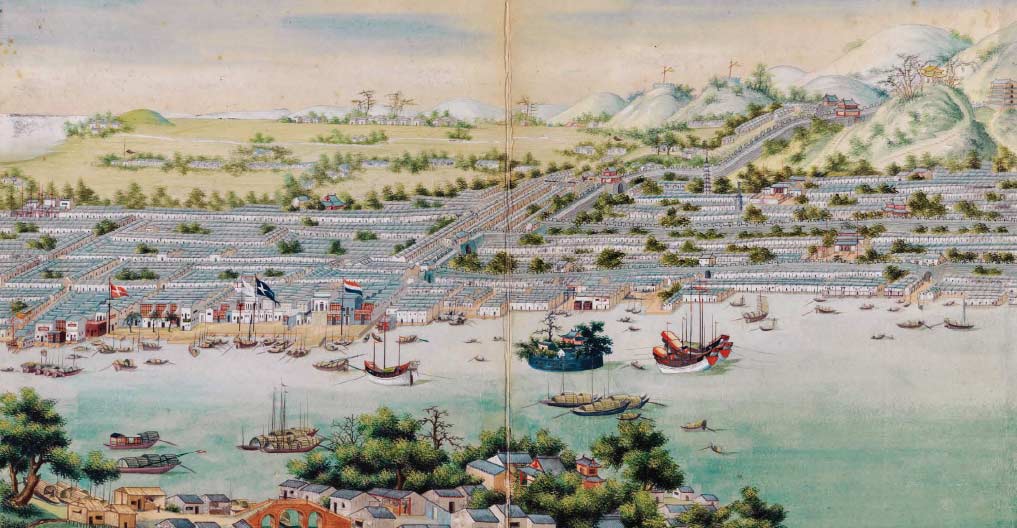

This echoes, and tallies with, our observations regarding the differences between the Chinese and the Western artists. Hong scenes by Western artists often show their concerns with aesthetic effects rather than accuracy. When their hong scenes are compared with those by a Chinese artist, we find them less focused on detail and more concerned with the overall pictorial effect. For example, a more realistic and natural viewpoint is exemplified in the splendid oil painting illustrated in (13). The artist, William Daniell (1769–1837), travelled to Canton in 1785 and 1793. Unlike Chinese export artists, Daniell’s work takes an oblique wide angle, showing more depth and three-dimensionality. The vantage point is taken from the far eastern end of the hongs, to the east of the Dutch factory, seen on the right side of the canvas. The artist seems to be preoccupied with these hongs on the east of the quay, which is not surprising given that Daniell was British. He would naturally have been much more interested in his own nation’s representation, i.e. the British factory at centre. The visual effect, that highlights his focus on that particular factory, was his mission, not the depiction of minutiae. Consequentially, all the flags are distorted in position, being pushed to the left of their respective buildings. Some of the hongs on the left, or the far west end of the quay are not clearly drawn. The omission of important details on the architecture and the flags make a precise dating impossible, unlike Chinese port scenes of the same period in the late 18th century.

Hong paintings by Chinese export artists are, therefore, most noteworthy from a historian’s perspective, as they embody the minutiae, accuracy and historical concurrency, that were unparalleled in other export art forms. For generations, export artists worked with astonishing fineness in all kinds of export painting. In order to retain the details and ensure consistency, Western precepts and conventions, that might affect accuracy, were dismissed or only partially adopted, to ensure a detailed, concurrent and accurate pictorial record. Multiple perspectives were used in some paintings, which essentially invited the viewer to examine the scene inch by inch, close-up and in full detail. They resorted to Chinese rules in order to fulfil those goals, but were again making a hybrid, to retain the details.

Mistakes Reconsidered

Recent research, thus, shows how these paintings were not reckless second-rate works, but were executed with the utmost care and strenuous attention to detail. They were so thoroughly executed that, in some cases, a flagstaff was not omitted when the flag was not raised. An empty flagstaff provides a meaningful record and was not an error. Hence, our research focus turned towards those “mistakes” or doubtful details, formerly thought of as a norm in China Trade paintings by Chinese artists.

In 2017, the findings of a second look at the “mistakes” in China Export art were also published.12 This study revealed that some of the most apparent errors in these paintings were not what we had believed. By examining a recent acquisition (14) with the above new mindset, we discovered that the problematic composition and landmarks are not careless mistakes, rather, they reconfirm that Chinese export artists were consulting other pictorial references and, very likely, conducting onsite observations: neither of these notions had previously been envisaged. To resort to a map suggests the difficulty the artist faced in order to achieve accuracy while trying out a more challenging perspective without aviation technology. The newly discovered vantage point from the west not only suggests onsite observation, it also reveals how seriously the artists worked, and how we have taken these problems in Chinese Export paintings for granted. By learning more about the creative and the production processes of Chinese Export painting, these “errors” have proven to be more meaningful than they might seem. Combining this knowledge with an extended study in 2018 on the market mechanisms, the successful role of the shopkeepers, and how the shops operated in Canton,13 it is even more apparent that substandard works would not survive in that highly competitive market. This, again, consolidates a new interpretation of the significance and historical meaning in export port scenes and their details.

While this concludes the scope and the fruits of our study of China Trade paintings at the HKMoA over the last decade, it is definitely not the end to our quest. It is the beginning of an entirely new way of looking at the history of Canton and paintings of the China Trade. New possibilities to re-examine the historical value of these scenes have been unveiled. These paintings can now be seen as reliable sources that augment textual records. When the written records fail to safeguard history, we can count on the pictures to inform. They will serve to spur further research, or provide pointers that initiate a revisiting of preceding knowledge. Since its temporary closure for renovation, the HKMoA has mostly shared the fruits of this research in publications. The next task will be to use these materials in exhibitions and programmes after the museum reopens in late 2019.

Bibliography

Crossman, Carl L., The China Trade: Export Paintings, Furniture, Silver and Other Objects, Princeton: Pyne Press, 1972.

Downing, C. Toogood, The Fan-Qui in China in 1836–7, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1838.

La Vollée, M., “L’Artiste. Revue de Paris”, The Bulletin of the American Art Union, 1850, pp. 118–119.

Mok, Maria Kar-wing, “Trading with Traders—The Wonders of Cantonese Shopkeepers”, in The Private Side of the Canton Trade, 1700–1840: Beyond the Companies, eds, Paul A. Van Dyke and Susan E. Schopp, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2018, pp. 64–84.

Mok, Maria Kar-wing, “Excellent Errors—Breakthrough Research into China Trade Paintings in the Hong Kong Museum of Art”, Hong Kong Museum Journal, Vol. 1, 2017, pp. 6–19.

Mok, Maria Kar-wing, “Mistakes or Marketing? Western Responses to the Hybrid Style of Chinese Export Painting”, in The Reception of Chinese Art Across Cultures, ed., Michelle Ying-ling Huang, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014, pp. 23–43.

Mok, Maria Kar-wing, “Waixiao huajia dui xifang jifa de renzhi—Yi Xianggang Yishuguan guancang wei li” (外銷畫家對西方技法的認知—以香港藝術館館藏為例 How Western Techniques Were Used in Chinese Export Painting—A Study Based on the Hong Kong Museum of Art Collection), in Lingnan huapai zai Shanghai—Guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji (嶺南畫派在上海—國際學術研討會論文集 Lingnan School of Painting in Shanghai—International Conference Anthology), ed., Memorial Hall of Lingnan School of Painting, Guangzhou: Lingnan Fine Arts Publishing House, 2013, pp. 260–275.

Van Dyke, Paul A. and Maria Kar-wing Mok, Images of the Canton Factories 1760–1822: Reading History in Art, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015.

1 Carl Crossman first brought attention to a description of this method used in the workshop at the studio of Lamqua, one of the most famous Chinese Trade painters: “The design is usually limited to a mechanical tracing made very easy by the extreme transparency of the paper. Each artist has a collection of printed outlines and from them he chooses at will the elements of each composition; a boat, a mandarin, a bird, anything that pleases him.” See Carl L. Crossman, The China Trade: Export Paintings, Furniture, Silver and Other Objects, Princeton: Pyne Press, 1972, p. 104. (However, this description is quoted from “Old Nick” by Paul Emile Daurand Forgues in La Chîne Ouverte, Paris: H. Fournier, 1845, p. 58, a work of fiction seemingly based on an account of Canton by an anonymous visitor.)

2 M. La Vollée, “L’Artiste. Revue de Paris”, The Bulletin of the American Art Union, 1850, p. 119; C. Toogood Downing, The Fan-qui in China in 1836–1837, London: Henry Colburn, 1838, Vol. II, p. 98.

3 Hong Kong Museum of Art, Artistic Inclusion of the East and West: Apprentice to Master, Hong Kong: Leisure and Cultural Services Department, 2011.

4 Maria Mok, <外銷畫家對西方技法的認知—以香港藝術館館藏為例> ( How Western Techniques were used in Chinese Export Painting—A Study based on the Hong Kong Museum of Art Collection), 嶺南畫派紀念館編:《嶺南畫派在上海—國際學術研究會論文集》(Lingnan School of Painting in Shanghai — International Conference Anthology) 廣州:嶺南美術出版社, 2013, pp.260–275.

5 Barthelemy Lauvergne was a draughtsman on the French ship, Bonite, which sailed around the world in 1836–1837, visiting South America, Hawaii, China, the Philippines and Calcutta (Kolkata).

6 The most important piece of evidence regarding Lamqua’s age is in the Hong Kong Museum of Art. It is an inscription on the back of the frame of an oil painting titled Self Portrait of Lamqua (accession no. AH1972.0010) that reads: “Lamqua/Aged 52/Painted by himself/Canton 1853” (dated 1854 in Chinese, a discrepancy awaiting further research). The date of Lamqua’s death remains a mystery, but literary accounts seem to suggest that he was no longer in business by the 1860s.

7 See Maria Kar-wing Mok, “Mistakes or Marketing? Western Responses to the Hybrid Style of Chinese Export Painting”, in The Reception of Chinese Art Across Cultures, ed., Michelle Ying-ling Huang, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2014, pp. 23-43.

8 C. Toogood Downing, The Fan-Qui in China in 1836-7, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1838, p. 103

9 Paul A. Van Dyke is professor of history at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou and an expert on the Canton Trade.

10 See Paul A. Van Dyke and Maria Kar-wing Mok, Images of the Canton Factories 1760-1822, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015.

11 For detailed analysis, see Van Dyke and Mok, 2015, pp. 32-33, and plate P21.

12 Maria Kar-wing Mok, “Excellent Errors—Breakthrough Research into China Trade Paintings in the Hong Kong Museum of Art”, Hong Kong Museum Journal, Vol. 1, 2017, pp. 6-19.

13 Maria Kar-wing Mok, “Trading with Traders—The Wonders of Cantonese Shopkeepers”, in The Private Side of the Canton Trade 1700–1840: Beyond the Companies, eds, Paul A. Van Dyke and Susan E. Schopp, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2018, pp. 64-84.

Subscribe

Subscribe Calendar

Calendar Links

Links Gift

Gift